Social Security promised a retirement free from poverty. Some boomers say it isn’t working anymore.

Millions of boomers without savings rely on Social Security in retirement.

Emma Echols has worked since she was 12 as a babysitter, chef, and convenience store manager.

The 68-year-old should be preparing for retirement, but she believes she’ll have to work for the rest of her life.

Echols lives in Alabama. She said she never made much money and has always lived frugally, but her rent and transportation alone cost her $1,000 monthly. She started taking Social Security early and receives $1,056 monthly — 25% less than she would have gotten had she waited until the federal retirement age of 67.

But she’s still working part-time as a bus driver making $26 per hour to pay the rest of her bills.

“I don’t see myself being able to retire, but I’m grateful and healthy,” she said.

She’s not alone: According to a NerdWallet study published last week of 2,100 adults, just 30% of respondents said they believe Social Security alone will allow them to live comfortably in retirement.

Over the past few months, B-17 has spoken with over 40 baby boomers and some Gen Xers, all of whom are struggling in retirement or fear they can’t retire because debt, low-paying jobs, and unexpected life circumstances have kept them from saving enough over the years. Though many say they are thankful to have Social Security payments at all, they aren’t enough to fill the gap.

Social Security is supposed to be American retirees’ safety net, but as it continually lands in political crosshairs, it might seem like a less safe bet than ever before. Full benefits are set to run out in 11 years unless Congress steps in with an infusion of funding.

“There’s just a lot of people who expect Social Security to be a really important piece to their post-work life,” Tracey Gronniger, managing director of economic security for the advocacy organization Justice in Aging, said.

Even with the current full benefits, some baby boomers are forced to continue working into their 70s and 80s, while retirees worry they may have to return to a part-time gig. Others said they’re considering moving out of the country for a lower cost of living or moving in with their children.

“At this point in my life, my expectations are very low,” said Cheryl Simmons, 62, who lives in her car in San Diego and makes $42,000 a year as a parking lot attendant — slightly too much to qualify for affordable housing. “I’ll have to work until I drop.”

Social Security varies by age and income, but the average monthly check is $1,907

Social Security, created in 1935, was implemented during the Great Depression to assist the more than half of Americans in poverty, including older workers looking to retire.

“There is no tragedy in growing old, but there is tragedy in growing old without means of support,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt said in a 1934 address.

Social Security benefits are based on a worker’s average monthly income during their 35 highest-earning years, adjusted for inflation.

For example, an American earning an average income of about $66,000 who retires at 65 will have 39% of that annual income replaced by Social Security, according to SSA estimates. This compares to an average income replacement rate of slightly over 50% in OECD countries — and nearly 80% in Spain and Greece.

Americans can begin claiming Social Security at age 62 — but their monthly amount is often higher if they wait longer to collect benefits. In 2024, the maximum monthly benefit is $3,822 for those claiming the benefit before turning 70; for those claiming the benefit at age 70, the maximum benefit is $4,873. However, the average monthly check is much lower: $1,907.

An annual income of just under $23,000 doesn’t go far in the US today. While Social Security was never meant to promise a life of luxury — and is ideally combined with savings and other investments — the baby boomers BI spoke to have struggled to save much at all because life events and low wages got in the way.

Some are part of the one in five older Americans who have no retirement savings at all. Experts say you can partially blame the US’ switch to 401(k) accounts from pensions in the 1980s, which largely replaced guaranteed retirement payouts funded by employers with investment plans that require employees to opt in and provide the bulk of their savings.

While many employers do offer 401(k) matches to their employees, the amount can vary greatly between companies. And, because participation and employer matches are voluntary — and income-based — this opt-in system can cut down on employees’ retirement savings and lead to even greater income inequality.

