San Jose promised a blight strike force — but not a single inspection has occurred

The Focus Area Service Team was supposed to launch in August

This summer, it was billed as a crackdown on businesses and residents who have allowed trash, weeds, and graffiti to fester in San Jose’s commercial districts — a new pilot program inspired by years of frustration with public safety and unkempt buildings in the city’s downtown and beyond.

Rather than the current model, in which citations are issued primarily in response to resident complaints, a dedicated team of code enforcement officers would seek out blight and ding those responsible.

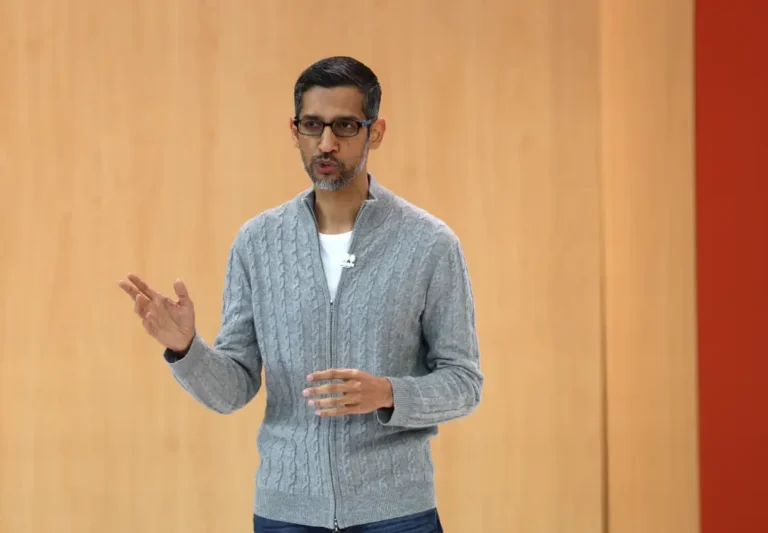

“This is really about accountability,” declared San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan at a news conference in June about the Focus Area Service Team, or FAST. “We’ve talked about getting back to basics a lot. Creating a city that is safer, cleaner, and (where) everyone has a place to live. And in order to get there, we must hold everyone accountable.”

Even the city itself, it turns out.

The Mercury News has learned that the launch of the coveted pilot program has been delayed for nearly two months, with inspections not expected to begin until at least November. The delay was discovered after this news organization requested data on FAST from the city’s code enforcement department on Wednesday.

RELATED: Who are San Jose’s worst blight offenders? A marijuana church and homes worth millions of dollars

“It’s taking a little longer than expected,” said Rachel Roberts, Deputy Director of Code Enforcement, in an interview. “This is primarily due to our staffing.” As you are aware, we have worked extremely hard to fill our vacancies. We’ve had to make some changes. As a result, I’m having to rearrange people. We didn’t make the changes as quickly as we had hoped.”

The postponement comes as blight becomes a top priority for the mayor and downtown residents, amid uncertainty about the city’s commercial vitality in the post-pandemic era. As of June, nearly one-third of available office space in the downtown core was vacant, a historic high.

According to Roberts, the program will have three code inspectors, one of whom will work part-time. The outreach to businesses and residents will begin in October, with inspections beginning the following month. These inspections, which will focus on downtown and commercial corridors in Districts 5, 6, and 10, will continue for the full six-month period. According to data presented by Roberts and the mayor in June, the vacancy rate in code enforcement has decreased from 28% in October 2021 to 4% in June.

“While we weren’t able to implement the inspections as quickly as we hoped, I’m confident that we’ll be able to effectively address blight,” Roberts stated. “Taking extra time to ensure that we do that correctly is really important.”

The city also has a significant backlog of code enforcement cases, with the city estimating 4,000 complaints in June. Around 300 of them were caused by blight. Code enforcement violations can range from illegal construction to the use of the incorrect materials for a residential retaining wall.

In August, Mahan and downtown Councilmember Omar Torres issued a strong condemnation to the owner of a property on East St. James Street that had been abandoned for years with a ripped-up plastic tarp covering the exterior of a church. Days after officials spoke out, construction executive Jim Salata sent a crew of workers on his own dime to remove the covering, prompting Torres to express trespassing concerns.

Salata called the FAST program’s delay “a crock of crap.”

“This is infuriating,” said Salata, the owner of Garden City Construction since 1988. “We’re not looking good. We must improve our performance. Code enforcement should be the first step.”

Torres has not responded to a request for comment.

This week, a review of San Jose’s top code enforcement offenders found nine properties, including a former marijuana church and two large estates, on the hook for a whopping $1.05 million in fines. None of the properties owed more than $100,000 are in the downtown core, and code enforcement has been at odds with some of the owners for nearly two decades.

Mayor Mahan, who began his tenure promising to carry through management themes learned in the private sector, said he’d like the city to “move faster” in light of FAST’s delay.

“I think that turnaround times in government are too slow,” he said in an interview. “I want us to be consistent in front of the public.” I want us to set and stick to deadlines. And I want us to move more quickly.”