There’s already a queue of cargo ships backing up at US ports

A container ship at a facility in Bayonne, New Jersey, on Monday.

For the first time in nearly 50 years, international maritime trade has come to a standstill in the Eastern US.

As the International Longshoreman’s Association strike heads into its third day, the stoppage is already having an immediate effect on the flow of goods through East and Gulf Coast ports.

At least 38 container vessels were backed up at US ports on Tuesday, the first day of the strike, up from three on the preceding Sunday, Reuters reported, citing Everstream Analytics data.

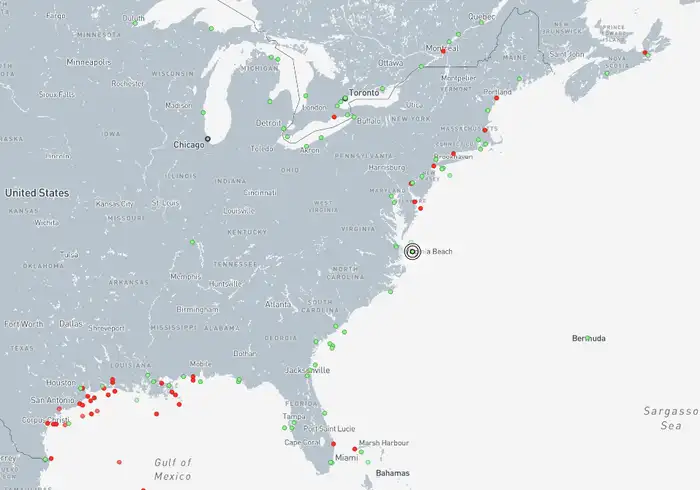

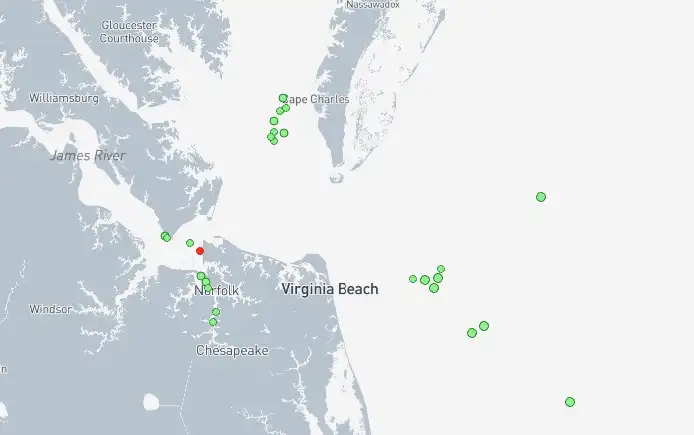

A B-17 review of ship-tracking data shows a growing number of cargo vessels and tankers at anchor near closed facilities, including New York, Virginia Beach, Savannah, Miami, New Orleans, and Houston.

Cargo vessels (green dots) and tankers (red dots) at anchor outside Eastern US ports.

Andrew Coggins, a professor at Pace University, said each one of those ships represented a company losing money.

“The whole business model of the container-shipping industry is to spend as little time in port as possible,” he told B-17.

“The ship makes money when it’s sailing from A to B,” he added, saying that some vessels were probably adjusting their speeds in order to delay their arrivals for as long as possible so as not to sit idly at anchor.

But even if the strike were to end tomorrow — which is extremely unlikely — a new problem is emerging: dock space.

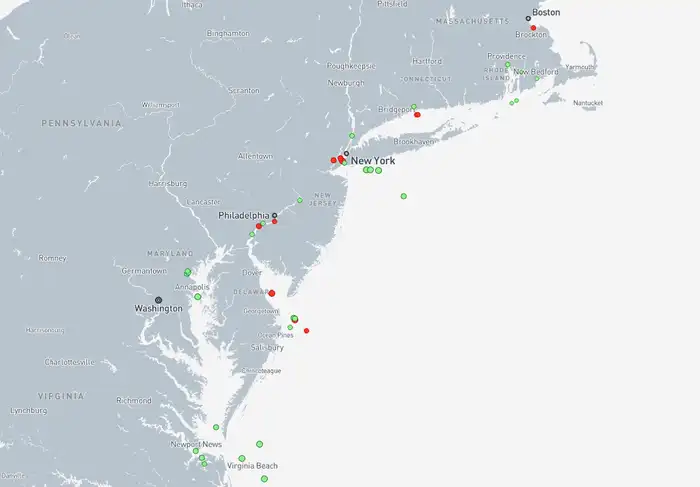

Cargo vessels (green dots) and tankers (red dots) along the Mid-Atlantic.

