The rise of ‘shadow stand-ins’

The brazen new way employees are cheating their way to the top

Across the globe, a wave of workers are secretly outsourcing parts or all of their jobs.

Remi never intended to secretly outsource her job. It sort of just happened.

After graduating from college in 2019 with a degree in education, the Gen Zer found work at a Chicago publishing company. She did not love it. Most of her colleagues were decades older than her, and their struggles to use basic software forced her to become a one-woman IT operation. The work itself was uninspiring and relentless: On most days she juggled presentation slides, managed spreadsheets and databases, and formatted page layouts.

The pandemic provided a respite from the tedium of in-office interactions. But it didn’t lessen her workload, and she quietly began asking her boyfriend, a STEM major working in a lab, for occasional help. Certain she’d be fired for it, she didn’t tell her employer.

Then her mother died.

Remi was appointed executor of the estate, and settling her mother’s affairs was a never-ending nightmare: wading through countless gambling debts, maintaining the crumbling family home, and distributing the few remaining assets. Though she took a leave of absence from work and continued to rely on her boyfriend when she returned, she couldn’t keep up. Soon, she also turned to a childhood friend, who was unemployed and needed money. Remi proposed a plan: She’d pay her friend $100 a book to help with editing and formatting, saving her hours of work every week. The friend eagerly accepted. Her colleagues, meanwhile, remained clueless.

And just like that — although she didn’t know it — Remi had become part of a hidden movement that went far beyond her Chicago publishing company.

Across the globe, a wave of workers are secretly outsourcing parts or all of their jobs. Labor has never been easier to invisibly offload, thanks to a perfect storm of factors: globalized social networks, ubiquitous software tools, and the pandemic. An inadvertent byproduct of the rapacious, profit-seeking impulse that drives our global economy, this corporate subterfuge stretches from high-powered Silicon Valley techies to legions of low-paid helpers in India and Pakistan.

Welcome to the world of shadow stand-ins.

Stories about covert outsourcing are nothing new. Essay mills and faux test-taking have become perennial problems in academia, and gig-economy workers are occasionally caught lending their accounts to friends. Walter Keane gained notoriety in the 1960s for passing off “big eyes” paintings by his wife, Margaret, as his own. In 2012, a Verizon engineer was caught farming out his work to a team in China so he could browse Reddit all day. But in most workplaces, the idea of hiring someone to do your job for you seemed so outlandish that The Onion satirized it in 2009 as the natural endpoint to globalization and American laziness.

No longer.

I talked to dozens of players in the shadow stand-in economy, including people like Remi, hired helpers, and those who have watched colleagues or friends partake. (Citing reputational or professional risks, most spoke on condition of anonymity or asked to be identified only by their first or middle name.) Given its clandestine nature, it’s difficult to know just how many people the network scoops up. But providers told me they had seen a surge in popularity since 2020, a consequence of the pandemic and its attendant remote-work revolution. The past four years have transformed workplace norms, liberating millions from commutes and precipitating a wave of alienation from professional life — while providing eye-watering opportunities for the hungry or unscrupulous.

“It becomes very easy for people to take the support when working from home,” said one shadow stand-in who lives in India and who has been in business since 2019. “After the pandemic,” said another from Pakistan, the industry “boomed.”

There’s no one model for how shadow stand-ins work, and practitioners use different terms: outsourcing, delegating, proxy work, subcontracting, virtual assistants, offshoring, or the delightfully euphemistic “job support.” It ranges from doling out small tasks to providing someone login credentials for full remote access. Some people want a mentor, some want a crutch after using “proxy interview” services to cheat their way through the hiring process, and some just want the productivity guru Tim Ferriss’ “4-Hour Workweek” on steroids. Others use the free time to rake in cash by working multiple jobs, a twist on the concept of overemployment.

