Young Americans are going country, reversing a decadeslong trend of moving to cities

Millennials and Gen Zers are moving to more rural areas in droves.

Chase Voss, 36, moved this year from Hawaii to rural Georgia to be closer to family.

His new home, Dawson County, is one of the fastest-growing counties in the US for young people, amid a wave of movers into rural areas that’s reversing a decadeslong trend toward cities.

Voss, a real-estate agent, said many younger and middle-aged families have moved to Dawsonville from out of state for job reasons. Though there aren’t many jobs in Dawsonville itself, which has a population of just over 4,600, some work tourism or nature jobs in the nearby mountains, while others commute the over 50 miles to Atlanta or work remotely.

“Dawsonville is far enough away where they can feel that remoteness but still close enough to the city that they can have access to everything,” Voss said.

Chase Voss moved to Dawson County, Georgia, from Hawaii.

In recent years, younger professionals have been bucking a longtime trend of their age group: moving to cities. Now, with flexible work arrangements and high housing costs, many are forgoing more densely populated areas in favor of rural America. Those areas bring bigger houses, lower prices, and a different pace of life — and their own new challenges.

Where younger people are moving

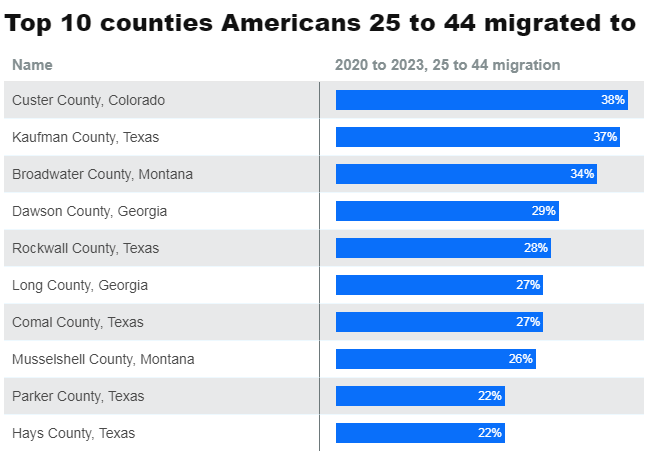

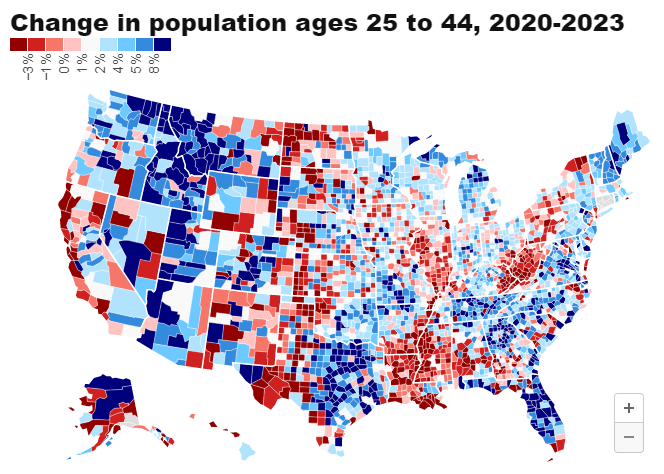

A recent analysis of Census data by Hamilton Lombard, a demographer at the University of Virginia, found that 63% of rural counties or counties in small metros experienced increases in their populations of 25- to 44-year-olds between 2020 and 2023, compared to 27% between 2010 and 2013.

Northern Georgia, the Mountain West, and New England were rural regions with particularly strong population growth among young Americans. The 10 counties that saw the biggest influxes of younger adults were largely rural; the most populated of all of those areas is Hays County, Texas, in the suburbs of Austin, which had a population of around 280,500 in 2023. Musselshell County, which is the least populous, had just 5,308 people as of 2023.

That’s a big shift from pre-pandemic patterns: From 1980 to 2020, white-collar workers increasingly moved into densely populated areas, per Lombard’s analysis. That trend was expected to continue — until the pandemic and the rise of remote work. Since 2020, Lombard found, rural areas and smaller cities have attracted that younger workforce at the highest rate in nearly a century.

