The 1%Original data analysis shows it’s exceedingly rare for prisoners to win lawsuits claiming “cruel and unusual punishments.” Among the handful of large settlements, half involved prisoner deaths.

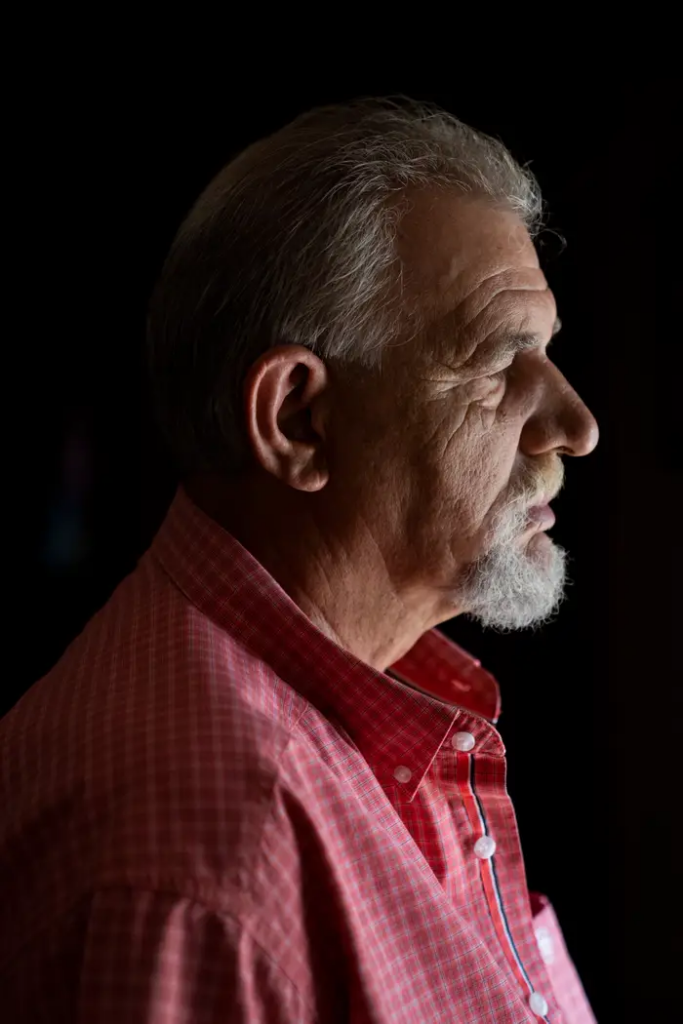

Christy and Darren Smith with a portrait of their late son, Joshua England, in front of their home in Fairview, Oklahoma. He died of a ruptured appendix while serving a one-year sentence at an Oklahoma prison called Joseph Harp.

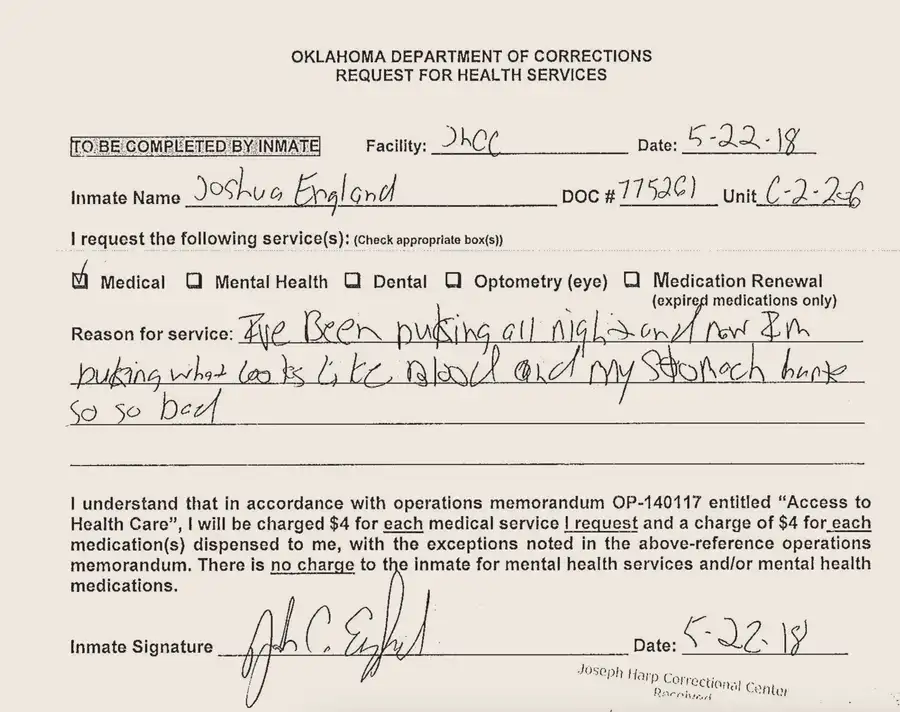

Over a span of days, Joshua England’s pleas for help became more desperate.

