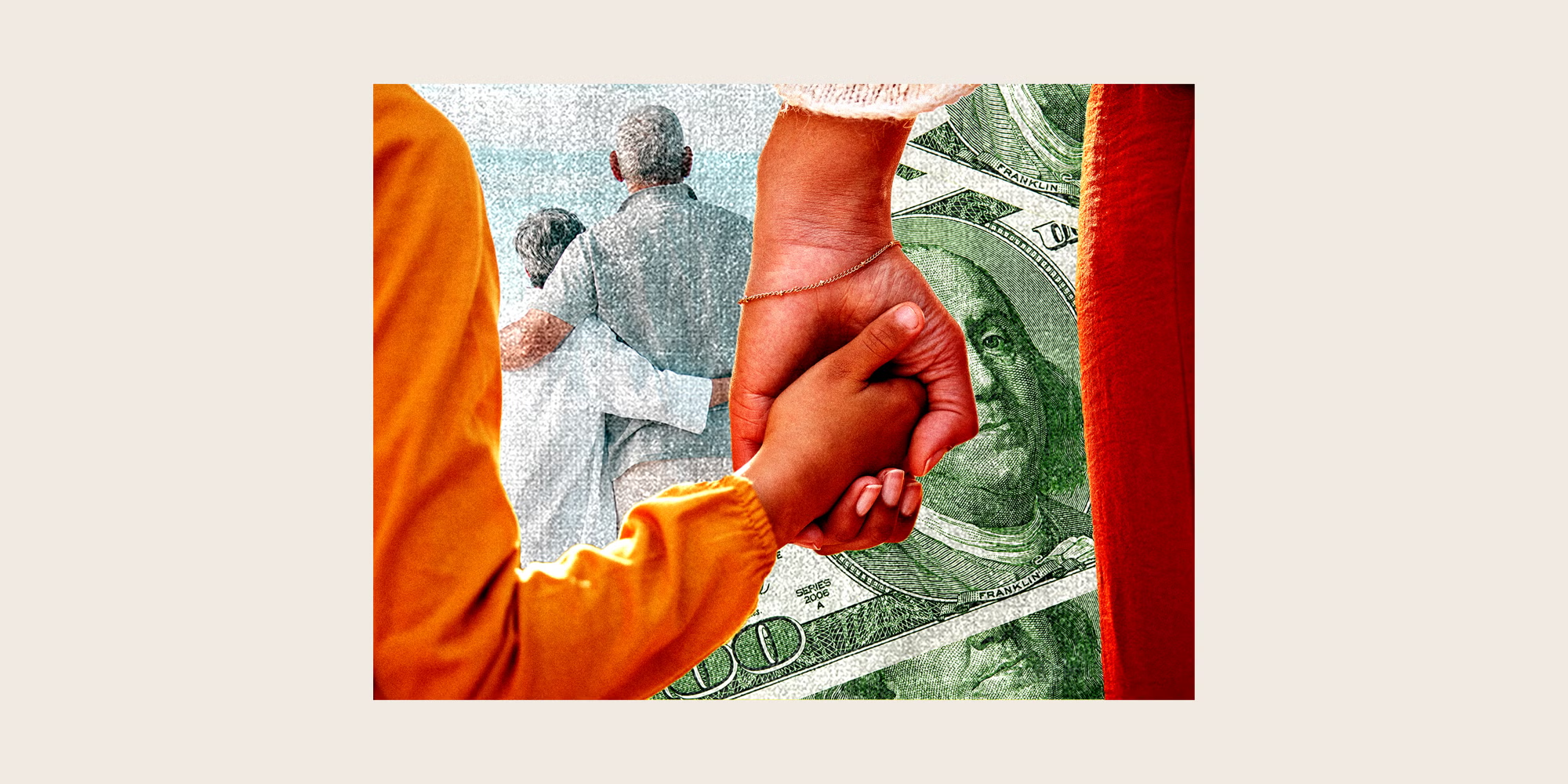

The costs of raising kids without grandparental care

May Udy, 32, is “on the cusp” of affording part-time childcare. She works full-time at her remote sales job, and her husband, Jackson, has a steady stream of work as a contract engineer in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Yet, the cost of even a few days of childcare for their two children, Noah and Hannah, aged 5 and 6, is untenable.

Nationally, care for one child ranges from $4,800 to $15,000 a year, and the prices are expected to keep rising. In Tennessee, the average annual childcare cost is $10,000-$11,000.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle agree that childcare is a significant financial strain. In a recent interview, JD Vance suggested parents should ask their families to pitch in. “Maybe grandma or grandpa wants to help out a little bit more,” Vance said. “If that happens, you relieve some of the pressure on all the resources that we’re spending on day care.”

For Udy, that isn’t an option.

She is one of those millennial parents who get no childcare help from their parents, whether due to distance or larger disagreements about raising kids.

According to Pew Research, baby boomers are staying in the workforce longer than previous generations, which means they aren’t always around to watch their grandkids. Some grandparents also set boundaries around babysitting because they want space to lead their own lives.