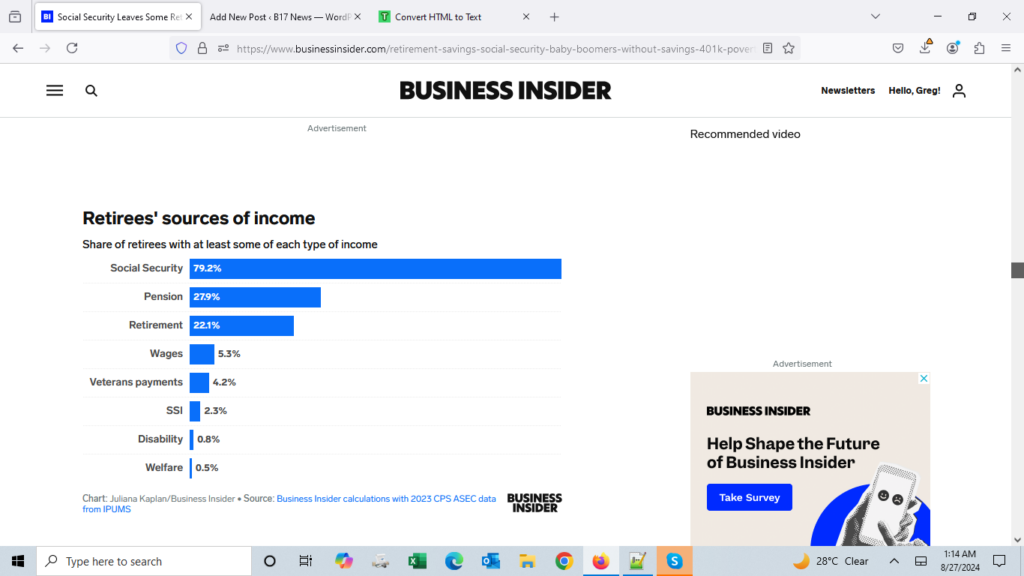

To help pay the bills, nearly 80% of retirees receive some Social Security income, per BI’s calculations, and the Social Security Administration estimates that 97% of older adults will ultimately receive benefits.

Retirees’ sources of income

Social Security indeed helps older Americans escape the technical definition of poverty. However, the official poverty line is based on a formula from the 1960s, a measurement that experts previously told BI is outdated and leaves many to fall through the cracks between needing help and making too much to qualify for assistance.

The baby boomers BI spoke with are not part of the group who have myriad investments, high-paying careers, or strong 401(k) employer matches. They are retired teachers, rideshare drivers, food service and retail workers; some live in a car or can’t afford groceries — and they certainly feel like they are living in poverty.

Others, however, have minimal expenses and live in low-cost-of-living areas, allowing them to live comfortably on Social Security alone.

Those who are already living check to check said they’ve been forced to drain savings accounts because their income isn’t enough to cover medical bills and unexpected expenses. And, with limited Social Security money, some boomers are forced to enroll in other government assistance programs like SNAP to put food on the table or return to work after retirement.

Mary Dacus, 62, and her husband Stephen, 67, live in Robinson, Illinois, on their combined $2,140 monthly Social Security income and $23 a month in SNAP. They’ve racked up thousands of dollars in credit card debt to pay for groceries, utilities, and healthcare. They feel like it’s their only way to survive.

“A lot of people think that, with Social Security, you get this big check, and you can move to Florida, and you could buy a boat and go fishing,” she said. “That’s not what it is.”

Becky Davenport, 61, works at a nonprofit outside Anchorage, a high-cost-of-living area. She told BI that her expected $2,000 monthly Social Security payments may not be enough. The single mom fears she may need to move in with her sons or find a roommate. Medical costs, housing expenses, and transportation have all chipped away at her savings.

“I usually had more money going out than coming in,” Davenport said. “I was kind of a master at juggling bills. I had some credit cards that I used for emergencies and ended up defaulting on all of those. I just managed to scratch out a living and keep a roof over my kids’ heads.”

Social Security solutions could include raising earnings caps and improving funding

With a presidential election coming up, Social Security is likely to be in the hot seat once again.

While Social Security is costly — it amounted to 21% of the federal budget in 2023 — it’s widely popular. Polling has consistently shown bipartisan support for the program; a Pew Research Center poll of 8,709 adults in April 2024 found that almost every group thinks Social Security benefits should not be reduced. That includes 77% of Republicans and 83% of Democrats.

Already, former president and current Republican nominee Donald Trump has proposed cutting taxes on benefits — a measure that an economist said could actually drain the program’s coffers faster.

Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, along with fellow Democrats, have proposed raising the earnings cap for Social Security taxes to offset hiking benefits by $2,400 a year. Currently, only income up to $168,600 is subject to Social Security tax, with income beyond that untaxed. On the other hand, some House Republicans have proposed hiking the eligibility age for the program.

Those proposals come against the backdrop of already-dwindling funding.

“We really want to see a more robust Social Security system,” Gronniger said. Already, she said, the program is lifting millions of adults out of poverty — but, with a very low poverty line in the US, that’s “not saying a ton.”

“We could do a lot more because I think what we want is for people to actually have real economic security and so feel as though they can afford the things not only that they need, but that people should have,” Gronniger said. “You shouldn’t be worrying about whether or not you can pay for all of your food and all of your medicine and all of your housing.”

But the dire straits older Americans have found themselves in, even with Social Security, point at a larger issue that might only get exacerbated: Retirement is becoming a luxury. As pensions dissipate and only higher-earning retirees have savings, Social Security might only become more pivotal for retirees. And that’s already not working so well.

“I don’t want to be rich, I just need to be comfortable,” 62-year-old Angela Babin — who lives on her $1,100 monthly Social Security check — told BI. “I just want to know that I can have food when I need it and a nice roof over my head.”

Are you living check to check on Social Security? Have you experienced loneliness because of your finances? If so, reach out to these reporters at allisonkelly@businessinsider.com, nsheidlower@businessinsider.com, and jkaplan@businessinsider.com.