“I’ve been puking all night, and now I’m puking what looks like blood,” he wrote to his medical providers on May 22, 2018. “My stomach hurts so, so bad.” At the medical clinic that day he clutched his abdomen and described his pain as sharp and intense — an 8 out of 10. But he was seen by a lesser-trained licensed practical nurse, who didn’t give him a complete abdominal exam or send him for any lab work. Instead he was given Pepto-Bismol and told to drink water and eat fibrous food.

The Pepto-Bismol didn’t help. The next day England wrote that his pain was so bad he could barely breathe. He couldn’t eat or sleep. He again went to the clinic, where he said he’d had bloody stool and his pain was now a 10 out of 10. The physician assistant found that his pulse was racing but didn’t conduct an abdominal exam. Instead, he chalked up England’s symptoms to constipation and prescribed a laxative.

At that point someone with England’s symptoms might seek out a new clinic, to get a more thorough workup, or even head straight to an ER. But Joshua England didn’t have that option. He was inmate No. 775261 at Joseph Harp Correctional Center, a medium-security facility in central Oklahoma. He’d been sentenced to 343 days in prison after he and some buddies set some hay bales on fire one drunken night. This reconstruction of the events of those days in May 2018 is based on prison and medical records obtained by B-17 in collaboration with The Frontier, a nonprofit newsroom in Oklahoma.

In May 2018, England submitted a handwritten request for health services that described excruciating stomach pain.

Four days after he first requested help, England submitted his fourth sick call — a one-page form that prisoners at Joseph Harp used to request medical attention. He again wrote down how it was hard to breathe or even lie down. This time the licensed practical nurse who saw him consulted with the prison’s supervising physician, Robert Balogh. Balogh prescribed ibuprofen over the phone. He, and the physician assistant who saw England earlier, each had marks on their records: Balogh had been fined and put on probation for a time by the Oklahoma narcotics bureau, and the license of the PA had once been revoked for prescription fraud.

As medical professionals downplayed England’s symptoms, he continued to deteriorate. He couldn’t work or eat or shower; instead he remained in his cell, curled up on the floor in tears. Other prisoners reported that he had lost weight, his skin color had changed, and he no longer seemed fully cognizant.

On May 29, 2018, a corrections officer discovered England slumped over on the floor next to his cell. The Choctaw Nation kid who loved fishing and cattle ranching had died, just weeks after turning 21. Autopsy records show that the cause of death was a ruptured appendix.

Appendicitis is easily treated with minimally invasive outpatient surgery. Even treating a ruptured appendix is considered routine as long as the patient is immediately hospitalized. In this case, the PA was notified of his declining condition the morning of his death; he later told investigators he didn’t believe England’s condition had been life-threatening. A licensed practical nurse who saw England a few days earlier said she suspected he was in withdrawal and seeking painkillers.

The Smiths at home in Fairview. On May 29, 2018, a corrections officer discovered their son slumped over on the floor next to his cell. He had been complaining of acute pain for a week.

Five years after England’s death, the Oklahoma legislature approved a $1.05 million settlement with his mother, Christy Smith, to resolve a claim under the Eighth Amendment, which bars “cruel and unusual punishments.” During litigation, the Oklahoma attorney general maintained that the prison’s course of treatment was legitimate; in settling, the state admitted no wrongdoing.

Balogh, who no longer works for the department, confirmed the probation and said he was cleared to work without monitoring in 2015. He said he worked remotely for Joseph Harp so was reliant on information provided over the phone by the nurse, who he said did not mention that England had been having symptoms over a span of days. “You had a system where, many times, the physician was not there,” Balogh said. “There were some ways that information could fall through the cracks.”

