The ‘Bachelor’ electionHow the reality TV show became the pivotal demographic in the 2024 election

Ben Higgins, 35, could be your prototypical politician.

Charming, handsome, and well spoken, Higgins uses his work as an entrepreneur and philanthropist to help fight poverty. He’s also an independent who doesn’t identify strongly with either side of the political spectrum.

“It’s very topic by topic for me,” he said. “It’s very much understanding the issue, hearing the story behind the issue, hearing why people believe what they believe, and then trying to make logical, rational solutions and decisions.”

If Higgins’ name sounds familiar, it’s probably because you saw him on television — and not during a debate. Higgins served as the 20th American Bachelor on ABC’s long-running and wildly popular romance reality show. Higgins did somewhat attempt to use “The Bachelor” as a jumping-off point into politics; back in 2016, he was given the opportunity to run for state representative in Colorado while working on his own spinoff show. But that bid was incredibly short-lived.

“That ran into issues over time, mostly legally, with how that was going to be filmed and who they were filming and how they were showing it. And that’s ultimately why my campaign had to end,” Higgins said — seemingly nodding to reports that the corporate overlords at Disney, which owns ABC, did not want to televise the former Bachelor’s political ambitions. (The Disney-owned channel set to air the spin-off said at the time it had concerns broadcasting a show featuring the campaign “could raise significant compliance issues under Colorado election laws.”)

Ben Higgins tried to parlay his Bachelor success into a political career, but the campaign didn’t last long.

Bachelor Nation’s aversion to comingling political ambitions with the TV show makes some sense. Popular culture has for years been breaking into niche after niche. You can exist in a bubble of “The Bear” watchers without ever joining the masses watching “Young Sheldon.” But “The Bachelor” is different: It’s perhaps one of our last monocultures, alongside stalwarts like the NFL. The show, which kicked off in 2002, has had its ratings stumbles over the years, but it has recently experienced a viewership resurgence, with just over 6.3 million people tuning in to watch the finale of Joey Graziadei’s season in March. “The Golden Bachelor,” which featured contestants over the age of 60, delivered blockbuster ratings in late 2023, reaching the coveted 18-to-49 market while courting older viewers. Given the franchise’s relatively strong position, why risk that power by mixing in the messy, polarizing, and exhausting world of American politics?

But under the surface, “The Bachelor” is already a political show. Whitewashed, vaguely Christian, and deeply heterosexual, the presentation of “The Bachelor” is a lot like the median US voter, which is also the exact audience it’s long catered to. Its fandom reaches across a wide spectrum of the population in a way few other forms of mass media do, and the show itself reflects many of the broad sociopolitical themes in America. So it might be worth accepting the rose and looking at what the show tells us about the country. By understanding “The Bachelor,” we can better understand the political landscape of America — and maybe even glean a little insight into this year’s election.

Who will win the 2024 rose?

Graziadei, the Bachelor who delivered monster ratings in the spring, made a cameo in February at a different kind of rose ceremony. Instead of looking for love on his own, Graziadei was helping the second gentleman, Doug Emhoff, present a rose to Vice President Kamala Harris in honor of Valentine’s Day. It was a moment that breached the fourth wall of “The Bachelor”: a lead openly acknowledging and becoming a part of politics. (The White House declined to comment on the collaboration.)

When Chad Kultgen and Lizzy Pace, the cohosts of the popular “Bachelor” podcast “Game of Roses” and coauthors of “How to Win The Bachelor,” saw the video of Graziadei at the White House, they were stunned. Their podcast examines the game mechanics of “The Bachelor” like a sport — akin to its fellow monoculture, the NFL — and goes in deep with statistical metrics to analyze contestants’ strategies and plays. Pace said she “screamed” when the video came out.

“I couldn’t believe what I was looking at,” she told us. Kultgen, for his part, theorized that it was orchestrated by Harris’ people — you wouldn’t see a producer or ABC reaching out to the White House for a collab.

“Whoever’s part of putting together their propaganda is saying: We need to get ‘The Bachelor’ in here,” Kultgen said of the strategy by the vice president’s team.

Joey Graziadei stepped out of “The Bachelor” and into a video with Vice President Kamala Harris.

Beyond the holiday-themed video, the Harris campaign’s desire to court Bachelor Nation was also made clear by a line tucked away in a recent press release about its big plan to spend $90 million in August on advertising.

“Ads will be targeted to high-impact programming that reaches the voters Team Harris-Walz needs to reach to win 270 electoral votes,” the press release said. “That includes local broadcast and cable programming and non-political programming like The Bachelorette, Big Brother, The Daily Show, Love & Hip Hop: Atlanta, and The Simpsons.”

