Sharpening focus on crime, Oakland reverses major cuts to violence prevention

Newfound money will rescue the Department of Violence Prevention. What comes next?

OAKLAND, Calif. — Reduced funding for the Department of Violence Prevention drew the most public outcry of all the budget cuts approved this year by Oakland’s leaders amid a deficit described as the city’s worst ever.

However, in a climate of high tensions surrounding local crime, the city dug up a solution from the couch cushions this week, saving the department from an anticipated squeeze on the roughly two dozen nonprofits to which it outsources work.

The City Council unanimously approved a combined $28 million from a parcel tax and the general purpose fund late Tuesday night, allowing the nonprofits to continue working on core social problems that lead to gun and gender-based violence. This year, Oakland police had investigated 91 deaths as homicides as of Friday.

The funds will save the council from budget cuts that have sparked outrage among residents who have directly benefited from programs related to the city’s violence prevention efforts. Violent crime increased during the pandemic and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels — though it appears to be easing.

However, there is one catch: the parcel tax for violence prevention secured by a 2014 ballot measure expires next year. Unless voters approve a similar measure next November, the lifeboat for those external nonprofits will sink in the long run.

“These grants do have an expiration date, and we need to be very proactive in doing the fundraising well in advance of approving our budgets so that we can… hopefully expand these programs,” Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas said at Tuesday’s meeting.

The department will also discontinue a $1.4 million program that provided mini-grants to other community nonprofits that provide services — money that will almost certainly have to be replaced through donor fundraising.

Nonetheless, Tuesday’s meeting provided a brief respite from what has felt like a political hot potato in Oakland this year: the question of how to reduce violent crime and whether the city has done enough.

Last year, Oakland police investigated 120 deaths as homicides, a rate that roughly matches the rate so far in 2023.

It was a decrease from 121 cases in 2021, but it was still higher than 109 in 2020 and 78 in 2019 — the latter figure reflecting how much worse violent crime became when the pandemic hit.

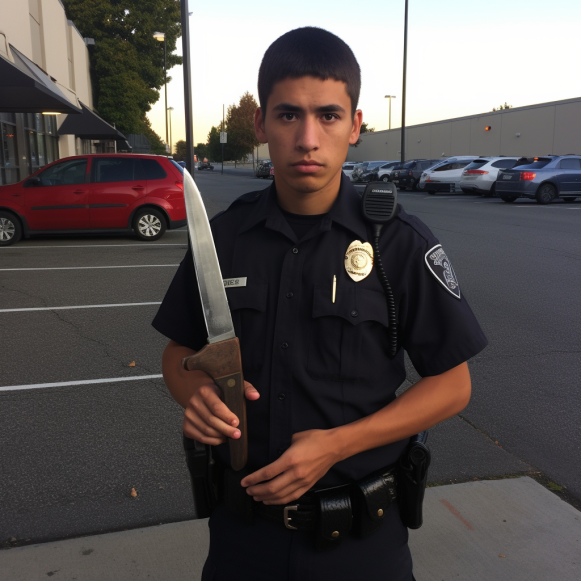

While the city’s underfunding of the Department of Violence Prevention was the most contentious budget cut this year, much of the focus on crime reduction has been on law enforcement.

Residents and out-of-towners flocked to an East Oakland neighborhood earlier this month for a rally hosted by Neighbors Together, an anti-crime organization best known for its green lawn signs and aggressively pro-police messaging.

Meanwhile, city councilmembers held town halls throughout the summer to gauge public opinion on crime — events that occasionally came to a halt when individual speakers began shouting at the hosts.

On Tuesday, the City Hall council chamber was similarly packed. However, the voices that received the most applause had little to do with policing.

They came instead from teenagers and young adults who came up through Youth Empowerment Partnership, a local agency that receives department funding, and the young speakers who described how they were rescued from the familiar trappings of poverty: gang violence, sex trafficking, and drug use.

“When you look at me, you might think I’m someone who has their act together. Remember, I was a drug addict for many years and had mental issues — and I still do,” said Carmel Desiree-Ewing, a 21-year-old Oakland resident. “I have gained strength, growth, and resilience as a result of this program.” I was able to complete high school and, on top of that, graduate as valedictorian… all thanks to the funding you provided for the YEP system.”

Marshaun Farris, an adult counselor at the agency, observed that the teenagers appeared to be in “cocoons” when he first started working with them, but they gradually gained enough confidence to speak about their experiences in such a public setting.

“My family has also been victimized by this community,” Farris explained. “My son was shot in the head in front of McClymonds (High School).” He was in Highland Hospital for three days, and all I could think about was whether he was going to be okay and what I needed to get back to with these kids at work… because I’m passionate about what I do with these kids.”

In addition to the $28 million in grant funding, the council announced new initiatives to evaluate some of the core issues associated with the city’s crime problem, such as its frequently flaky 911 system.

Mayor Sheng Thao announced earlier this month that the city would invest $2.5 million in revenue generated by the Oakland Coliseum site in improving 911 response times, following a warning from California officials that the city needed to step up this year.

It was another example of Oakland’s leadership finding just enough money to keep things moving despite a structural deficit.

“We all had to shoulder the responsibility of balancing the city’s budget,” Kentrell Killens, Director of Violence Prevention, said. “And we’re a strong, young department with high expectations, so any potential service cuts would have had a significant impact.”