UC Berkeley scholar faces renewed calls to resign over false Native American identity claims

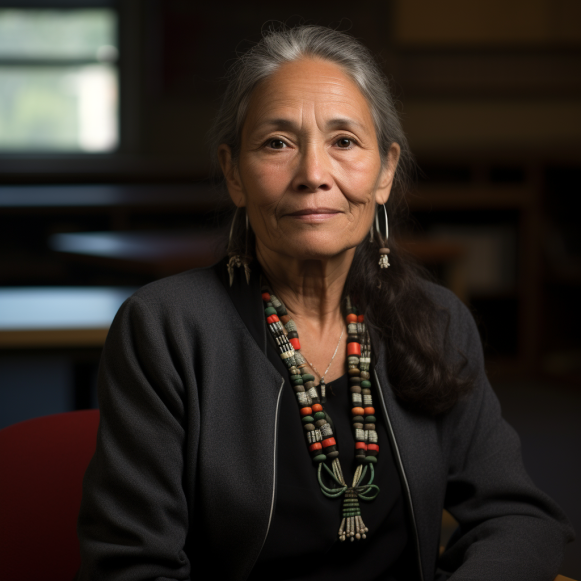

Anthropologist Elizabeth Hoover admitted in May that she is ‘a White person’

UC Berkeley students and Native American scholars have renewed calls for anthropologist Elizabeth Hoover’s resignation, after she publicly admitted in May that she is “a White person who has incorrectly identified as Native my entire life.”

The calls for Hoover to leave UC Berkeley, or for the university to take action, resurfaced this month with the retirement announcement of Andrea Smith, a controversial UC Riverside ethnic studies professor who faced accusations for at least 15 years that she helped build her career and scholarship on false claims of Cherokee ancestry.

UC Riverside professor resigns over ‘pretendian’ claims, but will continue to teach for another year

Last week, a separation agreement between UC Riverside and Smith was revealed, and students and scholars say it represents progress in the thorny issue of how universities respond to tenured faculty who have been accused of falsely representing themselves as Native Americans in order to win prestigious positions, funding, and research and publishing opportunities.

These cases have gained prominence in recent years as a result of heated debates in Native American circles about high-profile “Pretendians” and the complexities of Native identity.

“I applaud UC Riverside for taking this issue seriously,” said Ataya Cesspooch, a doctoral student in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at UC Berkeley. Hoover is a tenured faculty member in the department, where she specializes in Native American environmental health and food justice. “Riverside has demonstrated that it is entirely within the university’s power to remove tenured professors for fraudulent identity claims.”

The UC Riverside agreement with Smith came in response to a complaint filed by 13 of her faculty colleagues in August 2022, alleging that she violated Faculty Code of Conduct provisions regarding academy integrity. A year earlier, Smith was the subject of a lengthy New York Times magazine investigation into ethnic fraud allegations, and she was dubbed “the Native American Rachel Dolezal” in a 2015 Daily Beast report.

The agreement allows Smith, who “denies and disputes” the allegations leveled against her, to continue working as a teacher for another year. She will also be able to retire with an emerita title, benefits, and a pension, and she will not be subjected to a formal UC Riverside investigation. According to university spokesperson John D. Warren, the agreement brings the case to a “timely conclusion,” as “investigations of a tenured faculty member for alleged misconduct have the potential for litigation and appeals, and can unfold over the course of years.”

While scholars and students are disappointed that the agreement gives Smith a “soft exit,” they say it still provides a roadmap for how UC Berkeley could deal with the Hoover scandal.

“Berkeley should pay attention, follow suit, and improve upon this,” said Audra Simpson, an anthropology professor at Columbia and a Mohawk scholar. “If a scholar has been found to violate the tenets of research ethics or has otherwise demonstrated that they lack academic integrity, there should be a formal complaint, a full investigation, and if found in violation, they should be dismissed.”

Last November, Cesspooch and two other Native American PhD students, Sierra Edd and Breylan Martin, issued a public statement calling for Hoover’s resignation. More than 390 people signed the statement, which included other Native American scholars and activists, as well as current and former students from UC Berkeley and Brown, Hoover’s post-graduate alma mater.

