There are so many drones in Ukraine that operators are stumbling onto enemy drone feeds and picking up intel

There are so many drones in the skies above Ukraine that drone operators occasionally stumble onto enemy drone feeds and pick up unexpected intel. Neither side can be sure, though, when it will luck into this — or when the other side will.

Drones, including cheap first-person-view ones, are being used more in Russia’s war against Ukraine than in any other conflict in history. They are being used to attack troops and vehicles, complicating battlefield maneuvers, and they’re so prolific that ground troops often struggle to sort out which ones are theirs.

Ukrainian drone operators told B-17 that extensive drone warfare had resulted in unintentional feed switching.

When this occurs, operators on one side of the battlefield can see the feed of the other side’s drone — typically airborne devices that can target soldiers directly or identify enemy positions that will then be targeted. A drone operator in Ukraine said being able to see Russian drone feeds was “useful because you see where the enemy drone that wants to destroy you is flying.”

That gives the unit a chance to take defensive action.

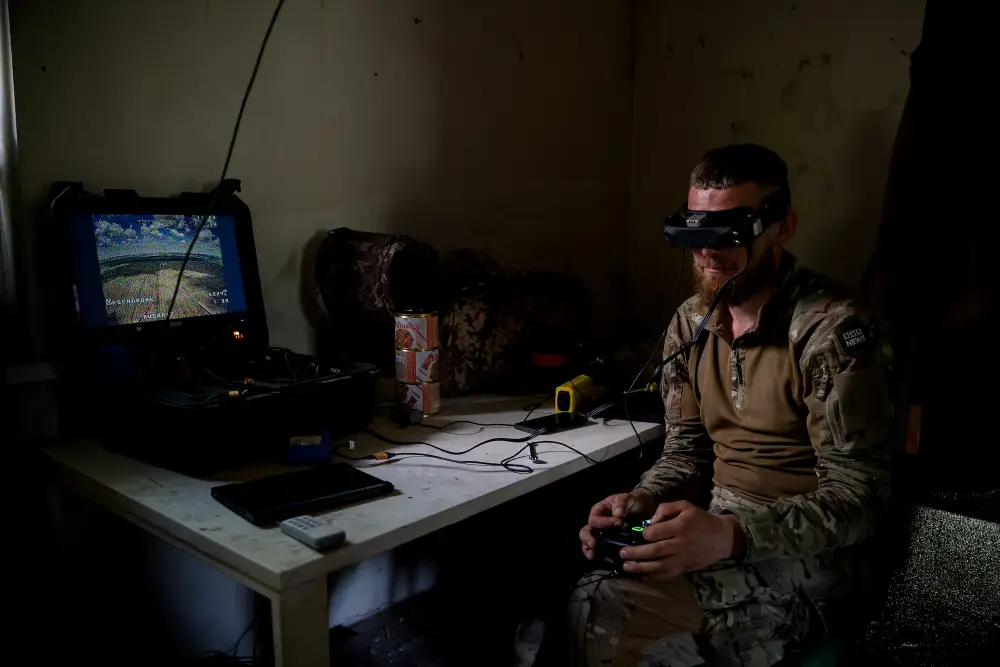

Ukrainian soldiers watching a drone feed in an underground command center in Bakhmut.

Samuel Bendett, a drone expert at the Center for Naval Analyses, described it as the wartime version of a common civilian occurrence: When you drive in your car and have your radio at a certain frequency, your radio can flip between different stations that use the same frequency.

Fight for the spectrum

Jackie, a US veteran fighting in Ukraine, said “two fights” were being waged by drones in Ukraine. “There’s one that you can see on video,” he said. “And there’s one that’s completely invisible.” That invisible fight takes place in the electromagnetic spectrum.

The electromagnetic spectrum can get “full” and “crowded,” he said. When there are enough drones in an area, he continued, operators have “a lot of the feeds between those drones transferring, basically switching between operators without intent.”

When that situation happens, it means “the drone guy would just suddenly see some other drone’s feed,” Jackie said. So when enough drones are in the sky, everyone is “constantly switching feeds between some other drone that they’re not flying.”

A Ukrainian serviceman of the 35th Separate Marine Brigade operating a drone at a training ground in Ukraine’s Donetsk region.

Bendett said it was possible to do this deliberately if you know the frequency your adversary is operating on, but most of the time, he said, it’s accidental.

He said this sort of thing happens “because technologies for both sides are similar, and there’s only so many operating frequencies you can hop on to actually pilot your drones.”

Advantages and disadvantages

As neither side has dominated the electromagnetic spectrum through electronic warfare, both sides are experiencing all the advantages and disadvantages of these developments. Sometimes Ukraine is collecting intel, and sometimes it’s Russia.

The feed can help operators helplessly realize an attack is incoming, and “it also can be very informative for drone crews, experienced ones, to kind of determine the tactic of the adversary, how far the drone flies, how fast it flies, what’s the drone route, what the drone is looking for, and so on and so forth,” Bendett said.

But it’s a hard thing to plan for given the chaotic nature of these occurrences.

Jackie shared that Ukraine had attempted to “play games with the signals,” but Gregory Falco, an autonomous systems and cybersecurity expert at Cornell University, said it’s “probably not predictable when you’d be able to get these capabilities.” It’s more about seizing the advantage when the opportunity arises.

Switching signals

Falco said it would be difficult to tell whether the enemy has access to a feed because “you don’t have absolute certainty of where your band is at a given time and where you’re projecting.”

A Ukrainian serviceman launching a drone during a press tour in the Zhytomyr region.

There are questions about whether this could be taken further, though, going from accidental insight to deliberately pirated drones. Right now, that’s more theory than practice.

Whether any Ukrainian or Russian operators could actually get control of the other side’s drone, rather than just being able to see through its eyes, probably depends on the drone, Falco said.

He said the spectral bands used to see drone feeds are probably different from the ones that control it. And the bands used to receive signals — that let the operator see what the drone can see — are typically less protected than the ones that send the signals, which is how operators tell drones what to do.

He said the feed switching was “bound to happen” with so many drones in the sky and with different types of electronic warfare in play.

Solutions, Falco said, could involve something like added encryptions for drone feeds. But given the fast-moving, chaotic, and desperate nature of a lot of the fighting and the fact that drone operators can go through multiple drones a day, it may not be worth it. And if that’s the case, this kind of thing will keep happening.

He said it was the type of thing civilians would frequently see if there were less regulation. “If we didn’t have rules,” and if the likes of the United Nations body that allocates the radio spectrum didn’t exist, “and companies didn’t bother playing by the rules, then this would be a normal occurrence,” Falco said.

Then, he added, it would just be “a total shit show of hearing and seeing everything that you’re not supposed to see.”

A Ukrainian soldier watching a drone feed from an underground command center in Bakhmut.

Ukraine, often short on other weaponry as it faces Russia’s larger military, has been relying on drones, including to make up for ammunition shortages. And even the cheap drones have let Ukraine destroy Russian equipment worth millions.

Ukraine’s drones are critical assets in the war and are said to account for at least 80% of Russia’s frontline losses. “Drones are super vital,” Jackie said. “They’re one of our more clever casualty-producing weapons.”

Correction: January 1, 2025 — An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of an autonomous systems and cybersecurity expert at Cornell University. His name is Gregory Falco, not Gregory Falso.