Under the Microscope: Cochrane’s COVID-19 Vaccines Review

News Interpretation

Cochrane’s review of COVID19 vaccines has received little attention, in stark contrast to the worldwide media attention paid to its review of face masks.

Because Cochrane reviews have been praised for being “rigorous” and “trustworthy,” it is prudent to apply the same scrutiny to the most recent update of the “Efficacy and safety of COVID19 vaccines.”

Findings of the Cochrane Review?

The review, which will be published in December 2022, examines 41 randomised controlled trials of 12 different vaccines, involving over 400,000 people who had never been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

According to the review, most trials lasted no more than two months and were conducted prior to the emergence of potentially harmful variants such as Omicron (up to November 2021).

The authors conclude with “high certainty” that most of the available vaccines could reduce symptomatic COVID19, and in some trials, they could reduce severe or critical disease when compared to placebo (which was mostly saline).

It also concludes that there is “probably little or no difference between most vaccines and placebo for serious adverse events.”

The authors acknowledged that the results could not be generalized to pregnant women, people who had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2, or immunocompromised people due to trial exclusions.

A Flawed Review?

Researchers Peter Doshi, Joseph Fraiman, Juan Erviti, Mark Jones, and Patrick Whelan recently published a critique of the Cochrane review.

The critique raises serious concerns about the Cochrane authors’ conclusions.

Doshi et al. are the same researchers who reanalyzed the pivotal mRNA trials and discovered that for every 800 people vaccinated with an mRNA vaccine, one additional serious adverse event (SAE) occurred.

This contradicts the findings of the Cochrane review, which found “little or no difference in SAEs compared to placebo.”

Doshi et al. point to significant flaws in the Cochrane review as possible explanations for the contradictory findings.

In Moderna’s trial reports, for example, SAE tables included efficacy data on individuals suffering from severe COVID-19, who were almost entirely in the placebo arm. Cochrane did not remove the efficacy data before presenting its analysis of Moderna vaccine SAEs, resulting in tabulated results that mask the true rate of harm.

According to the Cochrane review, the absolute difference in SAEs between most COVID vaccines and placebo “was fewer than 5/1000 participants.” This is equivalent to one in every 200 people, which is not uncommon, and contradicts Cochrane’s stated conclusion of “little or no difference.”

Another flaw in Cochrane’s review, according to Doshi et al., is the “composite endpoint” used to categorize “severe or critical COVID-19” cases.

According to Doshi’s team, the endpoint includes many participants who were not “severe or critical.”

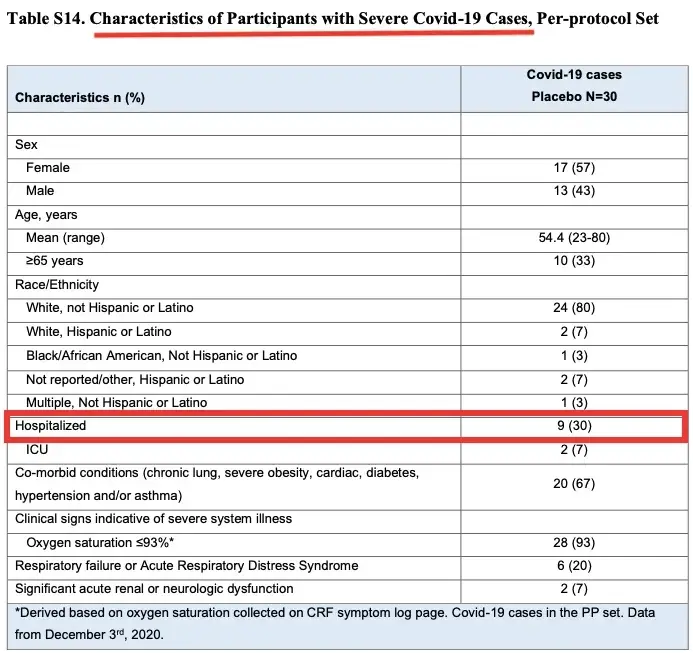

In the Moderna trial, for example, 21 of 30 cases were not hospitalized (see table).

There was also an issue with how “COVID-19 cases” were counted in the trials, which carried over into the Cochrane review when evidence was synthesised (garbage in = garbage out).

Before counting COVID cases, the trial sponsors waited one week (Pfizer) or two weeks (Moderna) after Dose 2.

To put it another way, COVID cases were not counted until 4 or 6 weeks after Dose 1 (see table).

Excluding all cases in the 4-6 weeks following Dose 1 is “particularly concerning” to Doshi et al. because there was very little follow-up time before the manufacturers decided to unblind the trials and offer the vaccine to the placebo group (median follow-up 2 months after Dose 2).

Another issue raised by Doshi et al. is that the mRNA vaccines were highly “reactogenic,” meaning they were likely to “unblind” the participants and bias the trial results. People in the vaccine group, for example, took more medications to reduce their fever after treatment than those in the placebo group, making it easier to guess which treatment they had received.

Nonetheless, the Cochrane reviewers rated the trial’s risk of bias due to blinding as “low.”

The Cochrane review also claims that it is “unclear if and how vaccine protection wanes over time” and that the evidence in their review is “up to date to November 2021.”

Doshi et al., on the other hand, argue that this is incorrect. The Cochrane review includes two papers [1,2] in which Pfizer demonstrated that efficacy against COVID-19 declines over time—vaccine efficacy had waned to 84% 4 months after Dose 2.

Finally, the Cochrane review trials primarily included healthy people who had never been exposed to the virus, so the efficacy outcomes are no longer applicable to the majority of people who have recovered from single or multiple infections. Similarly, pregnant women and immunocompromised people are not eligible for the trials. Despite being a significant limitation, the Cochrane reviewers did not emphasize it.

Cochrane’s Response?

Isabelle Boutron, a professor of epidemiology at Université Paris Cité and the director of Cochrane France, received a media inquiry with a list of questions.

Boutron confirmed her team had received Doshi et al.’s comments but did not respond to further questions, instead writing in an email: “We are working on the responses, which will take some time to check and respon[d] adequately to each point.” We will, of course, notify you when our responses are complete.”

There is no time limit for Cochrane authors to respond to criticisms of their reviews; some have taken years. Doshi et al.’s critique of Cochrane’s review of HPV vaccines, submitted in 2018, has yet to receive a response.

If Cochrane accepts Doshi et al.’s criticisms and revises its review accordingly, it will undoubtedly reach a very different conclusion than it currently does.

Originally posted on the author’s Substack and reposted from the Brownstone Institute.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of The Epoch Times.