Jeannie Steele, a real-estate broker in Townsend, Montana, has seen an influx of young people. Broadwater County, with about 8,000 residents, was the third-fastest-growing county for Americans ages 25 to 44, Lombard’s analysis found. Townsend is located about 30 miles from Helena, though Steele said many commute to Bozeman or Three Forks.

Steele said she previously considered her area a retirement hub. However, the construction of a new elementary school starting in 2019 brought many younger families, particularly some working in construction, mining, or medicine. Many are moving from Washington, California, and Minnesota, Steele said.

“We have a lot of people here that come and have this vision of homesteading,” Steele said. “They want to grow their own food. They want to have chickens and gardens. Interestingly enough, though, all those things in our environment are difficult.”

In Custer County, Colorado — the area that’s seen the highest net percent increase of 25 to 44-year-olds — 28-year-old Arrott Smith has seen many more nice cars driving around as younger, well-off remote workers move into town.

“For the most part, that’s kind of a weird juxtaposition because it is a very working-class county,” Smith said.

Smith, the manager and a roaster at local haunt Peregrine Coffee, said that the area has traditionally skewed older — but saw a big influx of younger workers over the last few years. Smith said that the area’s newer residents are buying homes even as costs have gone up.

“To me it’s more like the people that are moving here have a romanticized version of what it is to live up here,” Smith said.

Going rural can be challenging

Economist Jed Kolko said that, with the proliferation of remote work, Americans moved out of bigger urban areas into nearby suburbs or smaller towns. But headwinds in some occupations might slow down the influx of newcomers.

“If unemployment rises, particularly in the kinds of occupations where remote work is more common, employers might be more able to insist on workers spending more days in the office,” Kolko said. “Even if that doesn’t cause people to reverse the moves that they made during or after the pandemic, it could still slow down that trend in the future.”

Meanwhile, in areas that have seen a rush of new residents like Townsend, Kolko said it’s key for housing to keep up with demand. If not, affordability challenges from big cities could spread out.

New challenges confront the residents reshaping these areas. Steele said many people moved to her part of Montana after the TV series “Yellowstone” aired, though she’s seen many younger people regret their moves. She said many don’t anticipate the challenges of living in a more remote part of the US, such as navigating storms, buying goods in bulk, or dealing with isolation.

Recently, rentals have gone really fast, Steele said, adding that rents, on average, have increased from about $750 in 2019 to well over $1,000 monthly. A more stark comparison is some of the county’s single-family homes, many of which were built in the late 1970s and early 1980s; while they sold for about $100,000 in 2017, they range from $390,000 to $400,000 today, Steele said.

Housing affordability pushed Solitaire Miles, a Gen X musician, to move from Chicago to northwestern Indiana in 2013. Miles and her husband lived in the Chicago area for about 13 years. While they were gainfully employed, she said, they weren’t earning enough to live comfortably while renting. They couldn’t afford a home in Illinois, especially with high property taxes. But in Indiana, they found a home with three-quarters of an acre of land just 50 miles from Chicago for under $200,000.

Miles loves having the space. A quieter pace of living has helped stimulate her creativity and her at-home border collie rescue — they currently have five of their own dogs.

Solitaire Miles and dogs.

But the area has changed over the past few years; the pandemic also fractured her community.

“After Covid, everything just kind of went downhill. So many people died, a lot of elderly died, or they left and they moved south,” Miles said.

She’s glad they ended up buying out there, and if and when they choose to sell, they’ll make a tidy profit. Even so, though, the move came with its own struggles.

“It was hard. I had the gym that I loved and the spas and my beauty salon and the restaurants — all of our friends,” she said. “I mean, I did make friends here, but it took time, and I had to go to places where I knew they would be.”

For Voss, the real-estate agent, it took him time to acclimate to the South. As a gay man, he noticed more hostility toward his community, though he said many in Dawsonville have appreciated his advocacy work. He’s enjoying rural Georgia for the time being but anticipates splitting his time with Hawaii in a few years.

“Georgia is beautiful, I love it. It’s so great for so many people,” Voss said. “But for me, because of the mentality of the people here, I just don’t see myself staying full-time.”