Why the DF-26 is one of the most dangerous missiles in China’s arsenal for the US military

The Pentagon has tracked major growth in China’s arsenal of DF-26s and launchers.

China’s been heavily investing in its missile stockpiles, including one nicknamed the “Guam Express” but also described as a “carrier killer” or “ship killer.”

The versatile DF-26 boasts the range and numbers to hit a variety of targets, from island outposts to American aircraft carriers and warships.

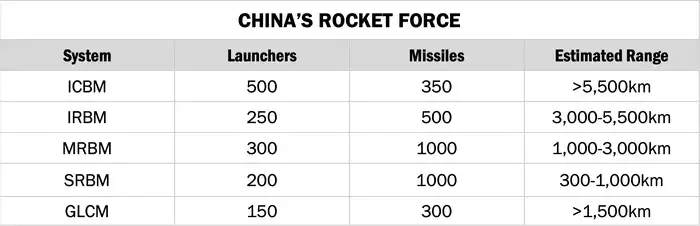

Last fall, the US Department of Defense released its annual report on China’s military growth and developments. It recorded massive growth in the People’s Liberation Army’s Rocket Force, the Chinese military’s missile service, particularly its missile stockpiles.

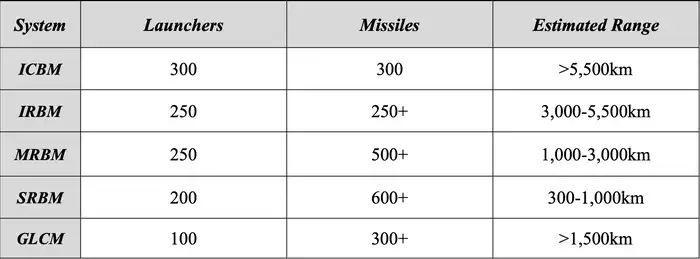

According to the report, China increased the number of intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) like the DF-26 from 300 in 2021 to 500 in 2022 and also increased the number of launchers for such missiles.

2022 estimates on China’s Rocket Force.

2021 estimates on China’s Rocket Force.

The Pentagon said that “the multi-role DF-26 is designed to rapidly swap conventional and nuclear warheads and is capable of conducting precision land-attack and anti-ship strikes in the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the SCS [South China Sea] from mainland China,” pointing to the various ways China could employ the missile in a conflict.

Such a capability could be a major problem for US forces.

What is the DF-26?

China’s DF-26 “carrier killer” missile takes flight in unprecedented test footage.

China’s DF-26 IRBM is a two-stage missile capable of reaching targets out to roughly 4,000 km. The weapon entered service in 2016 after being officially unveiled during China’s 2015 parade commemorating the end of World War II. It is China’s first conventional ballistic missile capable of striking Guam.

It’s a solid-fueled missile, meaning China can launch the DF-26 with little notice. The missile’s most likely target has earned it the nickname “Guam Express.”

The Center for Strategic and International Studies Missile Defense Project suspects China conducted its first operational DF-27 test in early 2017 in the Bohai Sea.

The Chinese military tested four DF-26s in Inner Mongolia, where it regularly conducts missile tests, in July 2017 in a simulated strike against a US THAAD missile defense battery like the US has in South Korea and Guam.

And then in August 2020, China tested the missile in an anti-ship role. The US military said it tested it against a moving target. China has also done night exercises involving relocating the missile batteries in a simulated conflict scenario.

Last month, satellite imagery analysis from Chris Biggers, a GEOINT consultant with Janes, showed an expansion of DF-26 launchers in Beijing. “It remains unclear if new DF-26 launchers will be filling out existing brigades to full strength or if they could represent additional DF-21 replacements,” he said on X.

What makes the DF-26 so dangerous?

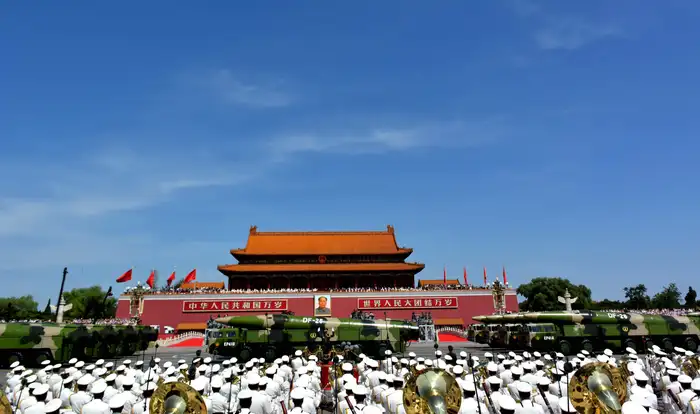

China unveiled the DF-26 at a military parade in 2015.

“It’s a potent threat,” J. Michael Dahm, a senior resident fellow for Aerospace and China Studies at the Mitchell Institute, told B-17, adding, “It is an increase in the numbers of missiles that have this greater range.” But, Dahm noted, the DF-26s are also replacing many older models of missiles that have the same mission.

Big concerns with the DF-26 is which US targets it can strike and the threat to American warships, including high-profile assets like aircraft carriers. China can also swap the payload from conventional to nuclear warheads.

After the Department of Defense released updated numbers for the DF-26 last fall, Tom Shugart, a former US Navy submarine commander who’s now an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security think tank, said the increase gives China the ability to pursue more than just top targets.

The notable increase in the size of the stockpile effectively makes the DF-26s not just “carrier killers” but, more broadly, “ship killers.” He said on X in fall 2023 that “if each DF-26 launcher had just one reload, we could be facing 400+ missiles. Well, here we are…”

And there’s evidence China has been practicing for such an engagement. In November 2021, satellite images showed apparent full-scale outlines of US Navy aircraft carriers in the Ruoqiang area of Xinjiang’s Taklamakan desert in northwestern China. Satellite images have also spotted mock-ups of American destroyers and big-deck amphibious assault ships.

Naval power is a cornerstone of American military might, but the DF-26 threatens that, among various other targets.

How can the US counter the DF-26 threat?

The aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson transits the Pacific Ocean.

US lawmakers have raised concerns with the Air Force and Navy secretaries about the vulnerability of American bases in the Pacific to Chinese missile barrages, and officials have indicated a need to significantly bolster American air defenses to counter a potential Chinese missile attack.

Experts have emphasized a need to harden air bases to survive such an attack, which could be unlike anything seen previously, and disperse forces to make it difficult to crush US airpower in a single blow. Chinese military doctrine emphasizes surprise, and some experts have said a strike could include ballistic and cruise missiles, possibly drones, in waves to overwhelm air defenses.

There’s no guarantee China uses its DF-26s. Maybe it goes for a range of targets, or maybe it goes after a few specific targets. Maybe it holds them in reserve rather than using them in the opening salvos. There’s a lot of unknowns.

“The threat from the PLA’s large and growing arsenal of long-range precision strike weapons against air bases is serious, but not unsurmountable,” Dahm wrote in a Mitchell Institute paper this past July. “There are practical, physical limits on the number of sophisticated weapons an adversary like the PLA may launch against dozens of established and dispersed air bases at any one time.”

That said, growing missile stockpiles and increases in the number of launchers give the Chinese military greater flexibility, offering more options in a conflict.