Robots and AI-powered assistive tech are poised to transform accessibility and mobility

The first time Esther Klang tried the Atalante X, a self-balancing robotic exoskeleton, she was elated.

Klang, who is quadriplegic, works with Fable, an accessibility-testing platform that pairs product developers and people with disabilities who test and give feedback on assistive technology.

At first, Klang was skeptical. It took a few minutes for physical therapists to strap her into the exoskeleton. “It empowered me to stand up and walk independently for the first time in 18 years,” she told B-17. She credited assistive technologies more broadly with saving her from “desperation and extremely dark thoughts.”

The Atalante X is made by Wandercraft, a company founded by a group of engineers in 2012 that develops mobility technologies. The exoskeleton recently gained attention when Kevin Piette, a Paralympic athlete, wore it to carry the Olympic torch.

Kevin Piette, a Paralympic tennis player, carried the Olympic torch in the Atalante X, Wandercraft’s robotic exoskeleton.

The Atalante X is one of many game-changing developments in assistive technologies, a market predicted to exceed $12 billion by the end of 2036. Innovations like AI-powered or robotic mobility aids and communication tools are poised to transform everyday life for millions of people. But widespread adoption hinges on ensuring that the tech is affordable and reaches the people who need it.

Advancing rehabilitation

Dr. Laurent Metz, Wandercraft’s global chief medical officer, described the Atalante X as a “walking robot full of sensors.” The exoskeleton uses AI to predict which motions are needed to keep the user upright and moving, translating these into commands that are sent to a series of motors. “It’s an interactive process that’s repeated a thousand times a second,” Metz said.

This process takes place in rehabilitation hospitals and walking centers across the US, Europe, and Brazil under the guidance of medical professionals. One rehabilitation center said it conducted 750 sessions with more than 60 patients in just over nine months and that its patients had taken more than a million steps in the Atalante X.

Wandercraft is preparing to move out of hospitals and launch a personal exoskeleton. While the company hasn’t provided a timeline for the tech, its work is part of efforts to expand the availability and capabilities of assistive technology.

ReWalk Robotics has also been modifying an at-home exoskeleton to help users mount stairs and curbs. The exoskeleton was approved for personal use in 2014, but until recently it could be used only on flat ground. ReWalk says the modifications are designed to make more daily environments and activities accessible to people with spinal-cord injuries.

Assistive tech for everyday use

Accessibility technologies are already being used in homes nationwide. “You probably don’t think of a Roomba vacuum cleaner as an assistive technology, but it is,” said Elaine Schaertl Short, an assistant professor of computer science at Tufts University.

While the tech can be a quick fix for people who don’t have time to vacuum, Short said, it also aids those with physical challenges. “I also have a mobility impairment, so vacuuming isn’t the best use of my energy — I have this robot do it for me,” she said.

Other assistive technologies are redefining accessibility and mobility. For example, the Tatum T1, developed by Tatum Robotics, is a robotic hand designed to translate live voice and text output into American Sign Language. And Chronus Robotics has developed Kim-e, what it calls a hands-free “invisible wheelchair” with an adjustable seat that can be raised to standing height.