A spokesperson for the Oklahoma Department of Corrections declined to comment about the case, as did Joan Kane, a clerk for the Western District Court of Oklahoma, on behalf of Judge Charles Goodwin, who presided. “It is atypical for federal judges to speak publicly about specific legal situations or cases,” she said. No other judge on a case mentioned in this story agreed to comment.

Few cases win outright

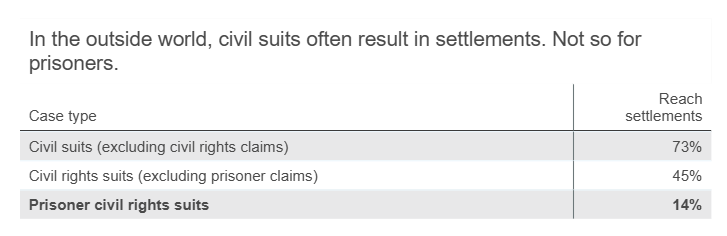

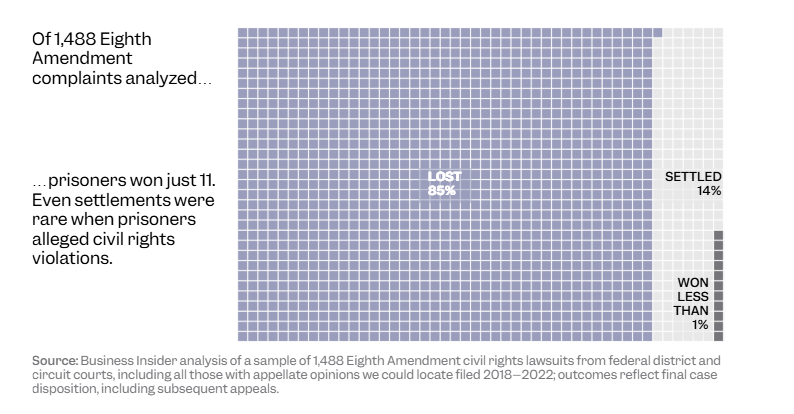

B-17 analyzed a sample of nearly 1,500 federal Eighth Amendment lawsuits — including every appeals court case with an opinion we could locate filed from 2018 to 2022 and citing the relevant precedent-setting Supreme Court cases and standards — and found that a settlement like Smith’s was exceedingly rare.

The cases in B-17 sample overwhelmingly detailed serious claims of harm, including sexual assault, retaliatory beatings, prolonged solitary confinement, and untreated cancers. Prisoners lost a vast majority of them — 85%.

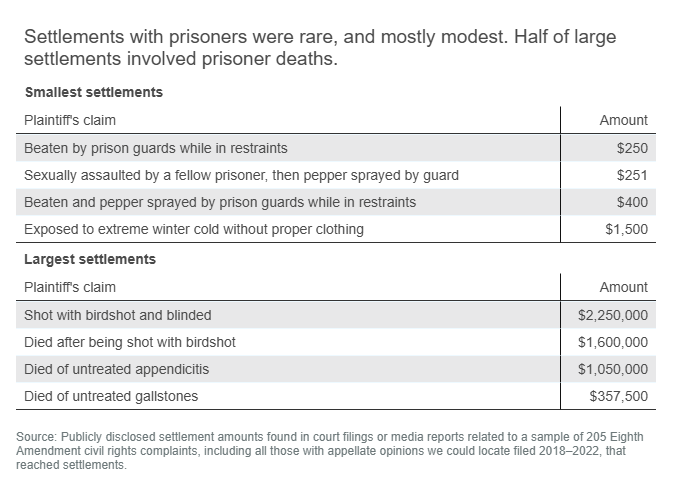

Roughly three-quarters of civil suits filed in the United States settle, and nearly half of nonprisoner civil-rights suits do. In B-17 sample of Eighth Amendment cases, just 14% settled. Many of the settlements were sealed. Of the rest, none involved an admission of wrongdoing by prison officials. B-17was able to identify just six cases that settled for $50,000 or more; half of those, including the England case, involved prisoner deaths.

Many of the cases settled for modest amounts: An Oregon prisoner received $251 over a claim that she was sexually assaulted by another prisoner and then pepper-sprayed by a guard. A Nevada prisoner got $400 on a claim that guards beat and pepper-sprayed him while he was in restraints. A New York prisoner won $2,000 for claims that he suffered debilitating pain while prison officials delayed treating his degenerative osteoarthritis.

