Why Elon Musk’s push to cut federal waste might succeed where others failed

Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy are promising to tame the federal government. They aren’t the first.

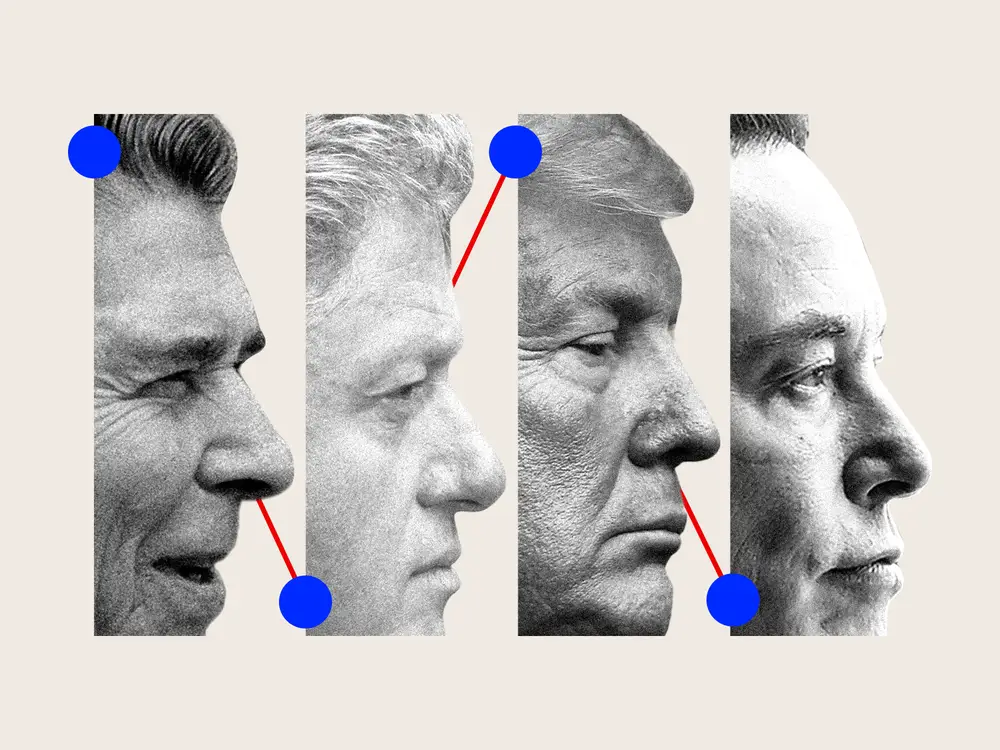

But unlike Reagan and Clinton, who both largely failed attempts at taming federal spending and sprawl, their Department of Government Efficiency has a crucial advantage: Republican control of both chambers of Congress.

That political reality means their ambitious goal of cutting $2 trillion in spending through budget reconciliation could need just 51 Senate votes — and Republicans are projected to hold 52 seats.

Despite its name, Musk and Ramaswamy’s panel, the Department of Government Efficiency, won’t be a government department. Substantial changes to the federal budget would most likely require action from legislators, though Trump transition officials are reportedly looking for ways to short-circuit Congress’ power over spending.

But the two men appear to be well positioned to advise Trump on how to make the deepest cuts to the federal government in generations.

Past presidents have tried to cut the federal budget with mixed success

The federal government isn’t a business. Decisions about which agencies get which money for which purpose and how the money is raised are hashed out in Congress. Lacking the awesome power of a corporate CEO, past presidents, including Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, have struggled to tame the beast.

“There are a lot more restrictions on what you can and can’t do,” said David Walker, a fiscal watchdog who led the Government Accountability Office from 1998 through 2008. “There’s a lot of cultural barriers.”

In 1982, Reagan tasked J. Peter Grace, a chemicals executive, with creating a team of private-sector “bloodhounds” to root through the government, looking for waste and inefficiency.

Two years later, his crew of about 160 senior corporate executives, later known as the Grace Commission, published over 2,000 recommendations they said would save more than $424 billion over three years.