Ports have only a limited amount of square footage upon which to stack and store containers, and once that capacity is full, things start to unravel quickly.

A working port is an intricate dance of trucks, cranes, and ships, all coordinating to exchange outbound containers for inbound ones.

Stopping that flow even for a single day creates all manner of headaches, such as spoiled produce and canceled journeys, Coggins said.

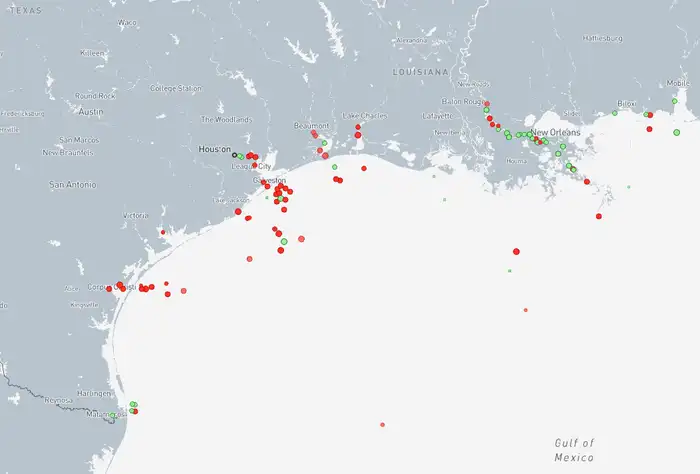

Cargo vessels (green dots) and tankers (red dots) along the Gulf Coast.

Burt Flickinger, the managing director at the retail consulting firm Strategic Resource Group, said only about eight to 12 ships were ordinarily in a port’s queue at any time, and those were typically turned around in a matter of hours.

He also estimated that only about 15% of Eastern US cargo volumes could feasibly be rerouted to Western ports, though unionized workers there would still not accept it during the strike.

“If [the strike] goes into next week, each passing week will lead to half a month to a month’s backlog processing, and each day’s delay could result in 1% to 2% price increases, depending upon the category,” he said.

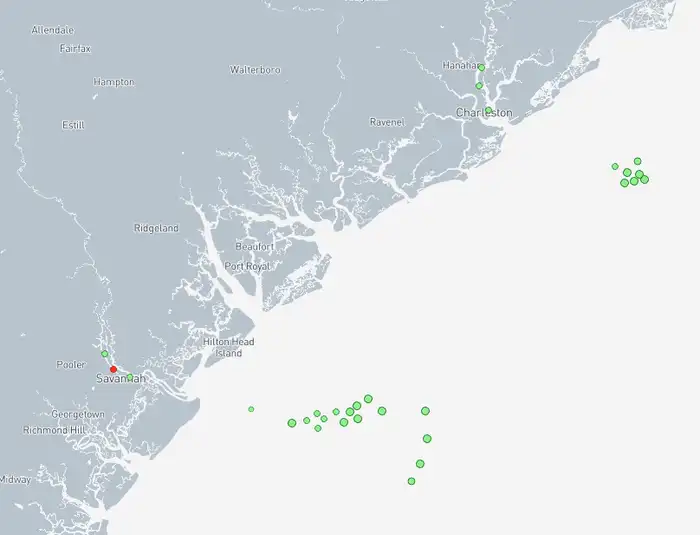

Cargo vessels (green dots) and tankers (red dots) outside Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Interestingly, Brandon Daniels, the CEO of the AI supply-chain company Exiger, said some of the effects of the strike on the supply chain had been evident for weeks leading up to Tuesday’s port closures.

Daniels added that imports of medicines and other critical materials had also been rerouted to air freight, driving up rates for that mode.

As alternative channels reach their own capacity limits, he said, “your overall cost is going to go up, but the efficiency of the system then gets significantly bogged down.”

Cargo vessels (green dots) and tankers (red dots) outside Norfolk, Virginia.

The White House has given no indication so far that it would invoke the Taft-Hartley Act to force the ILA and the US Marine Alliance to the bargaining table in the interest of national health or safety.

But the damage from Hurricane Helene, the ongoing hurricane season in the Atlantic, and the disruption of critical supplies leave little room for error.

“I would assert that we’re already there,” Daniels said.