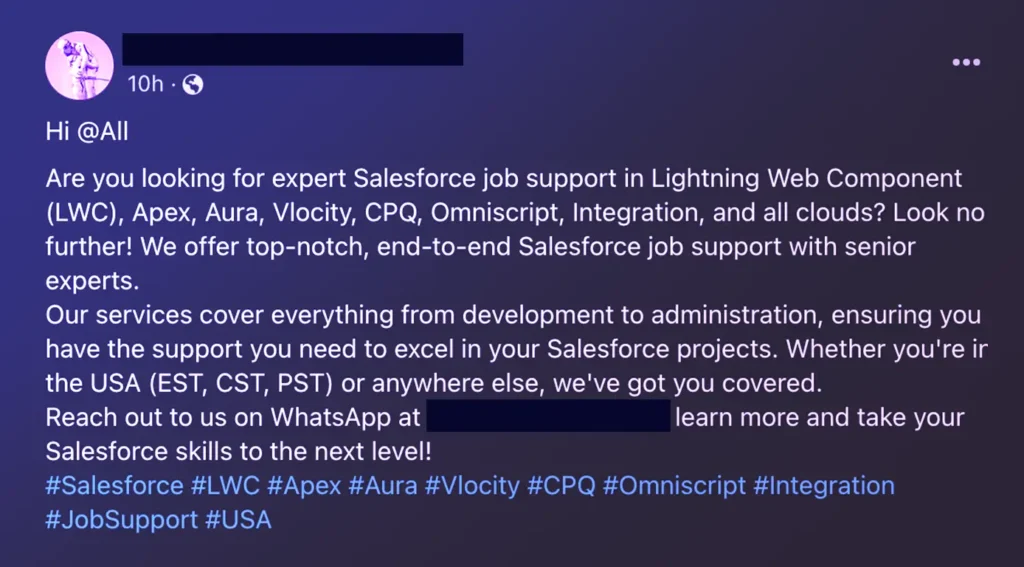

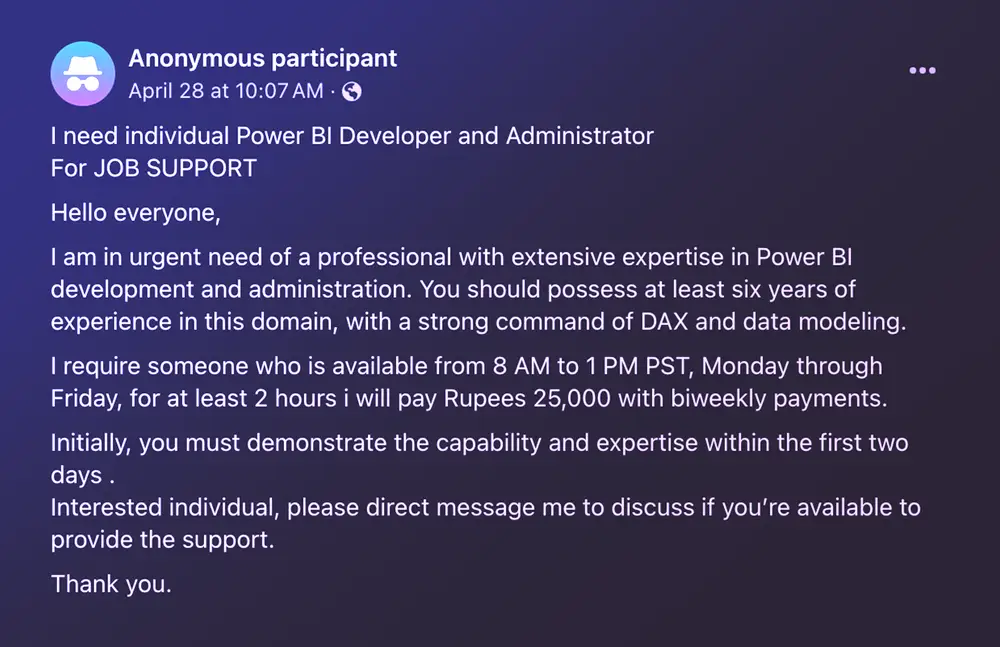

Though Remi recruited people she knew, shadow stand-ins are often sourced from a complex online web of faceless providers. Sites like Fiverr and Upwork are common conduits; a designer in the Southwestern US told me he would periodically hire two freelancers for the same job and discard the inferior work. Platforms like Facebook, Telegram, and WhatsApp are full of job support groups with thousands of members each. dedicated to matching providers and users. In one recent Facebook post, an Atlanta man struggling with his Salesforce-related job offered half his salary to anyone willing to quietly hold his hand through tasks and meetings. In another, a woman in San Jose, California, working for a major tech firm asked for help with a short programming assignment.

Facebook Groups are a popular forum for recruiting shadow stand-ins, providing a two-sided marketplace where workers and providers can connect to one another.

“Job support is nothing bad,” Raj Kumar, the Bengaluru, India-based cofounder of Onlinejobsupport.net, told me. He simply sees it as an “advanced version of training.” Like many professional job-support firms, his team often acts as a kind of black-market IT helpdesk, using screen-sharing software to dial in to their clients’ computers for a few hours a day to give pointers as they work — or completing the work themselves if the client would rather be elsewhere.

You could hire shadow stand-ins in many workplaces, assuming your boss isn’t looking too closely. But it’s much more common in jobs in technology and IT. SaaS tools and tech services like Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Amazon Web Services have become the plumbing for our global economy, used by everyone from fast-fashion retailers to nonprofits, and their cookie-cutter systems make it easy for anyone with the right skills to quietly step in.