During a political season that is awash in advertising, the campaign is sending a clear signal: The demographics it can reach during breaks from the rose ceremony could be key to swinging the election.

The focus on Bachelor Nation also makes sense given the franchise’s viewership is dominated by one of the most crucial swing votes of recent elections: white women. A 2020 study from the polling firm YouGov found that about three-quarters of “Bachelor” fans were women and that a similar share was white. The fandom is split between younger and older viewers; about one-third of viewers were between ages 25 and 44, while roughly one-quarter were 65 or older. In the past two presidential elections, white women were the most closely split demographic subgroup tracked by major exit polls. In 2016, Donald Trump won over 52% of white women against Hillary Clinton’s 43%, exit polls found, while Trump bested Joe Biden in 2020 among white women 55% to 44%. That relatively close divide is set to continue in 2024. In the Pew Research Center’s most recent national poll, conducted between August 6 and September 2, Trump led among white women with 54% of the vote to Harris’ 45%. As in the exit polls from the past two elections, that 9-point difference was the smallest among the race and gender groups studied in the poll.

The close divide is even more apparent in key swing states. A Quinnipiac swing-state poll conducted between September 4 and September 8 found a tight race between Trump and Harris in Georgia and North Carolina, and the cross-tabulations suggested that white women could be a deciding factor in each state. Trump had a strong 64% to 31% lead over Harris among white women in Georgia, but in North Carolina, Harris led among the demographic 51% to 47%. It shows how this group could decide the next election.

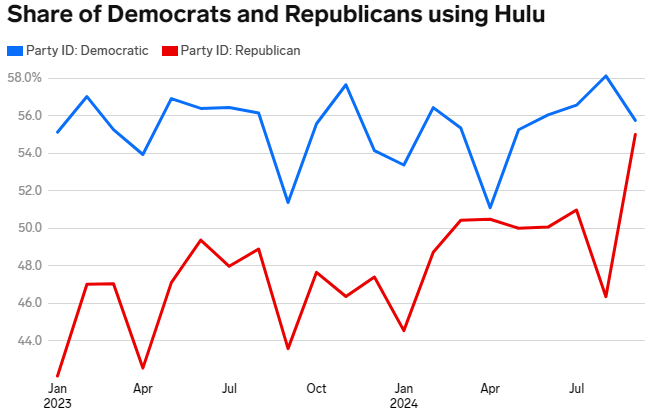

And rather than catering to one side of the political aisle or the other, Hulu, the platform that hosts “The Bachelor” for streaming, has robust bipartisan usage. In a Morning Consult Intelligence poll of 27,633 people from January 1, 2023, to September 9, 2024, about half of US adults said they used Hulu. As for the demographics of that usage, about 56% of Democrats and 55% of Republicans said they used Hulu — with Republicans in particular seeing a spike during the most recent season of “The Bachelorette.”

The overlap between the swingiest demographic and the “Bachelor” audience suggests Bachelor Nation has value to those who seek to lead our nation.

A tense history of race and religion

As much as “The Bachelor” can tell us about the state of the country’s politics, America’s shifting landscape has also been reflected back into the reality of the show. For most of its run, the show has operated within a certain framework: Politics are never overtly discussed, and neither are hot-button issues like abortion or guns. Things like a nonwhite lead or a predominantly nonwhite cast are still relatively new in the world of “The Bachelor.” It’s also rooted in an omnipresent but barely visible sense of Christianity. Contestants are assumed to be Christian until they’re not — but skew too evangelical, and you’re edited to look a little less religious.

“I actually find ‘The Bachelor’ to be very political. When I watch the show, it, to me — it is pretty obvious that it’s a conservative-leaning production,” Natasha Scott-Reichel, a cohost of the popular “Bachelor” and pop-culture podcast “2 Black Girls, 1 Rose,” said. While the show might be aiming to be apolitical, that’s a statement in and of itself.

“The void of diversity for so long is within itself a statement about its politics — that it is trying to cater to this Middle America that is very afraid of conversations, particularly surrounding race or sexual identity or sexual orientation,” Scott-Reichel said.

In the past few years, however, politics and the contestants’ political identities have begun to spill into the carefully maintained middle of the road. For the Americans who have seen their loved ones — or even themselves — galvanized out of political apathy in the wake of the 2016 and 2020 elections, it’s a transformation mirrored by their favorite reality show.

