Larry Magid: Polly Klaas tragedy changed how we look for missing children

New book chronicles events from 1993 kidnapping and murder

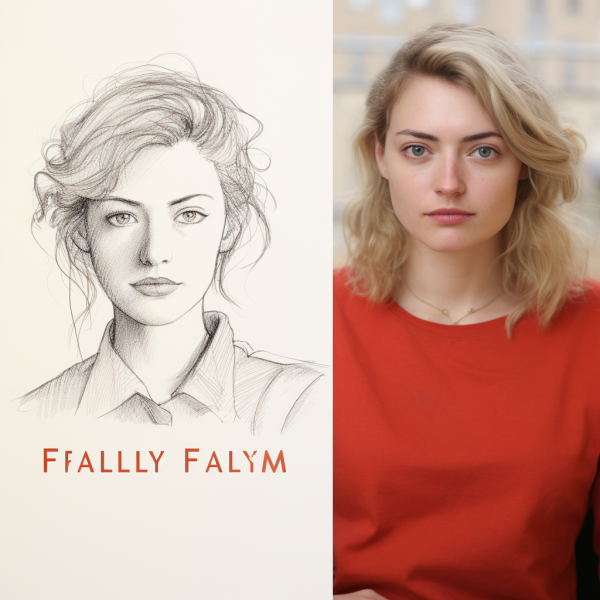

Polly Klaas, 12, was abducted from her home in Petaluma on October 1, 1993, while having a sleepover with two friends. She was discovered dead more than two months later, following a massive local search and intense national publicity, including a segment on America’s Most Wanted and articles in Time, the Associated Press, and numerous other news outlets.

The entire episode is documented in best-selling author Kim Cross’s new book, In Light of All Darkness, which covers the crime, the investigation, the aftermath, and the efforts of hundreds of volunteers in and around Petaluma.

Digital posters for missing children

Even though I never met Polly Klaas, this case became personal to me.

I was driving south on 101 from my house in Redwood City to the offices of Netcom, an early internet service provider that was going to show me the first internet browser, Mosaic, for a book I was writing called Cruising Online: Larry Magid’s Guide to the New Digital Highways. My car radio was tuned to a news station reporting on Polly’s case. Someone suggested that listeners drive to Petaluma to aid in the search. I began to cry as I remembered Polly and my own children. My first instinct was to cancel my meeting, turn around, and drive the 80 miles or so to Petaluma to distribute Polly’s missing child poster. But, as I approached the freeway exit, it occurred to me that I didn’t need to drive all the way to Petaluma to assist. I could post posters on the internet.

When I arrived at Netcom, I saw the new Mosaic browser, but I also had the opportunity to speak with their staff about getting Polly’s image on the nascent public internet, which was dwarfed at the time by the number of people using AOL, Prodigy, CompuServe, and free online bulletin boards. Because all three of those major online services carried my syndicated newspaper column, I had the contacts I needed to convince them to prominently share Polly’s missing child poster. I also contacted The Bay Area Bulletin Board Advisor (BABBA), who distributed the poster on several bulletin board systems in the Bay Area. I was not acting alone. Gary French and Bill Rhodes, volunteers on the ground in Petaluma, helped me by emailing me the images and files I needed to upload to these services.

Requests from other families

It was also my first stint as a Mercury News tech columnist, and my October 10, 1993, column was titled “Online services unite to help find abducted girl,” and it included instructions on how to download Polly’s poster. A few weeks later, Time Magazine ran an article titled “High-Tech Dragnet” about “a novel use of the information highway.” After the Time article was published, I began receiving calls from relatives of missing children all over the country pleading for assistance. That’s when I realized I was in over my head. The distribution of Polly’s poster was a one-time event. Doing this on a national scale required resources and expertise that I lacked. That prompted me to contact Ernie Allen, president of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), the congressionally mandated national clearinghouse for finding missing children and protecting children from sexual exploitation. Allen agreed to take on the responsibility of online distribution of missing child posters, resulting in NCMEC’s collaboration with these online services and the creation of MissingKids.org, which had 8.1 million visitors in 2022 in addition to NCMEC’s extensive social media outreach.

Influence on my life

It also had a significant impact on my life, as Kim Cross documents in her book. I ended up on the board of NCMEC, where I served for over 20 years. A year after Polly’s kidnapping, NCMEC asked me to write “Child Safety on the Information Highway,” which resulted in the creation of SafeKids.com, SafeTeens.com, and ConnectSafely.org, the non-profit internet safety organization of which I am the CEO.

My story takes up only two pages of Cross’ excellent 431-page book, which tells many stories about how volunteers, local cops, the FBI, forensic artists, lie detector specialists, celebrities, and others from all over the country worked around the clock to help find Polly until we received the heartbreaking news that she had been found dead. Cross chronicles the day Polly’s body was discovered, the trial of her murderer, and the ongoing aftermath, including the establishment and operation of the Polly Klaas Foundation and the impact of this case on law enforcement practices worldwide. Cross’s book is the definitive chronicle of this tragic and historic event, as well as broader issues of child safety, such as the media’s proclivity to focus on cases involving pretty white girls and the underreporting of crimes against children of color. It is meticulously researched and includes first-hand reports from those involved.

America Weeps

“America Cries,” one of the final chapters, is about the day Polly’s father, Marc Klaas, announced, “My beautiful child is dead.” “America’s child is no longer alive.” It brought tears to my eyes at the time, and again as I read Cross’s book and relived this tragic moment. However, along with the chapters on Polly’s Legacy and the Epilogue, it reminded me that Polly Klaas’ tragic death prompted changes in the way law enforcement and nonprofits such as the Polly Klaas Foundation and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children are now better able to help find missing children and prevent kidnapping and exploitation.