In 11 cases — less than 1% of the sample — the plaintiffs won relief in court.

Seven of these plaintiffs won damages, the result of six jury trials and one default judgment; plaintiffs in the other four cases, including two class actions, were granted motions for injunctive relief, such as being freed from a prolonged stint in solitary. In one of these cases, a plaintiff in Wisconsin was granted access to gender-affirming surgery to treat her gender dysphoria after a seven-year delay. Along the way, the 7th Circuit granted the officials qualified immunity, which protects the conduct of public officials in the line of duty, so the plaintiff was denied damages. Beth Hardtke, the director of communications for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections, said the department updated its transgender-care policy in response to the ruling.

Litigants without lawyers

Another pattern jumped out: In every case in B-17 sample in which a prisoner prevailed, the plaintiff was represented by legal counsel. They were outliers.

In the vast majority of cases, 78%, prisoners litigated pro se — without counsel — in large part because a Clinton-era law, the Prison Litigation Reform Act, tightly capped attorney fees, making it prohibitive for lawyers to take prisoner cases. B-17 interviewed 10 attorneys who represented prisoners or their families in cases that prevailed; they all said the cases would have struggled to succeed without counsel.

“Pro se litigants do not win cases in federal court,” said Victor Glasberg, one of a team of attorneys who successfully proved in 2018 that conditions on Virginia’s death row violated prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights. “When faced with abysmal anti-plaintiff litigation and jurisprudence, the chance of a pro se litigant getting to first base is about as good as my flying to the moon.”

Even lawyers struggle to master the convoluted standards that now guide Eighth Amendment claims, said Chris Smith, a Mississippi attorney who won a constitutional claim over inadequate medical care in 2021.

as responsible for treatment delays.

But prisoners face a litany of hurdles, he said, starting with the difficulty they face obtaining records.

They don’t have experience in the rules of civil procedure, he said. They don’t know how to plan a litigation strategy, or draft jury instructions, or take depositions.

In England’s case, because he had died, his mother was the plaintiff in a 2019 lawsuit alleging that corrections and medical staff had failed to treat his appendicitis. Since she was not incarcerated, she was able to secure legal counsel free from the PLRA’s fee caps.

The settlement, reached after a four-year legal battle, did not require the defendants to admit to any wrongdoing. State taxpayers, rather than the named defendants, footed the bill.

“The people that actually were responsible for it,” England’s stepfather, Darren Smith, said, “have no accountability whatsoever.”

Prisoners succeed more before juries

“The people that actually were responsible for it,” Darren Smith said of his stepson’s death, “have no accountability whatsoever.

One federal judge, Lawrence Piersol of the South Dakota District Court, said that in his experience, jurors are not generally sympathetic to imprisoned plaintiffs. B-17 data indicates that plaintiffs actually fare somewhat better before juries than before judges. Of the 1,488 cases in B-17’s sample, prisoners prevailed more often before juries. Just 2% of the cases B-17 reviewed were decided by a jury. Yet more than half of the 11 prisoners who won their suits had jury trials.

Glasberg, the Virginia attorney, said he suspected that if more cases were decided by jurors, it would “significantly improve the plight of people in prisons and jails.” Many prisoners, he said, see their cases dismissed preemptively by a judge, before a jury has the chance to hear evidence.

