Why Black men’s job situation is worse than it looks

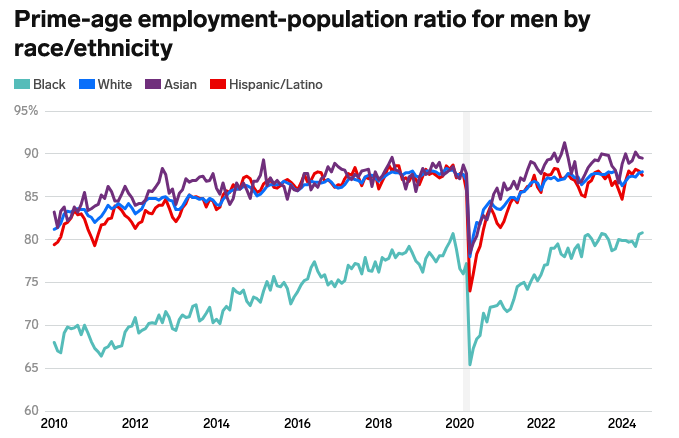

Black men are working at a higher rate than they used to, but they’re still less likely to be working than white, Asian, and Hispanic/Latino men.

If you want to describe Black men’s progress in the labor force, there are arguably two narratives you can choose from.

On the one hand, Black men ages 25 to 54 are working at the highest rate in over two decades: Nearly 81% as of July, the highest since June 1999.

However, there’s also a more pessimistic narrative.

First, though it’s narrowed in the past decade-plus, significant gaps remain between the employment rates of Black men and white, Asian, and Hispanic/Latino men between ages 25 and 54. As of July, each of those three groups had working rates above 87%.

Second, the true picture of Black male employment could be worse than the BLS’s data suggests, Harry Holzer, a labor economist at Georgetown University and former chief economist at the US Department of Labor, told B-17. That’s because a significant number of Black men aren’t being accounted for in employment surveys.

When the BLS calculates employment rates, it only looks at Americans aged 16 and older who aren’t in institutions like prisons or active duty in the military. That means that the tens of thousands of Black men who are incarcerated aren’t being included in these calculations, effectively boosting the Black male employment rate. As of 2017, Black people accounted for 12% of the US population but 33% of the prison population, according to a Pew Research analysis.

Additionally, Holzer said it’s likely that some Black men who aren’t incarcerated or in the military aren’t getting picked up in these household surveys, perhaps because they’re “not officially part of any household, though they might cohabit with family or significant others for periods of time.”

As of July, the BLS estimated a there were 16.2 million US Black men in the noninstitutional population, compared to 18.8 million Black women. Other cohorts tend to have a significantly lower gender disparity, Holzer said.

The bottom line: If the survey data had a more complete picture of Black men, Holzer said the Black male employment rate would likely be “considerably worse.”

“Having these men be missing makes the numbers look even better than they really are,” he said of the Black male employment rate, adding, “We have every reason to believe that if we were counting them, the employment rate would be lower.”

The story of working men in the US is a complicated one. Collectively, men between the ages of 25 and 54 are working at a significantly lower rate than they did in the 1950s — but at nearly the highest rate in the last 15 years. When zooming in on Black men, there’s another complicated story. While the share of working Black men is higher than it was a decade ago, there are still many of them who can’t find jobs or have given up looking — and the employment gap between other groups persists.

Meanwhile, Black women are more likely to be working than white, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino women, which suggests Black men could face a unique set of challenges in the labor market, Valerie Wilson, a labor economist and the director of the Economic Policy Institute’s program on race, ethnicity, and the economy, told B-17.

Holzer and Wilson shared why the employment gap between Black men and other groups persists, what’s driven progress in recent years, and what else can be done in the years to come.

Education differences and discrimination can work against Black men

Education is one factor that can help explain the lower employment rate of Black men, Wilson said.

Generally, people with higher levels of education are less likely to be unemployed, and Black men have lower high school and college graduation rates than white and Asian men.

