This radical plane concept with an all-in-one wing could be the future of flight. See the leading designs from startups and Airbus.

Passenger blended-wing concepts from Airbus and startups JetZero and Natilus hope to shake up the airline industry.

Aircraft manufacturers are racing to build the jet of the future as airlines demand more efficient planes.

Among the most likely concepts is a “blended-wing” body aircraft, which combines the fuselage and wing into one. This deviates from the traditional tube-and-wing design that has been the norm since the start of commercial aviation.

The all-in-one wing can reduce drag by up to 30%, helping reduce the amount of fuel needed, according to the US Air Force, which plans to use the design in a prototype.

A handful of companies have announced plans to build these unique vessels by the 2030s, including startups JetZero and Natilus and long-standing planemaker Airbus. Boeing has dabbled in blended-wing research but doesn’t have plans to build one yet.

Natilus and JetZero are starting from scratch and targeting different markets, but they have the same overarching goal: puncture the Airbus-Boeing duopoly.

Natilus is developing a 200-passenger narrowbody jet called Horizon to fill a perceived aircraft capacity gap over the next 20 years, while JetZero plans to build a giant 250-capacity widebody called Pathfinder to replace aging Boeing 767s.

Airbus could maintain its market lead with its 200-passenger “ZEROe” blended-wing concept. The company has decades of experience designing commercial airplanes — leading the industry with its best-selling Airbus A320 family of similar capacity.

All three companies have found what they think is the secret sauce in the giant flying wing. It is poised to greatly improve fuel burn, open up a wider cabin, and offer airlines better overall economics while still meeting route and infrastructure needs.

Blended-wing planes are essentially one giant wing.

A scale model of the Airbus blended-wing concept aircraft at the Farnborough Airshow in 2022.

Nautilus CEO Aleksey Matyushev told B-17 that banking on the airframe to reduce emissions is a better strategy than relying on sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF. Analysts have previously told B-17 that SAF is expensive and won’t be available in the quantities needed to meet the industry’s 2050 net-zero goal.

A lighter airframe is key to blended-wing efficiency.

A rendering of JetZero’s USAF blended-wing prototype.

Matyushev said a lighter airframe and engines, combined with the more fuel-friendly wing that maintains standard capacity, would allow its Horizon jet to be up to 50% more efficient per passenger.

JetZero also expects its Pathfinder to burn 50% less fuel and has already partnered with the US Air Force to develop a blended-wing prototype. Airbus’ announced ZEROe concept would run on hydrogen with zero emissions.

University of Illinois aerospace professor Michael Bragg previously told B-17 that the development of lighter yet still strong composite materials is key to reducing fuel burn on blended-wing aircraft designs.

The engines sit in the rear of the airplane.

Airbus’ six-foot-long blended-wing demonstrator was unveiled in 2020 as a test-bed for these delta-wing ideas.

JetZero, Natlius, and Airbus’ blended-wing concepts have two engines attached to the back instead of under the wings, like most modern jetliners. Airbus said the engine location would reduce noise.

JetZero plans to borrow engines from planes like the Boeing 737. Matyushev said Natilus is in talks with manufacturers to develop its own blended-wing capable engine.

He said building a new engine from scratch is too risky. Airbus’ blended-wing concept would use zero-emission engines as it strives for a hydrogen-powered commercial airplane.

The cabin would be as unique as the airframe.

A rendering of an Airbus blended-wing cabin.

A blended-wing plane would have a much wider cabin than a traditional tube-and-wing design, meaning the rows could be more than a dozen people long.

JetZero said the cabin would allow for more efficient boarding and deplaning, and more carry-on baggage space would eliminate the need for pesky gate checks.

Nautilus said its wider cabin, which is uniquely planned with two levels, could be a nuisance for people stuck in the middle of the jet far away from windows. Still, it provides more legroom and opens up space for things like a kids’ play area or a lounge.

The planes should work with existing airport infrastructure.

It’s easier to launch a new plane type if it can fit into existing airport infrastructure. Pictured is a rendering of Pathfinder.

