Rom-coms like ‘Hot Frosty’ and ‘Notting Hill’ understand a key ingredient for love: walkable towns and cities

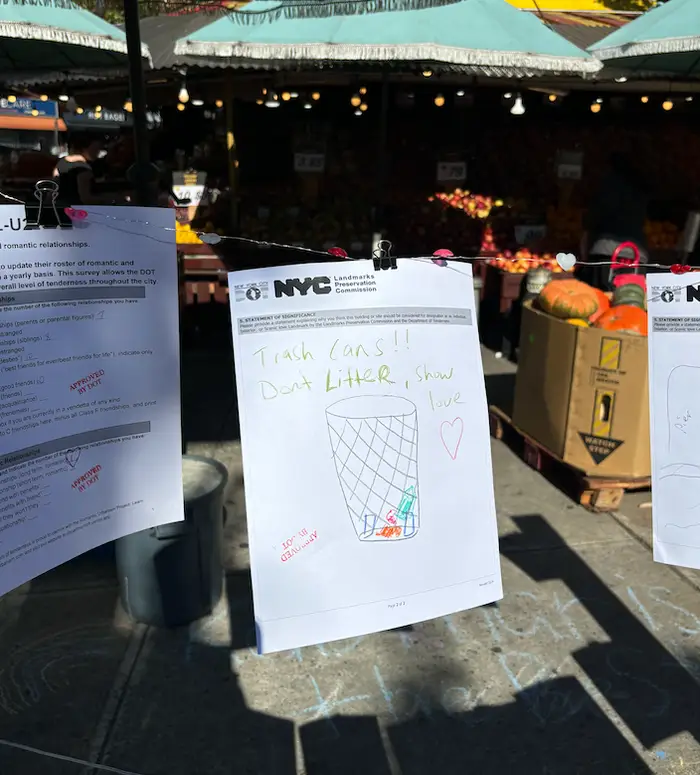

An event in Brooklyn featuring a tongue-in-cheek proposal for a New York City “Department of Tenderness.”

Netflix’s latest holiday rom-com, “Hot Frosty,” begins like this: A lonely young widow named Kathy hangs a magical scarf on a snowman in the public square of her idyllic fictional New York town. The snowman comes to life and happens to have a flowing head of hair and a chiseled physique, and is named, you guessed it, Jack. He and Kathy promptly engage in heart-warming hijinks and fall in love.

While the film gets originality points for romanticizing a snowman, it follows the classic holiday rom-com movie formula, which includes, as Bloomberg’s Linda Poon has written, an adorable, walkable small town. The town center is the picture of a “5-minute city,” with daily amenities clustered together, and plays a key role in facilitating Kathy and Jack’s romance. Without it, Kathy never would have stumbled upon Jack in snow form.

The crucial role that well-designed urban environments play in rom-coms struck Daphne Lundi and Louise Yeung — New York City urban planners and neighbors — when they spent the early days of the pandemic lockdown watching movies in each other’s apartments.

In the wake of the pandemic — that trapped many in their homes and ushered in widespread remote work and skyrocketing housing costs — urbanists like Lundi and Yeung are increasingly urging policymakers to counteract isolation through design.

Sparks flew in “third places” like art galleries and parks in “Rye Lane” and at urban landmarks like the Empire State Building in “Sleepless in Seattle.” Paris is a character of its own in “Amelie,” and the titular small town is a star of “Fire Island,” they noticed.

Harry wouldn’t have met Sally without a Manhattan bookstore. In “Notting Hill,” the London neighborhood is a central character in the romance between a famous Hollywood actor and a bookshop owner. In some cases — think “Sex and the City” and “Emily in Paris” — the characters are in love with the city itself.

Lundi and Yeung realized that in those romantic fantasies, a walkable urban landscape brings people together who might not otherwise cross paths — and lets them linger. They took that as motivation for how to make real-life cities and towns better for lovers or anyone looking to make new connections.

Lundi and Yeung first wrote about their theory in a 2023 essay called “Romantic Urbanism.” But the essay has since transformed into something bigger — a call for submissions including design proposals and public events. As policymakers, they’re tasked with building affordable housing, creating safe public spaces and accessible transit, and creating jobs. But despite their centrality to quality of life, love, intimacy, and connection aren’t policy goals, Yeung told B-17.

So they’re asking: “How can cities actually be designed to express care, to foster care? What does that care infrastructure actually look like in practice?” she said.

“We need to make spaces for people to be incentivized and for people to want to go out and hang out with each other,” said Clio Andris, a professor of city and regional planning and interactive computing at Georgia Tech who’s studied how urban design impacts romantic relationships.

A City ‘Department of Tenderness’

On a warm, perfectly sunny day in late October, Lundi and Yeung hosted their first public event showcasing their ideas for a more romance-friendly city — the inaugural meeting of what they’re cheekily calling the New York City Department of Tenderness — on a small car-free plaza in Brooklyn.

The event featured several proposals from Schuyler deVos, a creative technologist and web developer, including a presentation on a Brooklyn-Queens train line called the “V line” (Valentine’s line) designed to help those in “long-distance” inter-borough relationships.

The “Department of Tenderness” street signs direct people to mingle at stoplights and yield to families.

Henry McKenzie, who stopped by the presentation, said a cross-borough train line spoke to him.

“Every time you’re on the train for more than an hour to see someone, that is an expression of love,” he said. He’d also like more free or affordable third spaces where he could gather with his Dungeons & Dragons group, whose members are scattered across the city.

Trey Shaffer, a 25-year-old computer programmer from Long Island City who volunteered at the event, said he finds the pedestrian walkways on New York’s bridges to be especially romantic places. “We need more Brooklyn Bridges,” he said. “We can just make a copy, like, right next to it.”

One attendee at a “romantic urbanism” event in Brooklyn suggested cleaner public spaces will promote human connection.

A city built for romance benefits all kinds of other relationships, too. Lively street corners, safe and accessible third spaces, and affordable housing help familial bonds, friendships, and even loose ties between neighbors and coworkers.

McKenzie’s friend Sarah Dolan said that she tends to socialize exclusively with people she already knows in part because of a dearth of communal spaces. “There’s not that many opportunities to meet new people, unless you really seek it out,” she said.

Lundi and Yeung say they were overwhelmed with the response they’ve gotten to the project, which has received about 80 submissions, including essays and event proposals. One person wrote about their experience developing relationships while riding New York’s paratransit service for people with disabilities. Another is exploring corner bodegas as “care infrastructure.”

They hope the project will inspire more urban planners and policymakers to consider fostering human connection and relationships as a core part of their work and make real-world cities more like those in the movies.

“There’s this trope of city people as being hardened and hard,” Lundi said. “As a New Yorker, part of what this has shown me is that we’re actually really tender.”