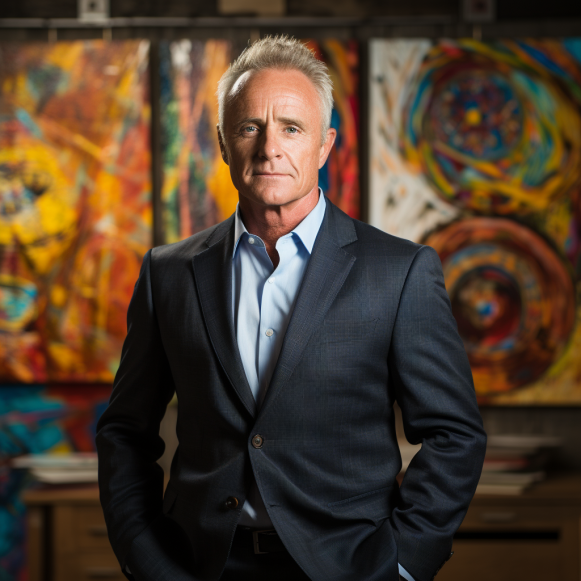

VC Ford Smith used psychedelics and biohacking to pull himself out of a deep depression. Here’s why he’s backing more startups in the space.

- Ford Smith turned to psychedelics to treat severe depression.

- His experience inspired him to focus his investment firm on backing psychedelic startups.

- Though VC funding slowed in 2022, investors are still eager to fund promising young psychedelic companies.

When Austin-based Ford Smith decided to wean himself off Adderall and SSRIs in 2016, he found himself in a dark place.

“I previously couldn’t look anyone in the eye, but with SSRIs, I was the most confident person in the room, maybe too confident,” he told Insider in an interview. “When I got off of them, it was like I hit rock bottom.”

One of the things that finally helped him regain his confidence and balance his mental health was ayahuasca, a plant-based psychedelic traditionally used by Indigenous people in South America.

“I could have stared at anyone for hours after the first ceremony,” he said.

Smith, a venture capitalist who got his start in the early days of the cannabis startup craze, was inspired by Ayahuasca to rethink his entire investment thesis and begin focusing on startups in the growing psychedelics space. As a result, his venture studio and incubator Ultranative has spent the last few years closely collaborating with early-stage companies to reimagine the world of psychedelics and how and why they are consumed.

Psychedelic drugs are expected to be a $11.29 billion industry by the end of the decade, and they are no longer limited to the magic mushrooms, or psilocybin, that your hippy friend indulges in on occasion. While recreational use of hallucinogens (a class of drugs that includes psychedelics and can cause hallucinations and changes in one’s perception of reality in certain doses) is on the rise, so is the use of psychedelics to treat mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as to solve larger societal problems.

While the use, sale, and possession of psilocybin is illegal at the federal level in the United States, some states, including Oregon and Colorado, have decriminalized the substance in recent years. Coupled with bipartisan support for research into the substance’s potential therapeutic benefits, there is growing public support for startups innovating in the space.

Venture investment in psychedelics fell more than 70% from $1.9 billion in 2021 to around $526 million in 2022, as VC funding fell across the board. However, venture capitalists, including Smith, are still placing large bets on promising startups in the space.

“The psychedelics revolution is happening again, and my whole experience with Ayahuasca influences everything I do,” Smith said.

When suffering from treatment-resistant depression. Smith finally found relief in plant-based psychedelics.

Smith, who was born and raised in a small town in Texas, entered rehab as a teenager and has been alcohol-free since the age of 19. He relocated to Los Angeles and met actors and people in the film industry while working through the Twelve Step program with Alcoholics Anonymous.

Smith began raising funds to make movies and dabbled in talent management, but a mentor advised him to use his network to make venture capital investments outside of the film industry instead.

“It was the best advice I’ve ever been given,” he said.

Smith first focused on cannabis, a thriving industry in which a wave of startups has raised millions in recent years from venture capitalists and made early-stage investments in online retailer Eaze and dispensary chain Harborside.

He didn’t use cannabis at first, but after a girlfriend with lupus and Lyme disease found relief from it, he decided to give it a try and had a “spiritual experience” that pushed him to stop taking pharmaceutical drugs, he said.

Smith fell into a deep depression after discontinuing medications like Adderall and SSRIs, which he had been taking since he was 11 years old. He turned to ketamine, an anesthetic commonly used in human and veterinary medicine as a sedative and painkiller. While ketamine has been shown to be effective in the treatment of some types of treatment-resistant depression, it can also be addictive in some cases.

His mental health didn’t improve until he tried psychedelics, such as Ayahuasca, a plant-derived hallucinogenic drink, and iboga, an African root bark.

“Plant medicine and a clean and healthy lifestyle, including medicine, running, and biohacking, pulled me out of it,” he explained. “And it was the process of deep psychedelic experiences that reset me.”

Smith says psychedelics are in their “fourth wave” and in addition to being a treatment for mental health issues, they can also help solve problems in science and society.

Smith reworked his cannabis-focused VC firm Ultranative into a one-stop shop for psychedelic startups, fueled by his own experience. The company still has a venture capital arm that focuses on early-stage startup investments. However, Ultranative also has an incubation division that builds startups from the ground up, such as Benuvia, an Austin-based cannabinoid and psychedelic drug manufacturing pharmaceutical company.

Ultranative has invested in the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), a pharmaceutical research organization founded by Rick Doblin that will soon have MDMA-assisted psychotherapy approved by the FDA; Heading Health, a Texas-based psychedelic clinic; and Bexson Biomedical, which is developing ketamine treatments for acute and chronic pain.

Smith and Ultranative are far from the only venture capitalists investing in psychedelic startups. While large, institutional VC firms have yet to embrace psychedelics, smaller firms such as PsyMed Ventures, Lionheart Ventures, Iter Investments, and Neo Kuma Ventures have paved the way by directing money to worthy upstarts in the space.

Some have raised millions of dollars in venture capital funding, such as Massachusetts-based Delix Therapeutics, which is developing non-hallucinogenic versions of psychedelic compounds, and Osmind, a software that allows mental-health workers to administer psychedelics and monitor patient outcomes.

Smith says he’s been encouraged by the increase in interest — and innovation — in the industry in the four years that he and his firm have been focusing on it, and compares it to a “fourth wave” following a period of indigenous use, a spiritual awakening in the 1950s-1970s, and an increased focus on how it can be used to treat mental health issues.

“The fourth chapter of this is’solutioning,’ where we’re using psychedelics to enhance creativity and engage in real-world problem-solving,” he explained.