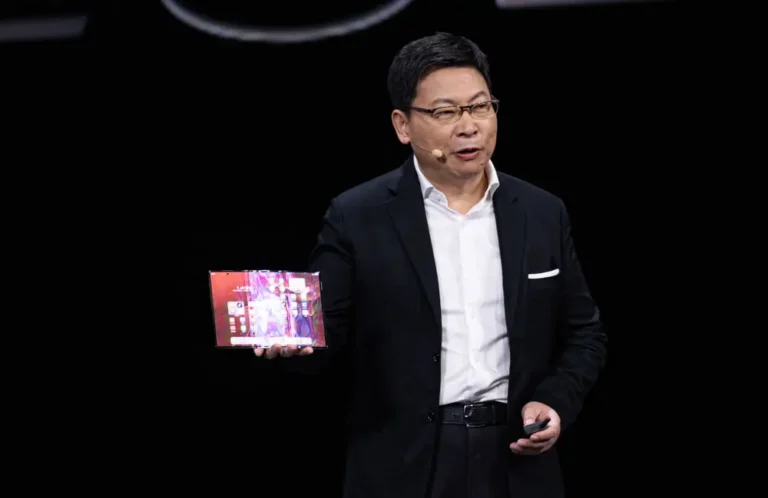

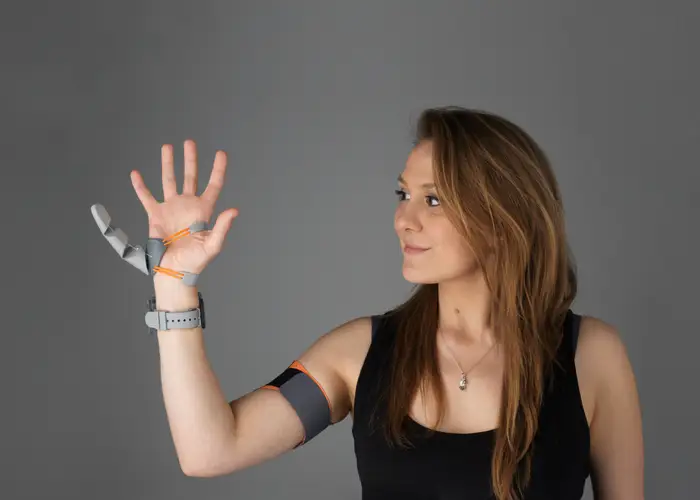

Robotics are also advancing the capabilities of prosthetic limbs. Dani Clode, an augmentation designer based in the UK, has worked alongside neuroscientists for several years to create and fine-tune the Third Thumb, which she describes as a “flexible, 3D printed thumb extension for the hand.”

The Third Thumb is a thumb-extension device.

Clode said developing the Third Thumb was a trial-and-error process, involving “several iterations and prototypes, refining both the mechanical design and the wireless control system.” The tech was the result of Clode’s quest to “design something that could be an extension of the body, accessible to everyone.”

The road to accessibility

While there are small-scale examples of assistive robots offering help in the house, technologies like robotic exoskeletons, limbs, and guide dogs have a long way to go before they become widespread.

In the meantime, researchers like Short and product testers like Klang work alongside engineers to ensure that marginalized people are factored into the development process.

Klang said it’s crucial that product-development teams “listen to and incorporate the insights of people with disabilities” as early in the process as possible. “We know what works for us and what doesn’t,” she added, describing it as “deeply frustrating” when products claim to be accessible but fall short.

Assistive technologies can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. That’s a problem for many Americans with disabilities, whom the National Disability Institute has found are more likely than their able-bodied counterparts to live below the poverty line.

Short said she’s confident that prices will decrease. Fifteen years ago, assistive robots like the PR2, which is no longer available, cost about $400,000. Now, similar tech — such as the Stretch 3 by Hello Robot — is available online for $25,000. “It’s still not accessible to most people,” she said, “but it’s an improvement.”

Still, Short told B-17 she considers most robots to be decades away from reaching the American home.

Short said she urges tech developers to consider “nonnormative users,” or people who aren’t able-bodied. Short pointed to the cellphone as an example of how technology can evolve to serve a wider range of users. “This is an incredible piece of assistive technology, but it wasn’t invented for disabled people,” she said. “There was a lot of catch-up work that had to happen on accessibility, but that work transformed a cellphone into something that could be used as assistive technology.”

While accessibility improvements take time, they can result in meaningful progress. Klang said her experience with the Atalante X has been life-changing.

Klang credits assistive technologies with enabling her to walk independently, adding that her work as an advocate and consultant for disabled communities feels life-affirming.

“I’m filled with anticipation for the continuous and rapid advancements in the assistive technologies which have significantly enriched my life,” Klang said.