The government’s in-house budget experts, however, didn’t think the changes would be as impactful as the Grace Commission did. Most of the proposals required acts of Congress that never materialized. Some changes, like improving the government’s debt-collection efforts and reducing head count among certain groups of federal employees, were made by the executive branch, bypassing Democrats in Congress.

The nonprofit Citizens Against Government Waste, which carried on the mission of the Grace Commission, said last year that the US government had cut spending by a cumulative total of $2.4 trillion since the 1980s by implementing recommendations from the Grace Commission and from the nonprofit itself. Musk has claimed his committee could cut nearly that much spending in one year.

Clinton took another stab at cutting federal spending and improving government processes with his National Performance Review, which was led and staffed by federal employees instead of the private sector.

The initiative succeeded in shrinking the federal workforce by more than 300,000 workers during Clinton’s term, though the groundwork for some of those reductions was laid under Reagan. But only about a quarter of its proposals that required legislative action managed to clear Congress.

In 1999, the Clinton administration claimed that it had saved $137 billion. The Government Accountability Office said that figure included some double counting and nearly $25 billion that was merely “consistent with” the initiative’s focus on “reinventing government.”

Musk and Trump’s efforts could go further. Trump said the DOGE commission would have until July 4, 2026, to deliver a plan, but Musk said in a post on X that it would “be done much faster.”

What’s different this time

Any proposals from Musk and Ramaswamy that Trump accepts would have a much better chance of getting through Congress than those from Reagan’s or Clinton’s commissions because Republicans are on track to control both chambers of Congress.

Reagan’s and Clinton’s commissions came up against a Congress at least partly controlled by the other party. While contentious bills often can’t clear the Senate because 60 votes are required to overcome the filibuster, many spending-related proposals can pass with a 51-vote majority through a process called budget reconciliation. Republicans are set to hold 52 seats starting next year.

Thomas Schatz, the president of Citizens Against Government Waste, said Trump would likely have at least two opportunities to pass a budget through reconciliation. The fact that Musk and Ramaswamy will have had a two-month head start before Trump is sworn in also helps, he said.

This government-efficiency effort “can be set up faster,” he said. “It depends on how many members the president would like on the commission, and I have no idea. They haven’t asked me. My suggestion is to keep it smaller.”

In the past, Musk has said the Securities and Exchange Commission, which has sued him twice, is “broken” and accused the Federal Aviation Administration of delaying SpaceX launches with “kafkaesque paperwork.”

In recent posts on X, he has floated the idea of rewarding government employees who spend wisely and firing those who waste money. Congress hasn’t figured in recent posts, though in 2022 Musk tweeted that he preferred when the presidency and Congress were controlled by different parties.

In a September appearance on Lex Fridman’s podcast, Ramaswamy outlined a thought experiment for shrinking the federal workforce: Fire all nonelected federal workers whose Social Security numbers end in odd numbers, then fire half of the remaining employees, those whose numbers start with odd digits.

He argued that this arbitrary 75% reduction — about 2.2 million workers — would avoid discrimination lawsuits while barely affecting government services.

Veronique de Rugy, an economist at the libertarian think tank Mercatus Center, has said Musk and Ramaswamy could save $2 trillion if they embraced what many other economists would consider radical reforms. She said that ending aid to states — which the Cato Institute estimated amounted to $697 billion in 2018 and $721 billion in 2019 — could go a long way, as could hacking away at corporate welfare for sectors like pharmaceuticals and electric cars.

But she also expressed skepticism about the Trump administration’s ability to build the bridges that could be necessary for big changes. “They’re going to piss off everyone for stupid reasons,” she said.

There are also third rails of political spending that some are doubtful Trump will be able or eager to tackle, even if Musk and Ramaswamy advised him to do so.

Social Security and Medicare are the two single biggest areas of federal spending, and changing them could be politically unpopular. Trump has generally said he won’t touch them — except for eliminating taxes on Social Security payments, which would mean fewer benefits for retirees in the future.

Earmarks, which allow members of Congress to send money back to their home districts and states, are another significant source of federal waste, and even a GOP-led House and Senate may be leery of getting rid of them.

“The incentive in politics is to make friends,” de Rugy said. Everyone, she added, likes a ribbon-cutting ceremony.