Why the West’s vital undersea cables are so vulnerable to attack

Warship off the coast of Latvia during international naval exercises in 2023.

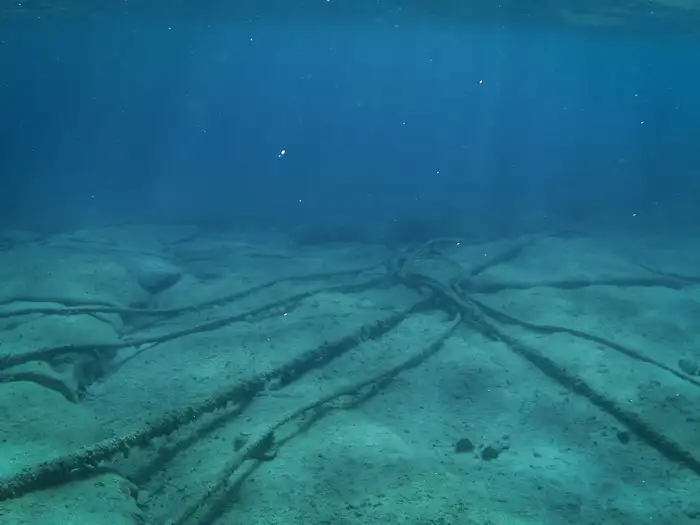

The vast networks of data cables that crisscross our world’s oceans are crucial for almost every aspect of modern life.

The cables span around 745,000 miles and are responsible for transmitting 95% of international data. Around $10 trillion in financial transactions travel across these networks each day.

Despite their importance, events this week have highlighted just how vulnerable the West’s internet subsea cables are to attacks from hostile powers.

Geopolitical tensions, a lack of clear ownership, and outdated efforts to protect the infrastructure have all led to fears that they could be intentionally damaged by the likes of Russia or China, creating social and economic chaos.

Cuts to cables in the Baltic Sea

On Sunday and Monday, cables under the Baltic Sea carrying data between Germany and Finland and Sweden and Lithuania were severed in what German Foreign Minister Boris Pistorius described as a likely act of sabotage.

In a joint statement, Germany and Finland’s foreign ministries connected the incidents to Russia’s “hybrid warfare” campaign to undermine the West in the fallout from the Ukraine war.

Meanwhile, Sweden is investigating the sighting of a Chinese vessel near the cables, The Financial Times reported.

Experts say that as the West has come to rely on the cables as a crucial part of its infrastructure, efforts to safeguard them have not kept pace.

“The attack surface is vast (there is a LOT) of cable, and we do not have sufficient subsea situational awareness to enable monitoring,” Gregory Falco, an Assistant Professor at the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Cornell University, told B-17.

A Russian submarine takes part in exercises off the Russian coast near Vladivostok in 2022

Vulnerable to attack

One factor is the complex ownership and maintenance structure of cable networks. The cables are privately owned by telecommunications companies, which are responsible for their security and repairs.

They are monitored using an Automated Identification System that identifies if a ship — possibly a hostile vessel — is nearby.

Falco described the system as “antiquated.”

“The reality is that any ship can turn off their AIS transponder,” said Falco, thus evading detection.

Unlike Russia, whose internet cables mostly run overland, the cables Western countries rely on are deep under the sea — and it’s an asymmetrical vulnerability Russia is signaling it could exploit.

“Russia is not as dependent on subsea cables for internet as Western Europe, so can easily attack them without major damage to its own communications infrastructure,” said Erin Murphy deputy director of Chair on India and Emerging Asia Economics at the CSIS in Washington, DC, and coauthor of a recent report on the threat to the cables.

B-17 reported in September that the General Staff Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research, a Russian naval unit specializing in sabotage, had been surveilling the cables.

The unit operates a small fleet of deep-sea submarines capable of operating at a depth of around 2,500 meters and a surveillance vessel, the Yantar.

Sidharth Kaushal, an analyst at London’s RUSI think tank, told B-17 at the time that because the West is not officially at war with Russia, it can do little if a Russian vessel is detected in international waters near the cables.

There is also the prospect of China teaming up with Russia on an attack, said Murphy, amid reports on the presence of the Chinese vessel near the cables.

“There have been questions about China’s support or lack of opposition to Russia’s war in Ukraine but if intentional, this is an aggressive step by a China that typically operates in the Indo-Pacific region,” she said.

The latest incident has not been confirmed as a case of sabotage. The Kremin and Chinese embassy in London did not immediately respond to requests by B-17 for comment.

Whether cut by accidents or in a hybrid warfare attack, the logistics of repairing the cables can be formidable.

“There’s only so many trusted cable repair ships and the repairs can take time, depending on the extent of the damage and the conditions at sea for the ships to navigate,” Murphy told B-17.

“If the cut has been made in hostile waters, security issues will become a major risk for cable repair ships or those ships navigating those waters to protect cables.”

Fiber optic cables on the floor of the Mediterranean Sea.

No backup plan

The cable severances in the Baltic this week didn’t result in an internet blackout — just lower bandwidth and disruptions for individual users.

That’s because companies usually have the capacity to re-route data through alternative cables if one or more are damaged,

“The network infrastructure is built in such a way that, on a larger scale, the fault in a single submarine cable has no major effect, although it may have effects on a single operator or individual,” Henri Kronlund, a spokesman for Cinia, the company that operates the damaged Germany-Finland C-Lion cable, told B-17.

Russia, however, retains the capacity to totally cut off internet connections to countries by cutting several cables in coordination, said Falco.

“It’s practical for the Russians to have visibility to the various paths that data can take and cut each cable in concert. This is particularly easier for countries with less cable connections like Iceland,” he said.

In response to the threat, Western countries are trying to better protect existing cable networks or route data through satellites if they are disrupted.

In the CSIS report in August, Murphy and other analysts called for the US to strengthen international coordination and enhance resources to protect existing undersea cable networks.

But until there’s a backup in place, the undersea networks will continue to be a weak spot Russia can menace in its escalating confrontation with the West.

“The scale and exposure of undersea infrastructure also make it an easy target for saboteurs operating in the gray zone of “deniable attacks short of war,” the CSIS noted in its report.