Saudi Arabia’s Neom dreams are starting to crack under financial pressure

Saudi Arabia’s vision for its futuristic desert city, Neom, has always been the stuff of fantasy.

Touted as one of the most ambitious projects in the world, the megacity includes plans that could have been lifted from a sci-fi film. It features a high-tech linear city that will house more robots than people, a year-round ski resort featuring artificial snow, and theme parks that combine virtual and physical worlds.

When Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman first revealed the high-tech project in 2017, it was met with some skepticism. Since then, details about the project have been relatively scarce, with planners reportedly bound by strict non-disclosure agreements.

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Jeddah in March

But recently, a picture has emerged of a country beginning to feel the strain of its mighty ambitions.

“Neom was like was an imaginary city when it was announced,” Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, a fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, said. “Now, they’re finding it much more difficult to turn that imaginary vision into some sort of reality on the ground.”

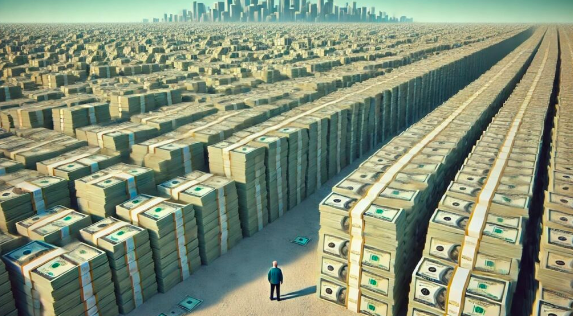

The main issue is the enormous cost of Neom. Saudi Arabia has struggled to attract the foreign investment needed for the megaproject, and experts say it’s not likely to secure it anytime soon.

Lack of foreign investment

The kingdom was counting on foreign investment to fund a large part of Neom, but things have not gone entirely to plan.

“When Vision 2030 was announced back in 2017, the assumption had been a lot of the funding would come in from foreign investment — that didn’t happen,” Ulrichsen said.

The drive for foreign cash hit an early stumbling block in 2017.

Just 10 days after the megacity was announced, 400 of the most prominent and influential Saudis were rounded up and detained in Riyadh’s Ritz-Carlton hotel, which had just hosted the Neom launch event.

The mass arrests spiraled into a full-blown purge and became the most contentious in the kingdom’s modern history.

“The hotel basically became a detention recap of the Saudi business elites who might have been expected to be the ones partnering with foreign investors,” Ulrichsen said. “Saudi foreign investment levels — they had been declining anyway — collapsed after this, and it’s been very difficult for them to build back up.”

In 2018, Saudi faced further global isolation after the brutal murder and dismemberment of dissident Jamal Khashoggi, a crime the CIA said was likely committed on Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s direct orders.

Jamal Khashoggi in London in September 2018.

“Generally, no one in the West wanted anything to do with the Saudis at this time, and investors pulled out in large numbers,” Andreas Krieg, a Gulf specialist at the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies at King’s College London, said.

Spiraling costs

The Saudi Public Investment Fund has propped up the lion’s share of the financial burden — but officials at the sovereign wealth fund are reportedly getting nervous about the spiraling costs.

The official estimate for Neom is $500 billion, but planners have dismissed the figure as unrealistically low. Other estimates have put the projected costs at as much as $1.5 trillion.

In April, Bloomberg reported that the financial realities of the country’s Vision 2030 plan, which includes Neom as its centerpiece, had started to cause concern within the government.

In February, Saudi also started borrowing to help fund some of the ambitious megaprojects.

In public, the Saudis have been keen to insist the project and funding are on track. In private, though, recent reports suggest that the Crown Prince is open to having “tough conversations” about the Vision 2030 ambitions.

Krieg said Saudi Arabia’s public spending bill was “extremely high,” raising questions about wasteful spending on megaprojects. “Vision 2030 consumes a lot of money, and there’s a lot of inefficiencies, especially when it comes to Western consultancy firms.”

Renewed scrutiny

In April, the kingdom once again became the subject of international scrutiny over alleged human rights abuses.

An explosive BBC News report claimed Saudi Arabia had authorized the use of “lethal force” to clear the way for Neom. The area was mostly populated by the Huwaitat tribe, which traditionally dwelled on areas earmarked for the megacity.

One of the villagers, Abdul Rahim al-Huwaiti, was later killed by Saudi authorities, according to Saudi activists.

In the wake of the report, human rights organizations began pressuring governments and businesses to act on the report — prompting at least one politician, UK deputy prime minister Oliver Dowden, to raise the allegations with the Saudi government.

Lina al-Hathloul, a human rights activist and head of monitoring and advocacy at human rights organization ALQST, told us that Neom was being “built on Saudi blood.”

“This project symbolizes the current state of the country: it was decided without the people’s consent, and when they oppose it, they are sanctioned in courts that lack independence,” she said.

The country has long tried to silence those who speak out against the project. Last summer, a Saudi woman was jailed for 30 years for criticizing Neom on Twitter.

“The reality behind such futuristic projects is the brutal repression of citizens and residents,” said Dana Ahmed, Amnesty International’s Middle East researcher.

“Businesses have a responsibility to conduct a thorough human rights risk assessment before operating in an environment that poses credible human rights risks, such as in Saudi Arabia.”

At least one company has withdrawn from Neom over human rights concerns. Malcolm Aw, CEO of Solar Water, previously told BI that he had pulled out of a $100 million Neom contract because of alleged Saudi human rights abuses.

Drawing The Line

There’s no doubt Saudi Arabia is barrelling ahead with The Line — the most prominent aspect of Neom.

According to executives, the number of people working on the project doubled in the past year. Satellite images provided to us also show the extent of construction underway at the site.

Construction work on The Line in Saudi Arabia.

Construction on the western end of The Line

But many questions remain about the project. Saudi Arabia has already reduced estimates for the number of people set to live in Neom by 2030, per Bloomberg.

According to Ulrichsen, many of the project’s lofty goals have always been “moving targets,” with several deadlines already pushed back.

As the Saudi government nervously eyes the ever-growing bill, Neom needs to generate enough excitement to attract foreign funds.

Despite the fresh scrutiny over human rights abuses, Krieg says that Saudi is now more palatable than ever on the international stage, and the outlook for the kingdom is positive.

Krieg said Neom’s very premise was built on levels of foreign investment that now seem unlikely to ever materialize. Meanwhile, competition from Saudi’s regional rivals such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi is heating up.

“There’s been some Chinese investments, but they are nowhere near where they need to be,” he said. “There’s always going to be a shortfall of foreign investment in Saudi to pay for all of these projects.”

Representatives for Neom did not respond to a request for comment.