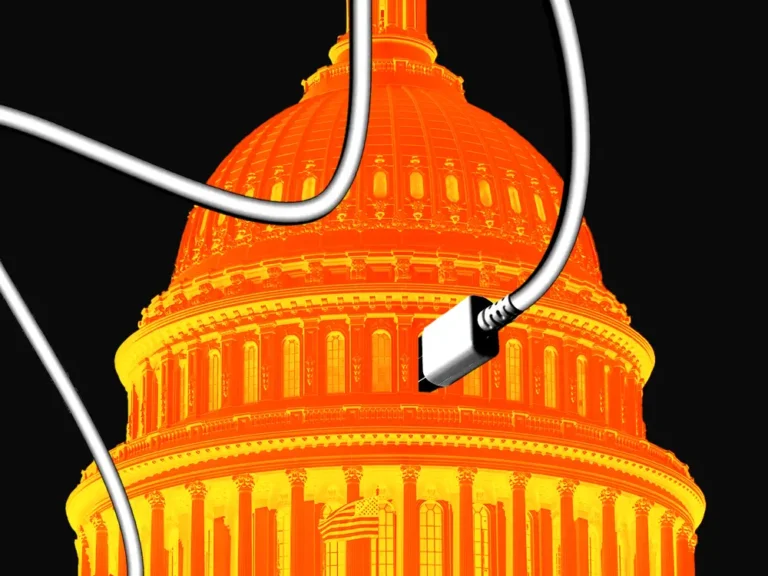

The DOJ wants Google to sell its Chrome browser. Here are the winners and losers if that happens.

A judge ruled in August that Google maintains an illegal monopoly in the search and advertising markets.

A possible breakup of Google just became slightly more likely.

The Justice Department on Wednesday asked the judge in its antitrust case against Google to force the company to sell its Chrome browser.

That follows Judge Mehta’s ruling in August that Google maintains an illegal monopoly in search and advertising markets. Google will get to suggest its own remedies, likely in December, and the judge is expected to rule next year.

If Google ends up having to sell or spin off Chrome, it would be a blow to the company. Meanwhile, advertisers and search rivals would likely cheer the news, according to industry experts.

Separating Chrome from Google and preventing default search placement deals “would put Google Search into competition with other paths for advertisers to reach potential customers,” said John Kwoka, a professor of economics at Northeastern University. “Advertisers would find competitors for their business, rather than needing to pay a dominant search engine.”

Chrome is a hugely popular Google product that the company leans on to grow and maintain its search advertising empire. Chrome holds 61% of the US browser market share, according to StatCounter, while 20% of general search queries come through user-downloaded Chrome browsers, according to the August ruling from Judge Mehta.

Distribution and self-reinforcing data

Chrome is a valuable distribution mechanism for Google Search, and a portal into the searching habits of billions of users.

When you open Chrome and type something into the search bar at the top, these words are automatically transformed into a Google Search. On other browsers and non-Google devices, that’s not necessarily the case. With Windows devices, for instance, the main browser defaults to Microsoft’s Bing search engine. And when there’s an option for users, Google pays partners billions of dollars to set its search engine as the default.

Chrome avoids all these complications and costs because Google controls it and sets its own search engine as the default for free.

Once this important distribution tool is in place, Google collects mountains of user data from the browser, and from searches within the browser. This information goes into creating higher-value targeted advertising.

There’s an equally powerful benefit of Chrome: When people use it to search on the web, Google monitors what results they click on. It feeds these responses back into its Search engine and the product gets constantly better. For instance, if most people click on the third result, Google’s Search engine will likely adjust and rank that result higher in the future.

This self-reinforcing system — supported by Chrome — is very hard to compete against. One of the few ways to compete is to get more distribution than Google. If Chrome were an independent product, rival search engines might be able to get a piece of this distribution magic.

In 2011, venture capitalist Bill Gurley called Chrome and Android “very expensive and very aggressive ‘moats,’ funded by the height and magnitude of Google’s castle.”

Google has also tapped Chrome as a way to reach users with new AI products, including Lens, its image-recognition search feature, as it tries to fend off emerging rivals such as OpenAI.

The lesson of Neeva

Many have tried to take on Google in the browser market, and many have failed. Take Neeva, a privacy-focused search engine launched by Google’s former ads boss Sridhar Ramaswamy and other ex-Googlers.

Not only did the startup have to develop a search engine from the ground up, it also had to build its own web browser to compete with Chrome because this is such a major source of distribution in the search business.

Neeva lasted four years before closing its doors.

“People forget that Google’s success was not a result of only having a better product,” Ramaswamy once told The Verge. “There were an incredible number of shrewd distribution decisions made to make that happen.”

A ‘manageable inconvenience’

Teiffyon Parry, chief strategy officer of the adtech company Equativ, said that losing 3 billion monthly Chrome users would be “no small blow” to Google.

However, Google has many other ways of reaching users and scooping up data, including Gmail, YouTube, a host of physical devices, and the Play Store. The company also has a standalone app that functions as a web browser and has the potential to effectively replace Chrome.

“Chrome has served Google exceptionally well, but its loss would be a manageable inconvenience,” said Parry.

Implications for the web

Lukasz Olejnik, an independent cybersecurity and privacy consultant, is concerned about what might happen to the broader web if Chrome is sold off.

“Chrome is adopting web innovations really fast,” he said, giving Chrome’s security features as an example of how Google has innovated.

Without Google’s financial support, Chrome might struggle on its own, and it’s possible that progress on the web slows, weakening the ecosystem, he explained.

“The worst case scenario is deterioration of security and privacy of billions of users, and the rise of cybercrime on unimaginable levels,” he warned.

Would Chrome even survive on its own?

One of the biggest questions is how a Chrome spinoff might work. A Bloomberg analysis valued Chrome at $15 billion to $20 billion if it were to be sold or spun off. Would antitrust regulators allow a major rival to buy it?

It’s “unlikely” that Meta would be allowed to acquire it, tech blogger Ben Thompson wrote on Wednesday. That would leave someone like OpenAI as a potential buyer, he said, adding that the “distribution Chrome brings would certainly be welcome, and perhaps Chrome could help bootstrap OpenAI’s inevitable advertising business.”

And if Google has to sell Chrome, will it also be banned from making distribution deals with whoever buys the browser?

“The only way [a spun-off Chrome] could make money is through an integrated search deal,” said tech commentator John Gruber on a recent podcast.

There may be ways around it. Earlier this year, a group of researchers published a paper analyzing Google Chrome’s role in the search market and within Google’s business (it should be noted one of the authors works at rival DuckDuckGo).

“The precedent set by Mozilla’s financial dependence on Google highlights potential challenges for Chrome in maintaining its operations without similar support,” the researchers said, nodding to the fact Google pays Firefox a lot of money to be its default search engine, despite Firefox’s dwindling user numbers.

The researchers proposed one way to divest Chrome without letting it die is to let Google still financially support it if necessary but block Google from exclusive contracts that make Google Search the default. They also suggested web browsers could be reclassified as public utilities.

“Under such a classification, Chrome’s agreements and decisions would be subject to heightened scrutiny, particularly to safeguard consumer welfare and prevent exclusionary practices,” they wrote.

Google’s response

Google plans to appeal any ruling, potentially delaying any final decision by several years. In a statement earlier this week, Lee-Anne Mulholland, Google’s vice president of regulatory affairs, said the DOJ was pushing “a radical agenda that goes far behind the legal issues in this case.”

“The government putting its thumb on the scale in these ways would harm consumers, developers and American technological leadership at precisely the moment it is most needed,” she added.