Skelton: How a racist housing policy caused a bitter California brawl

60 years ago, the Rumsford Act turned into a historic civil rights triumph in the state

We recently celebrated the 60th anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington. There was no mention of the 60th anniversary of a historic civil rights victory in California.

That’s completely understandable. Few people are likely to be aware of the Rumford Fair Housing Act, which resulted in arguably the largest and most bitter brawl ever witnessed in California’s Capitol.

Looking back, it’s difficult to imagine what the fight was about. It was a debate over whether it was legal — let alone moral — for homeowners and landlords to continue discriminating against people of color in the sale and rental of housing.

Following much debate and prodding from Democratic Gov. Pat Brown, the Democratic-controlled Legislature voted to prohibit racial discrimination in housing. The public outpouring of rage was swift. The following year, Californians voted nearly 2 to 1 to legalize discrimination once more. However, the state and federal Supreme Courts eventually ruled that the voters’ action was unconstitutional.

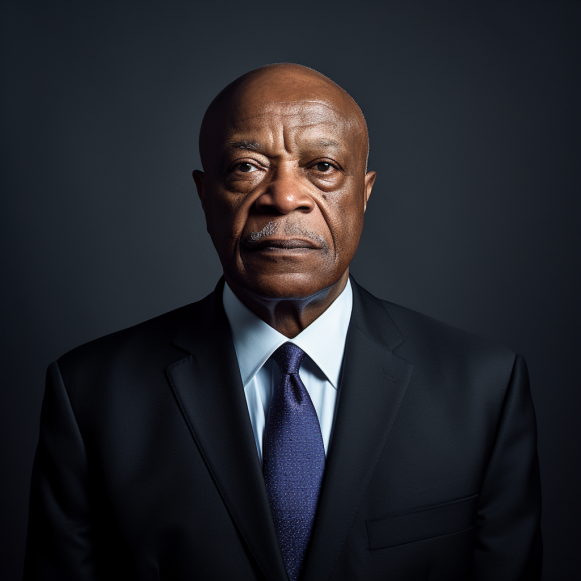

“The mood in California was as anti-equality — by legislative edict and local ordinances — as you can imagine,” recalls legendary Black politician Willie Brown, former Assembly Speaker and San Francisco Mayor.

“The Rumford Act was considered a no-no.”

In 1963, the mood in America was bleak.

Police Chief Bull Connor of Birmingham, Alabama, unleashed dogs and fire hoses on civil rights marchers. Alabama Governor George Wallace stood in front of the schoolhouse door, vowing to prevent integration. Medgar Evers, a civil rights leader, was assassinated in Mississippi. Racists detonated a bomb in a Birmingham church, killing four young girls.

Gov. Brown boldly proposed legislation in Sacramento to end racial discrimination in housing. “No man should be denied the right to own a home because of the color of his skin,” the governor declared.

In the mid-1960s, those were combative words.

California, unlike the Jim Crow South, did not have officially segregated schools or drinking fountains for white and black people. However, de facto housing segregation was widespread. Local covenants barred people of color from many white neighborhoods.

The housing bill was sponsored by — and unofficially named after — Assemblyman Byron Rumford, D-Berkeley, Northern California’s first Black legislator. There were only three Black legislators out of 120 at the time. There are now 12.

Scores of civil rights demonstrators occupied the Capitol’s second-floor rotunda between the two legislative chambers for weeks, a scene that couldn’t happen today due to tighter security — and hasn’t happened since. They slept on the tile floor at night and sang “We Shall Overcome” during the day, which irritated many lawmakers while also putting pressure on them.

Hugh Burns, a conservative Democrat from Fresno, attempted to prevent the bill from being voted on as the Legislature approached mandatory adjournment on the final night of its annual session. However, civil rights advocate Assembly Speaker Jesse “Big Daddy” Unruh of Inglewood threatened to kill all Senate bills pending in his chamber unless Burns released Rumford’s bill.

A compromise version was narrowly approved by the Senate at the eleventh hour, then breezed through the Assembly seven minutes before the midnight deadline.

But first, Unruh, the son of a Texas sharecropper who understood white racism, took to the Assembly floor to warn colleagues about the political dangers of getting too far ahead of the citizenry.

He was quickly proven correct. Proposition 14, launched by the California Real Estate Association, became one of the most emotional and vitriolic initiative campaigns in state history. There was never any doubt about the outcome.

The repeal was supported by the Los Angeles Times, which editorialized that housing discrimination was essentially a “basic property right.”

Pat Brown referred to the supporters of Proposition 14 as “shock troops of bigotry.” However, his vehement support for the Rumford Act contributed significantly to the governor’s reelection defeat in 1966. Ronald Reagan, a newcomer, easily defeated him.

Rumford was also defeated in a state Senate race.

Reagan drew voters in by promising to repeal the Rumford Act. But, once in office, he never tried. Give him that much credit.

The Rumford Act eventually evolved into today’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, which some Black legislators argue is not being adequately enforced, particularly laws prohibiting workplace and rental discrimination.

“The state agency is really understaffed and overburdened,” says Senator Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles). “Much of it has been gutted.”

“California proclaims to be the vanguard of progressive values and social justice, yet we have not invested in our civil rights infrastructure,” Smallwood-Cuevas says.

Yes. The bitter battle over the Rumford Act, on the other hand, reminds us of how far we’ve come in 60 years.

George Skelton is a columnist for the Los Angeles Times.