Aircraft manufacturers don’t want airlines or airports to have to spend a lot of money to accommodate a new jet type. The blended-wing plans are designed to fit into existing airport infrastructure.

JetZero, for example, said Pathfinder could fit into existing Airbus A330 gates, while Natlius said Horizon could fit into current narrowbody ones.

Small blended-wing demonstrators exist — but no full-scale prototypes are flying just yet.

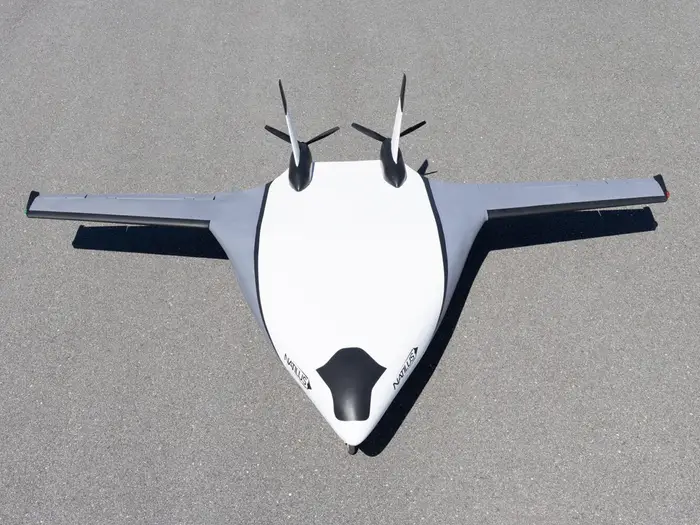

Subscale prototype of Natilus’s Kona aircraft.

As of now, all of the full-scale commercial blended-wing concepts remain renderings, but demonstrators have been built to test and validate the technical specifications and performance of blended-wing designs.

Natilus’ prototype is not for Horizon but for its cargo version called Kona, on which Horizon is based. Airbus and JetZero have also built demonstrators.

Airbus had a six-foot-long demonstrator called Maveric. It debuted in 2020 and was used to evaluate concepts like airport compatibility, maintenance, and safety, which would help with the development of ZEROe.

JetZero and Natilus hope to break the Airbus-Boeing duopoly.

Airbus is the top-seller for narrowbody jetliners, surpassing Boeing.

Airbus and Boeing have been the world’s two major commercial aircraft manufacturers for generations. However, supply chain issues at both, plus Boeing’s ongoing quality and production problems, may have opened the door for JetZero and Natilus.

“We decided to move into the narrowbody market because it’s the biggest opportunity over the next 20 years,” Matyushev said. “40,000 new narrowbody airplanes need to be built in that time, but Airbus and Boeing’s capacity outlook shows they can only produce 15,000 each, so we want to fill that capacity.”

JetZero said Pathfinder could replace Boeing 767s or similar traditional widebodies. The company has carrier attention, with Alaska Airlines announcing an investment in August.

There are still obstacles to overcome.

An interior rendering of JetZero’s Pathfinder.

JetZero, Natilus, and Airbus are shooting for entry to service in the 2030s, meaning the reality of blended-wing is still years away. And there are plenty of challenges.

One is ensuring the jet can withstand the expected load bearings. Another is convincing people to sit far from windows, but Matyushev said people would adapt to that if they had more space.

Airbus and JetZero face the complications of developing a hydrogen-powered engine type. Certifying a new plane type will also be long and tedious, with its own set of obstacles, including pilot training.

Larger blended-wing designs like JetZero’s also have to consider evacuations, which could take longer with fewer exit rows.

Blended-wing planes have already been flying for years in the military.

The B-21 Raider is among the blended-in wing planes bought by the USAF.

While a blended-wing passenger plane is a relatively new concept, the aircraft type has been flying for the US military for decades.

Northrop Grumman’s latest version is the long-range B-21 Raider stealth bomber, with which the US Air Force is conducting flight tests.

Its shape is similar to that of the B-2 bomber predecessor, which was first delivered to the USAF in 1993.