Udy’s in-laws live a five-hour flight away in Washington state, and she said that when they do visit, they are only interested in the “fun” side of being grandparents. They “don’t do diapers” and have never offered to babysit. Her parents, meanwhile, are on a church mission off the coast of Fiji for the next two years. It means she and her husband are spread thin all the time.

“We are always tired,” Udy said. “It’s easy to let jealousy slip in when our friends in similar situations have family support that will come at the drop of a hat.”

Americans are more atomized

For those who live far from family, raising kids can be an expensive and isolating experience.

Katie and Anthony Waldron live in Long Island, New York — a seven-hour drive from her family in Buffalo and a roughly 10-hour journey from his mother and relatives across the pond in Birmingham, UK.

It made sense for them to settle in Long Island with their 4-year-old son, whose name they withheld for privacy. Katie is in public relations, Anthony is a TV producer, and they are just an hour’s train from New York City, which has more job opportunities than their respective hometowns.

Still, it’s been harder than they anticipated to build a local community of friends who could actually watch their kid sometimes.

“Both of us being outsiders, we never recognized how challenging it might be,” Waldron, 38, said.

From the time their son was four months old, they paid $20,000 a year for day care until pre-K, which is free in New York. Now, they spend about $700 a month for two hours of care once his school day ends. They also hire a babysitter for $15 an hour when they need to run quick errands, which comes to about $60 total every few months.

But when that babysitter is unavailable, Waldron remembers how alone they are. She once had to list an emergency contact for her son’s pre-K application form. They didn’t have one, eventually just jotting down the name of a friend, even though she is often traveling for work. Waldron’s upstate siblings would be more than happy to jump in, but they live too far away to be helpful in an emergency.

“That was one of the most distressing things and made us really consider if this is the right place for us to be living,” Waldron said.

They are considering moving back to the UK, where they met when she was in college, to be closer to family and gain access to more affordable childcare services.

Waldron and her husband want a second child soon before they’re much older, or the age gap between their two kids is too wide. They can’t see how it would work if they stayed in the US.

“The burden of childcare costs and, equally, the lack of emotional support as we go through our parenting journey make it impossible to have another,” she said.

Standards for childcare are changing, too

Even with grandparents nearby and readily available, some parents face another obstacle to free childcare: vastly differing views on how to do it well.

“Parenting standards have become much more exacting,” Dr. Katie B. Garner, the executive director of the International Association of Maternal Action and Scholarship, a nonprofit academic organization focused on motherhood, told B-17. These days, parenting tends to be more child-focused, as millennials strive to be more mindful of their children’s mental health than their parents were with them.

Childcare, while expensive, has a certain appeal for millennial parents who have a firm idea of how they want their kids raised. An employee has to listen to what they want and will likely be up to speed on the latest parenting trends. A grandparent may be emboldened to do the exact opposite.

Daisy Montgomery tried to lean on her parents for help raising Ashton, her seven-year-old son who, like her and her husband, Barclay, was diagnosed with ADHD and autism.

“The few times that we did have my parents babysit my son, they really didn’t have the skills to support him,” Montgomery, 35, said. After sharing her son’s diagnosis with her parents, she felt dismissed. She said her dad told her there was “nothing wrong” with his grandson and that he was being “babied” with speech and occupational therapy.

Eventually, it led to her becoming estranged from them. Because Barclay is also estranged from his parents, they have no family support.

They had to start from scratch in finding caretakers in Fort Collins, Colorado. “It was really hard and lonely,” Montgomery said. While they were able to send their son to a free preschool for children with disabilities, they’d be called 45 minutes after drop-off and asked to come pick him up. She said they were told the school couldn’t handle him.

Over time, they have found like-minded people, including the parents of their son’s autistic classmates, who can help out with care now and then. They hired a babysitter, who also has autism, for around $120 a month. They also spend around $1,500 a year on respite care, short-term care service for children with disabilities.

“We’ve built this community with people who understand what it’s like to be autistic and disabled, and that’s made a huge difference for us,” Montgomery said.

Parents are toughing it out alone

There is another hidden cost of today’s expensive childcare.

Long-term, this impacts economic growth as much as it does individual families. “It’s why people are oftentimes not working more hours, not seeking the promotions, not going for the more aggressive career path,” Garner said.

Udy, who used to be a chemist in California, switched careers and moved to Tennessee after having a second child increased their childcare costs in the Bay Area to over $3,000 a month. Waldron limits how many clients she accepts because she has to take care of her son, too.

Garner believes American parents need much more government help. The US has one of the most expensive childcare systems in the world.

While the UK also has high childcare costs, Waldron is drawn to options such as 15-30 hours of free childcare a week and low-cost extracurriculars. She said a relative of her husband pays £5 (about $6.50) per session for his son’s after-school Lego club.

“So many parents would be so thrilled in America if they could have access to something like that,” Waldron said.