In 2018, Claire Fallon — a cohost of the popular “Bachelor” podcast “Love to See It” — accidentally helped kick off one of the first public cracks in the “Bachelor” veneer of apoliticism. Before the Bachelorette Becca Kufrin’s season even kicked off, Fallon and her cohost, Emma Gray, helped corroborate accounts that Garrett Yrigoyen, the eventual winner, had been liking posts from right-wing Instagram pages. Kufrin was a fairly public liberal, which turned the whole viewing experience from a fairytale love story into something much more realistically American: two people who were dating and did not realize they had drastically different political views. That moment was a pivotal tiptoe toward something new. Yrigoyen apologized for his likes and discussed how it strained him and Kufrin as a couple. But the conversation didn’t broach the substance of those likes. The couple split in 2020, and Kufrin later told B-17 that if she were to become the Bachelorette again, the first thing she’d do when she walked into the house would be to ask everyone whom they voted for.

”There’s no way in hell they’d show that conversation,” she said.

And while the fan base moved on to its next Bachelor — Colton Underwood, a former NFL player who later came out as gay and married a Democratic strategist — Fallon said politics started to become an active topic of discussion in the parasocial world of its loyal fan base. Higgins thinks the fascination with contestants’ politics and likes goes back to something at the core of the show: relatability (he believes this is why he was handed the lead role). People want to see themselves in contestants, and that includes some of their closest-held beliefs.

“I think people are still looking for that relatability, and so they’re intrigued with, ‘Well, I like you for what I see on television, but do I like you for actually what you stand for politically?'” Higgins said.

That was a moment where the political turmoil in our country created an internal conflict for the show that it couldn’t really resolve

The Kufrin-Yrigoyen situation was mostly quelled (or at least forgotten) in the court of public opinion, and as Fallon said, the show erected barriers against the rising tides of political polarization, working hard to keep itself out of it. But soon, the barriers were fully breached. The 25th season of “The Bachelor,” which aired in early 2021, featured the franchise’s first Black male lead, Matt James, who was 28 when the show was filming. Rachael Kirkconnell, the season’s eventual winner, caused a whirlwind of controversy when photos emerged on social media of the contestant attending an antebellum-plantation-themed party a few years prior. The reaction was furious. James’ and Kirkconnell’s finale, broadcast live after the pictures had come out, eschewed the traditional “Bachelor” ending of checking in on the happy couple in favor of a two-hour discussion on race in America. The franchise’s longtime host, Chris Harrison, was fired after defending Kirkconnell’s photos — even though she was on a tour apologizing for them. A franchise that had long aimed to sit in a happy apolitical parallel-universe America unburdened by the country’s often dark history was thrust onto one of the nation’s core cultural fault lines.

“That was a moment where the political turmoil in our country created an internal conflict for the show that it couldn’t really resolve,”

Fallon said. Since then, it’s been difficult for the show to avoid politics despite desperate attempts to steer away from them. And as Justine Kay, the other cohost of “2 Black Girls, 1 Rose,” noted, it took making a Black woman the Bachelorette — the well-regarded Charity Lawson — to lure audience members back to the show, which had been dealing with its own rating slump.

Since then, much like the rest of America’s interest in the daily machinations of Trump-run Washington, the fans’ fascination with the contestants’ politics hasn’t evaporated but seems to have become more tempered. After all, President Joe Biden’s tenure has often been deemed boring, marked instead by quieter policy work. In the same vein, over the past few seasons, prominent contestants have reportedly liked right-wing and Trump-leaning posts; those revelations haven’t seemed to rock the fan base as much as in the past.

“Partly what we’re seeing is that it feels like the battle for cultural dominance in the form of ‘Bachelor,’ within the franchise, is no longer a fever pitch,” Fallon said. “It feels like the liberal viewers sort of won.”

Kultgen tied that sentiment to the larger political landscape. During the Trump administration, right-wing posts and sentiments were not given an inch of space because every moment felt like a crisis. The “Bachelor” fan base’s newfound shrugging might reflect the cultural and political spotlight Trump has lost; he’s a candidate who can become effectively trolled over claims around how many people are showing up to watch him. In the past — like in 2018 — questioning Trump support was a brave new world for Bachelor Nation. Now it’s become almost the default. It’s ironic that the reality-TV-show candidate has lost the reality-TV viewers. Of course, that’s not to say that the “Bachelor” fan base, or contestant base, became leftist overnight. But the carving of centrist, left-leaning politics as the new base expectation is a development years in the making. This time, there was no larger-scale reckoning onstage with the ramifications of liking Trump; the show has done that, something that would’ve been unheard of a decade ago. And if that’s where the winds of the monoculture are blowing, the Harris-Walz campaign ad spend might be a good bet.