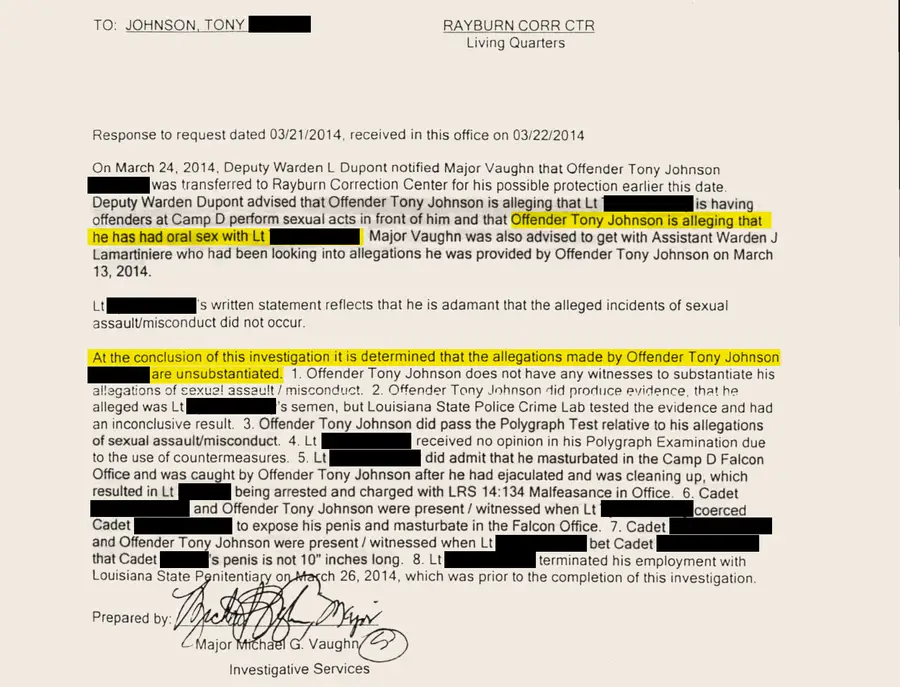

One Louisiana prisoner, Tony Johnson, was awarded $750,000 in 2020 after a jury found that a guard at Angola had sexually assaulted him. The guard denied the allegations.

Johnson’s lawyer, Joseph Long, told B-17 that the verdict was the result of years of litigation, including obtaining dozens of depositions and spending nearly $40,000 on the case. The underlying Eighth Amendment claim, he said, entailed abuse with the potential to infuriate even jurors sympathetic to law enforcement.

A Louisiana prison official responds to claims by a prisoner, Tony Johnson, that he was sexually abused by a corrections officer, saying an internal prison investigation found them “unsubstantiated.” Johnson won $750,000 after taking the case to trial.

“Prison isn’t supposed to be good, but when they get raped by a guard even the most hard-bitten conservative has to admit that’s wrong,” Long said. The guard resigned from the prison in 2014 and was never criminally charged; four years after the verdict, Long said, his client has yet to receive his money from the state. The Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections declined to comment on the record.

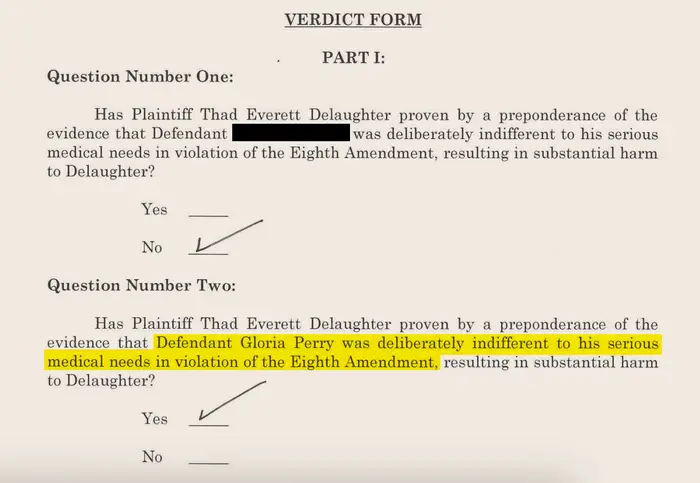

Chris Smith’s client, a Mississippi prisoner named Thad Delaughter, had complained for years about severe hip pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis. Eventually, in 2011, he was allowed to see an outside specialist who found that he needed surgery to reconstruct his hip. The operation was scheduled, only to be abruptly canceled; one of Smith’s arguments in court was that prison officials didn’t want to foot the substantial bill.

In a rare win for a prisoner plaintiff, jurors found that the chief medical officer for the Mississippi Department of Corrections had violated Thad Delaughter’s constitutional rights by failing to meet his medical needs

The treatment kept getting delayed as his condition deteriorated. At trial, jurors found that Gloria Perry, the department’s chief medical officer, had violated Delaughter’s constitutional rights by delaying the procedure; he was awarded $382,000 in damages and, in 2022, had the operation.

Perry denied any wrongdoing, saying in court filings that her actions didn’t rise to the level of a constitutional violation; her motion for a new trial was denied. A representative of the Mississippi Department of Corrections said Perry no longer worked for the department and declined to comment on litigation matters; her attorney did not respond to queries.

England, who loved fishing and cattle ranching, died just weeks after he turned 21.

