Vintage photos show life before the measles vaccine

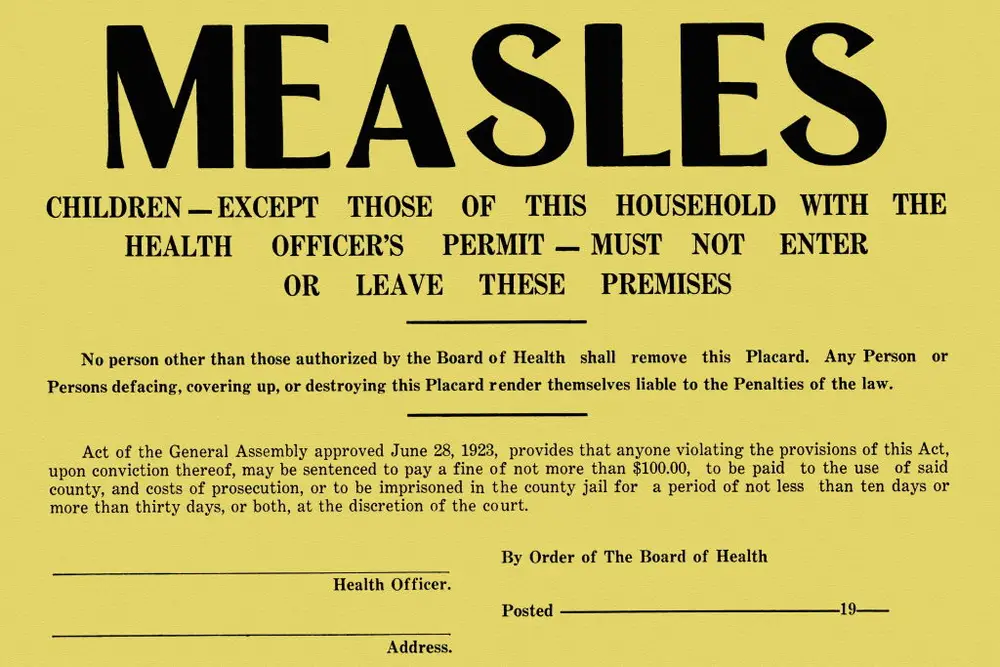

A medical warning notice from 1923.

Before the measles vaccine was developed, over 30 million cases of the disease were reported worldwide each year.

What began as a fever, cough, and rash could develop into complications such as pneumonia or brain swelling, leading to hospitalization or death.

The vaccine became available in 1963, and endemic measles was eliminated in the US by the year 2000. However, outbreaks still occur among unvaccinated populations.

In February, an unvaccinated child in Texas died of measles amid an outbreak of the disease — the first reported measles fatality in the US in nearly a decade.

Here’s a look back at what life was like before the measles vaccine.

Before a measles vaccine existed, the disease was endemic, meaning it was consistently present in specific regions and populations.

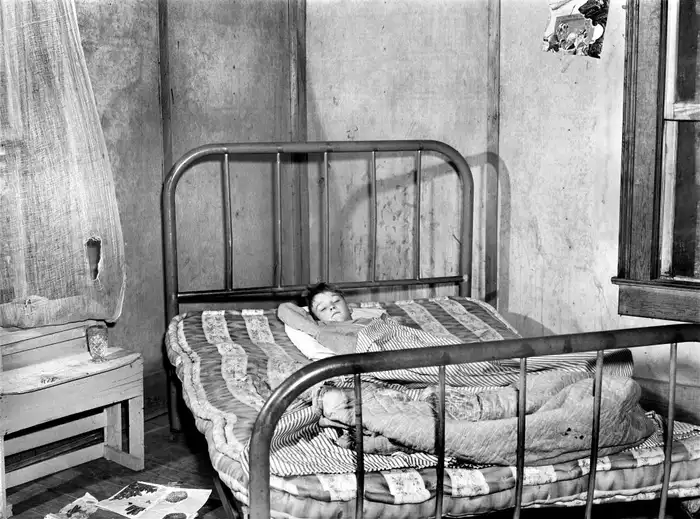

A boy sick with measles in Georgia.

Most children came down with measles by the age of 15, according to the CDC.

A highly contagious disease, measles caused over 2 million deaths globally each year, according to the World Health Organization.

A girl with measles in Chicago.

The mortality rate was higher than whooping cough and scarlet fever, and there was no known cure.

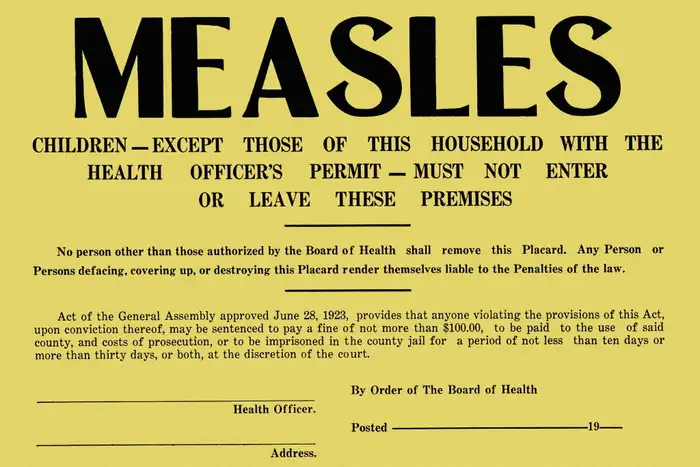

Authorities tried to contain outbreaks by instituting quarantines.