For the majority of her career, dating back to the 2000s, Hoover claimed to be descended from the Mohawk and Mi’kmaq peoples of eastern Canada and the United States. She mentioned her ancestors in news reports and while working on her doctoral dissertation for Brown University. Meanwhile, she received jobs, grants, and two prestigious Ford Foundation fellowships for people from underrepresented groups. According to the news site Indianz.com, she published books and papers and became a mover and shaker in the “food sovereignty” movement.

Hoover admitted in May that she is not descended from either tribe and apologized for “the harm” she caused friends, colleagues, and students by falsely claiming to be. According to a statement on her website and an interview with this news organization, she always assumed she was Native American because that’s what she was told growing up in upstate New York. She claimed she had never knowingly lied about her identity or attempted to deceive anyone. “I’m a human,” she explained. “I didn’t set out to hurt or exploit anyone.”

Hoover did not respond to emails or phone calls requesting her reaction to Smith’s retirement or renewed calls for her resignation. In May, she stated that she had no intention of resigning, and UC Berkeley previously stated that it has no plans to remove Hoover from her position, with spokesperson Janet Gilmore stating that the campus supported her efforts to address “the extent to which this matter has caused harm and upset among members of our community.”

In a statement this week, Gilmore declined to comment on Smith or Hoover in particular, and said the campus typically does not comment on faculty misconduct allegations unless a violation is found. However, “speaking generally,” Gilmore stated, “I can tell you that when and if any allegations of policy violation are brought to our attention, we review the concern and take appropriate action.”

Given the sensitivity of personnel matters, it’s unclear why the faculty complaints against Smith finally prompted UC Riverside to negotiate her departure after years of controversy. While Edd confirmed that she, Cesspooch, and Martin did not file a formal complaint, Cesspooch claimed that in response to their public statement, Berkeley’s chancellor and administrators took no action, “signaling their indifference to an issue that threatens the validity of indigenous studies at Berkeley and beyond.”

Hoover’s apology had previously been dismissed by the students as an attempt to elicit “pity” and as failing to address her multiple instances of “misconduct.” Misrepresenting herself as Native American on grant and job applications, for example, is alleged to have “robbed Indigenous scholars of these opportunities.” Hoover admitted to lying about herself during research projects, such as when she embedded herself in the Akwesasne Mohawk community in Northern New York for her dissertation on residents’ perspectives on health and the environment.

Native American scholars have also rejected Hoover’s explanation that she relied on family “lore” to support her belief that she was Mohawk and Mi’kmaq, claiming that it was her responsibility to use professional research skills to confirm her ties to these tribes.

Scholars say the cases of Hoover and Smith demonstrate some of the reasons universities are hesitant to investigate faculty accused of ethnic fraud. For starters, administrators must embrace what it means to be Native American, which isn’t simply a matter of someone self-identifying as such, according to Wesley Leonard, a UC Riverside associate professor of ethnic studies who signed the complaint against Smith. People must instead be enrolled in a tribe, which is equivalent to being a citizen of a sovereign nation, or show a strong family connection to a tribe and “be claimed by the community,” according to Leonard, a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

According to Wesleyan American Studies professor J. Kehaulani Kauanui, a former friend of Smith’s from UC Santa Cruz who long urged her to come clean about not being Cherokee, ethnic fraud cannot technically be a violation because universities must also abide by federal laws that prohibit consideration of race and ethnicity in hiring, promotion, and firing decisions. However, Kauanui explained that when scholars misrepresent themselves in their research work, it is still considered academic misconduct.

For these reasons, Hoover’s “enduring presence” at Berkeley is a problem, according to Martin, one of the graduate students, who adds, “Promoting this lack of research integrity by continuing to compensate her for her ethnic fraud will inevitably lead to a breakdown of Berkeley’s reputation and trustworthiness, something we can’t afford if we want to foster indigenous excellence in our communities and scholarship.”