‘I want him to live’

Among the jury wins for prisoners in B-17’s sample were two cases filed against doctors who worked for Wexford Health, the private correctional healthcare company. In one case, an Illinois prisoner named William Kent Dean convinced a jury that his kidney cancer had metastasized after healthcare providers failed to diagnose and adequately treat his symptoms over a span of seven months. At one point, email records showed, Wexford employees discussed admitting him into hospice in lieu of paying to treat his illness. “He’s the love of my life,” Dean’s wife, Cynthia Dean, said during the trial, “and I want him to live.”

In 2019, Dean won $11 million in damages at trial against Wexford and two of its medical providers. Appeals court judges of the 7th Circuit then sent the case back, after finding that Dean hadn’t proved the defendants were “deliberately indifferent” to his suffering, as the Supreme Court requires.

One 7th Circuit judge, Diane Wood, dissented, writing, “Wexford directly learned of the lack of significant medical intervention and the arc of Dean’s cancer’s progression, yet still did not act efficiently or effectively.”

Dean died of kidney cancer in 2022 at the age of 61.

Wexford and the Illinois Department of Corrections did not respond to requests for comment.

In August, a new jury again found in favor of Cynthia Dean, who had taken over as plaintiff. This time the award was $155,100. Wexford, in a court filing, denied all of the allegations.

B-17’s database is packed with cases that also allege significant harm — but the plaintiffs lost.

One was another Illinois prisoner under the care of Wexford, who sued his doctor for waiting over a year to test for an abdominal hernia — prolonging his pain and delaying corrective surgery. Another involved an Oklahoma man who filed suit saying that a prison doctor had improperly discontinued his medication to treat chronic nerve pain from tongue cancer. Both cases were dismissed when judges found the prisoners could not prove their doctors were deliberately indifferent.

A woman in California sued after doctors persistently misdiagnosed a growing lump that, years later, was diagnosed as Stage 4 breast cancer. Even then, she said, doctors denied and delayed chemotherapy as the cancer spread.

The US District Court for the Eastern District of California dismissed her case when she died. There was nobody to take over for her as plaintiff.

Terri Hardy, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, declined to comment on the breast cancer case and said the department works to ensure that its complaint process is fair, thorough, and timely. A spokesperson for the Oklahoma Department of Corrections declined to comment on the tongue cancer case.

England’s cowboy boots, leather belt, and dog-eared Bible.

Large settlements for prisoner deaths

One way for a plaintiff to win a large settlement, B-17 found, is to end up dead.

Of the six lawsuits B-17 identified that settled for $50,000 or more, half of those were filed by family members such as Josh England’s mother, Christy Smith, whose sons or brothers died behind bars. Unlike prisoner plaintiffs, these surviving relatives didn’t have to overcome the PLRA’s hurdles.

“Somebody has lost their life, so there should be a lot of money,” said Paola Armeni, a Las Vegas attorney. “They’re not getting their loved one back.”

Armeni’s case is one of a handful in our sample in which a lawsuit forced substantive change. She represented the family of Carlos Perez Jr., a Nevada prisoner who was killed in 2014 at Nevada’s High Desert State Prison by a trainee officer named Raynaldo-John Ruiz Ramos. Ramos shot Perez multiple times with birdshot, a kind of ammunition used to hunt small game. “They lit him up,” Armeni told B-17. “The birdshot was from his waist up. It was a murder.”

Six months later, a prisoner named Stacey Richards was permanently blinded when a corrections officer shot him with birdshot at another Nevada prison, Ely State.

After an eight-year legal battle, the state settled last year with Perez’s family for $1.6 million. That same year, a case filed by Richards settled for $2.25 million. In exchange, Richards’ attorney agreed that his client wouldn’t talk to the press about the case. Ramos maintained in court that firing his weapon was a reasonable use of force to break up a fight between prisoners.

As a result of Perez’s death, the state corrections commissioner was forced out and the department commissioned an external review of its use-of-force policies, ultimately agreeing, in 2015, to phase out the use of birdshot, which prison guards had deployed for decades.

In reaching a settlement with the Perez family, the state did not accept liability for Perez’s death, even though the Clark County coroner’s office had ruled it a homicide.

The Nevada Department of Corrections declined to comment; Ramos’ attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

Ramos was charged with involuntary manslaughter. In 2019, he entered a plea deal. In exchange for community service and a mental-health evaluation, he avoided prison.