However, Wilson said that education doesn’t tell the whole story. For example, Black Americans have higher unemployment rates than white Americans even when they have the same level of education.

“Part of the reason why these racial disparities are so persistent is because there is discrimination in the labor market, and the disparity doesn’t get erased by accounting for factors such as education or experience,” she said.

This discrimination can come early in the hiring process. A working paper published in April by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Chicago found that companies were up to 24% more likely to call back applicants with a “distinctively white name” than those with a “distinctively Black name.”

Jared, a Black man in his 30s who was laid off from his data scientist job over a year ago, told BI he’s struggled to find work in his industry. He thinks there are several reasons his search has been challenging, but he believes discrimination has played a role.

“Between finance and tech, most of my interviewers are Asian or white,” he said, adding, “I do feel like there are a lot of prejudices working against me but there’s nothing I can do to change the way the world works.” Jared’s identity is known to BI, but a pseudonym was used due to his concerns about professional repercussions.

Even when Black and white men are raised in homes with the same income and number of parents, Black men go on to earn significantly less on average, according to a study by Harvard and Stanford researchers published in 2018. The study’s authors didn’t find a meaningful earnings gap between Black and white women raised in similar households, which they said suggested Black men face a different set of challenges than Black women when it comes to entering the workforce.

Incarceration and a lack of workforce connections can create additional obstacles to employment

High incarceration rates among Black men aren’t just a factor that makes their employment rate look rosier than the reality. Having a criminal record can make it considerably harder for Black men to find jobs once they return to society, Wilson said.

An analysis published in 2022 by the Prison Policy Initiative, a think tank, found that nearly two-thirds of roughly 50,000 Americans released from federal prison in 2010 weren’t employed four years later. The analysis didn’t focus specifically on Black Americans, but among the formerly incarcerated who found employment, Black and Native American men had the lowest earnings.

In addition to discrimination, the impacts of incarceration, and lower levels of education, Holzer pointed to a few other factors working against some Black men.

A lack of work experience early in life can make it difficult for some Black men to land jobs down the road, he said. Additionally, some young Black men don’t have enough role models and connections in the workforce.

“I think there’s a lot of young Black men coming up who don’t know that many older Black men who are working in good jobs in their families and in their neighborhoods,” Holzer said.

Additionally, Holzer said various factors, including health issues, disabilities, and not being married or having custody of children, could lead to Black men having less capability or motivation to work — these factors also impact white, Asian, and Hispanic/Latino men.

A strong job market and workforce development programs could drive progress

There are several things that might help get more Black men into the workforce.

Both Holzer and Wilson said the tight labor market of recent years — which included record levels of job openings — was arguably the top reason the Black employment rate improved.

“A lot of employers just couldn’t find the people whom they were used to finding,” Holzer said. “When that happens, employers all of a sudden are more open to hiring from groups whom historically they’ve shunned. And I think a lot of Black men are in that category.”

While the job market has slowed over the past year, Wilson said the Federal Reserve’s decisions regarding interest rates will play an important role in ensuring a slowdown doesn’t turn into something worse — making the job market tougher for all Americans.

To boost Black male employment, Holzer and Wilson said policymakers and communities could focus more on helping people with criminal records find work, particularly people with less serious, nonviolent offenses. In recent years, high levels of job openings have made some businesses more open to hiring candidates with criminal records.

Expanding the number of workforce development programs — particularly in industries that have demand for workers like healthcare, IT, and advanced manufacturing — could also spur progress.

“If you can deliver both work experience along with skill building, as you do with apprenticeships or internships, then it’s like killing two birds with one stone,” Holzer said.

Ultimately, Holzer said it’s important to find ways to show Black men that if they stay the course, there’s a real path to them landing a stable, well-paying job.

“I believe these young men, if they saw better opportunities for themselves, they would work harder at building those skills and at getting those early jobs if it didn’t look like a dead end of low-wage jobs forever.”