A measles quarantine area in the 1940s.

The quarantines often weren’t strictly enforced, causing epidemics to worsen.

In the US, medical warnings were posted on the doors of some households where residents were infected with measles to prevent further spread.

A medical warning notice from 1923.

Quarantines were more difficult to enforce in lower-income neighborhoods with tenement buildings and multiple families per household.

Measles was so common that it became part of pop culture with portrayals in Hollywood films.

A scene from “Count Your Blessings.”

Characters contracted measles in movies such as the 1959 film “Count Your Blessings.”

All of that changed when John F. Enders developed the first measles vaccine, which became available to the public in 1963.

Hypodermic needles containing new measles vaccines in 1963.

Enders and Thomas C. Peebles isolated the measles virus in the blood of a 13-year-old boy named David Edmonston and developed it into the first measles vaccine, according to the CDC.

In 1968, Maurice Hilleman developed a new measles vaccine that remains in use today.

By 1981, the number of reported measles cases had dropped 80% in the US.

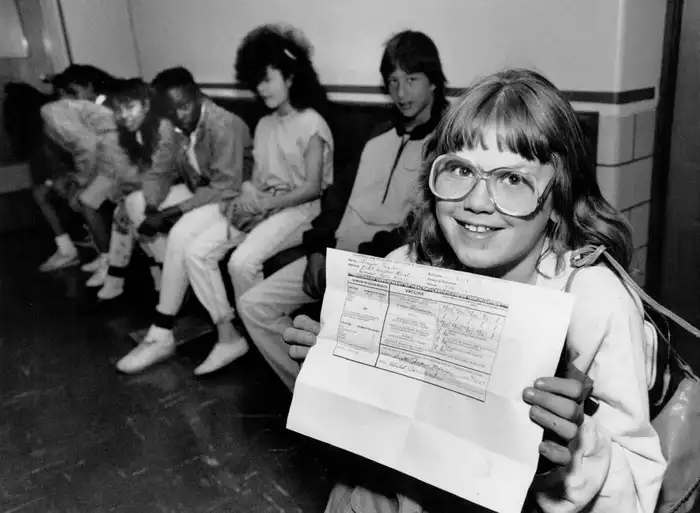

After a resurgence of measles outbreaks in 1989, health officials instituted a second dose of the measles vaccine for children.

A middle school student showed off her immunization record in 1989.

Children are 93% immune after their first dose of the measles vaccine and 97% immune after the second dose.

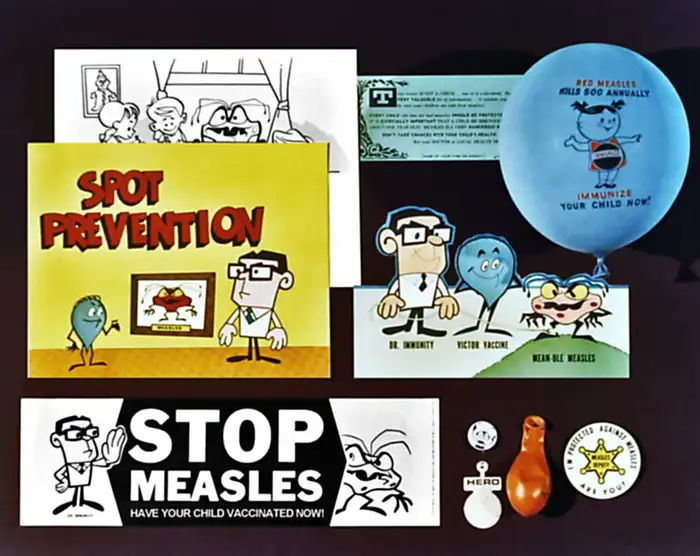

The Centers for Disease Control marketed the vaccine with bumper stickers, buttons, and comic strips in their efforts to eradicate the disease.

Marketing materials promoting the measles vaccine in the US.

Endemic measles was eliminated in the US in 2000, according to the CDC, but anti-vaccine misinformation has gained momentum in recent years. The disease continues to spread among children and adults who are unvaccinated.

In 2019, there were more measles cases in the US than in any year since 1994.

Robert Redfield, then director of the CDC, attributed the outbreaks to widespread vaccine skepticism.

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated,” he said. “Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease the vaccination prevents.”

In February, an ongoing measles outbreak in Texas and New Mexico killed one unvaccinated child and sickened over 130 people, marking the first measles fatality in the US since 2015.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a prominent anti-vaccine figure who was recently confirmed as health secretary of the US, said in a Cabinet meeting Wednesday that “we have measles outbreaks every year” and the situation was “not unusual.”

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.