For the past few years, an American Java developer named Kevin has been living in Southeast Asia and outsourcing his jobs — all three of them. With the help of a Filipino friend acting as a recruiter, he brought on three local “virtual assistants,” offloading nearly all of his technical work. He writes formal assignment sheets for each worker; “Implement a test for valid JSON in POST content,” reads a typical directive.

Needless to say, none of his employers — finance and construction firms — know about one another, and his workers are similarly in the dark. Even his location is a secret: He told his bosses he was based in the United States, and he works nights to avoid detection. “It’s low-cost labor or low cost of living, mostly,” Kevin explained. “I’m making three American incomes, but I’m paying Filipino rates to live.”

He’s an extreme example of a user of shadow stand-ins. But whether they’re juggling multiple jobs or outsourcing the odd task, they tend to have one thing in common: a deep skepticism of traditional corporate values.

Some believe if the work gets done, no matter how unconventionally, there’s no problem. “Everybody has a different moral compass and a different thing that they say: ‘This crosses the line for me,'” said Andrew, a consultant in Colorado who has outsourced work to freelancers and family members. He views “quiet quitting” — deliberately coasting at work — as far more odious. “I don’t believe somebody hires me for my time. They hire me to get results for them,” he said.

For many devotees, using shadow stand-ins isn’t just a preferred way of working — it’s a renegade professional philosophy.

Others, like the Southern California developer Brandon Nowak, have contemplated dipping their toe in the water. He told me that shadow stand-ins are an inevitable outcome to our system of making money. “Companies themselves are taking advantage of you, by hiring you to do work which they reap more value from you than they give to you. That is the basis of capitalism,” he said. “I’m not an anti-capitalist necessarily, but I don’t fault anyone — myself included — for looking to turn those tables on the companies themselves.”

There is one wrinkle to this line of thinking. Some shadow stand-in connoisseurs — particularly those who ship their work to offshore helpers earning much less — are arguably replicating the same structures they’re trying to rebel against.

“For-profit corporations are government-sanctioned psychopaths, existing only to predatorily and parasitically earn profit,” Kevin said. “Corporations are owed no moral obligation whatsoever, any more than a hen owes a fox moral consideration. The only rational response is to extract as much as possible.”

But, he conceded, “I readily admit I can’t provide a consistent response to the problem of pushing predator-parasite further down the line.”

Soon after hiring her friend, Remi had an awkward realization: They were bad at the job.

Sometimes, they made glaring errors. Reformatted manuscripts came back with page numbers inserted into paragraphs, or charts were missing data. Remi effectively demoted them, adjusting the arrangement to pay $10 for each individual chapter, but that created new problems: Since they took hours to complete what usually took her 30 minutes, she was effectively paying them less than minimum wage.

Their friendship suffered, too. “I’d give soft corrections on how I would like the work to be done, and they would be a little defensive about it, or wouldn’t take the note,” Remi said.

After two months, Remi decided to fire them, fibbing that she simply no longer needed help. She turned back to her boyfriend, who began working for her more consistently.

The dustup highlighted a key drawback to shadow stand-ins: While alluring, things can go horribly wrong.

Half a dozen workers at different companies in the US and India told me they knew of colleagues who had secretly outsourced work. Problems invariably piled up, they said: The work was inadequate; there were inconsistencies in communication; and organizational chaos abounded.

“If you can’t trust your employee — if they’re dishonest and they’re not telling you the truth about one thing — that could mean that they’re not telling you the truth about other things,” said Amber Clayton, a senior director at the Society for Human Resource Management, an HR industry body. “I wouldn’t want that individual within the organization, because who knows what they would do?”

Facebook’s anonymous posting tools in Goups have made it easy and low-risk for shadow stand-in seekers to advertise their needs.

Even when it goes right, managing a secret helper or two can be laborious. Your conventional workload may be lightened, but it’s replaced with finding and vetting helpers, delegating tasks, reviewing the completed work, and living in constant fear of being found out. “It required a lot of micromanaging,” said a backend engineer in Pennsylvania who hired shadow stand-ins to help him juggle multiple jobs. “It’s like you were working — but then on top of that, it became another task of just managing them.”

Occasionally, the problems can have implications far beyond the workplace.

In December, Tim Woodruff, a ServiceNow developer in Washington state, got a curious LinkedIn message from a “consulting” firm. “We will send job applications to remote jobs and schedule job interviews for you,” the message read. If he got the job, the firm promised to “attend everything related to programming.” All he had to do for whatever role he landed was attend meetings, and give the firm half of his salary.

Woodruff despised workplace deception, even joining job support and proxy interview-focused Telegram groups to disrupt them in his spare time. “I’m autistic, and rules help me make sense of the world, and I don’t like it when they’re just ignored and no one seems to care,” he told me. He decided to go along with the chicanery to see where it led.

He joined the firm’s Slack channel and let it apply for jobs on his behalf, even attending some job interviews. He said he noticed a disquieting trend: Many of the jobs he was interviewing for had national security implications, including tech consultancies working with the Secret Service and the Department of the Treasury. Other applications were to financial institutions. Woodruff said he reported the firm to the FBI. (A bureau spokesperson said they couldn’t confirm the existence of any investigations.)

Ranjan, a software engineer from Bengaluru, is regularly approached by job-support firms trying to hire him to work for their clients. “We will keep your name, all data confidential. We do not deduct tax from your salary,” one recruiter wrote to him on LinkedIn. “Your package will be Beautiful, trust me.”

The pitch hints at the stark economic power disparity that underpins shadow stand-ins, he told me: Most job support comes from countries like India and Pakistan, where wages are low and “desperate” workers will provide cheap labor. Pay rates for shadow stand-ins are “definitely more than what people earn in their regular payday, that’s for sure,” he said.

Despite mixed feelings about the practice, Kiran, a shadow stand-in based in Bengaluru, has continued to provide help because of the money he earns. “They are faking,” he said of clients. He has watched, frustrated, as clients coast through high-paying jobs, lying about skills and taking job opportunities “which are supposed to be for honest people who are actually experienced.”

The same economic disparities that underpin much of our globalized economy power the shadow stand-in trade, which stretches from tech workers in the US to low-paid helpers in India.

Still, Western pay remains an alluring prospect to many. “I think it’s a win-win situation,” said Rahul, an Indian developer whose friends have provided job support and who is interested in doing it himself. “We get paid peanuts anyway, so this is an extra source of income. It usually pays better, too.” Andrew, the Colorado consultant, argued that both parties agree on a price they’re happy with. “I feel like I pay people fairly,” he told me.

Peter Steele, a Michigan developer, has an Upwork account and receives unsolicited pitches several times a year offering to apply for and complete jobs using his name in return for a slice of salary. “They talk about how getting clients is extremely difficult when you’re not based out of the United States,” he said.

High demand has paved the way for intermediaries who match clients and helpers — a veritable nesting doll of outsourced hustle. Many of them aren’t shy about their businesses: Kumar’s job support firm Onlinejobsupport.net, for example, claims on its website to have more than 500 happy clients across 25 countries — focusing on popular systems or tools like Java, AWS, Hadoop, and React. (It might be wise to be skeptical of any one provider’s marketing claims, but there’s clearly a bustling ecosystem.)

Many of these intermediaries aren’t shy about their business, either. You can even find some marketing their services on LinkedIn.

The pandemic years were a boom time for shadow stand-ins. Now the winds are shifting.

Return-to-office has forced some delegators to give it up — it’s harder to screen-share and outsource tasks if you’re sitting in a cubicle — while others are reduced to huddling with helpers after returning home. Providers told me they’re feeling the pinch, but there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle.

The model has been proved, the global supply chain is there, and worker attitudes have shifted. “If I died at my desk tomorrow, my job would be posted online before my funeral,” said one Oregon worker whose colleague tried to outsource their job.

Others question why secret delegating might be stigmatized more than other tactics. “Assuming you are not sharing proprietary data,” Andrew, the Colorado consultant, asked, “what is the difference from outsourcing your work vs using an AI or software tool to automate your work?”

And while shadow stand-ins feel like a uniquely modern, internet-enabled phenomenon, its roots run much deeper. “Historically, at least in certain trades, both in the US and other countries, the household unit was the unit employed to do the work,” said Michel Anteby, a professor of management and sociology at Boston University. He offered up the New England spinning industry as an example. “No one really cared or tracked if it was the husband, the wife, the kids who are doing the job.”

Remi fits neatly within that framework.

Her boyfriend, it turned out, was a great worker. He could swiftly complete technical tasks that usually took her all day, and she didn’t pay him; they had already merged finances when her mother died. They continued the arrangement until she quit a year later. But even after she left, Remi received intermittent texts from old coworkers asking for help. She never replied. She had no interest in letting the company exploit her labor.

Today, the Chicagoan has no regrets. “I personally come from a background where I am very anti-corporation,” she told me. “I don’t personally see the harm in it — especially because if my company isn’t going to do its best to keep me happy and healthy, and have my best interests in mind, then that falls upon me to ensure that that’s happening for myself.”

Remi now works in an education-related field. Her boyfriend is employed as a remedial tutor at a school, and she sometimes lends him a hand, formatting his presentation slides and doing other miscellaneous work.

His employer doesn’t know, and the couple have no plans to stop.